An Imperial Palace in Surrey

Editors’ Note: Today we present a blog post by Stephen Caffey, assistant professor in the Department of Architecture at Texas A&M University. One of our goals with Home Subjects is to explore the range of meanings that attached to displays of art in the context of the private house, a theme which Dr. Caffey explores below. Dr. Caffey will present a talk on this topic in the Home Subjects session at the Association of Art Historians conference in New York this coming February.

Easel paintings displayed in domestic interiors played an important role in the forging of modern Anglophone identities in the eighteenth century. The acquisition scheme and exhibition plan for Robert Lord Clive’s Claremont, near Esher, in Surrey, provides a case in point. Clive left England for India a man of little consequence and returned having amassed perhaps the largest fortune of any commoner in Europe. After having been elevated by George III to Baron Plassey, Clive undertook an audacious program of self-fashioning through art, architecture and landscape design. The intent of Clive’s pursuit was clear: to establish him as worthy of inclusion amongst England’s landed and titled elite.

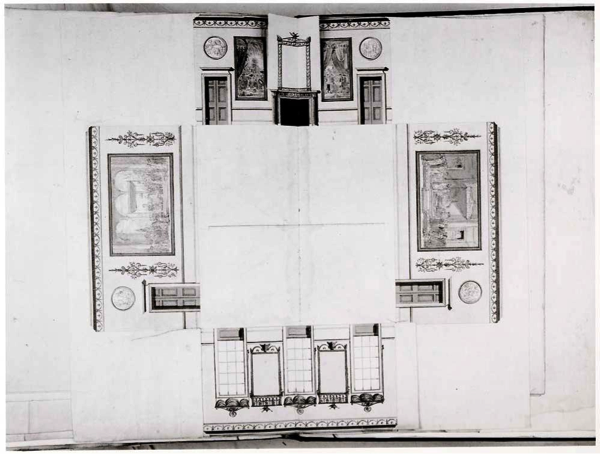

After having acquired the Claremont, Clive had the existing house razed and another constructed on a higher, less damp location on the site. Clive chose landscape architect Lancelot “Capability” Brown to design both the Palladian house and the surrounding vistas. Clive’s plans for the interior of the house included a Great Room, the walls of which would hold paintings by Claude-Joseph Vernet, Salvator Rosa, Claude Lorrain, Nicholas Poussin, Paolo Veronese and Jacopo Tintoretto—all acquired through two trips to Paris, one two Brussels, one to Rome and numerous visits to Christie’s London auction house. In order to mitigate the risks associated with his confessed ignorance of “the Value and Excellence of Pictures,” Clive entrusted the process to American-born history painter Benjamin West; scholar, connoisseur and Grand Tour cicerone William Patoun of Scotland; the English historian John Symonds; and the English art collector Sir James Wright. Clive charged the group with locating, authenticating, negotiating, purchasing and transporting the finest examples of European painting on the then very active art market and they in turn charged him, often exorbitantly, for their services.

The installation of the pictures at Claremont was designed to create the impression that generations of Clives had devoted themselves to the acquisition of fine European art, a conceit that flagrantly belied the fact that the entire collection had been amassed in just under five years. Having traversed the length of Claremont’s Great Room, guests would have passed through a door on the south wall to enter the Eating Room. With Veronese, Rosa and Poussin still fresh in their minds, viewers would have come upon Clive’s triumphal decorative program for the Eating Room, plans for which included four large-scale modern subject history paintings by Benjamin West, featuring highlights from Clive’s military and political career in India. Once fully complete, the Eating Room would allow patron, artist and viewer to fully explore—through easel paintings—the iconographic terms and conditions through which Clive wished to characterize his success. The initiative was all for naught, however: Clive may have conquered India, but he could not conquer English society. Unfortunately, West completed only one of the paintings, Lord Clive Receiving from the Great Mogul the Grant of the Duanney, before Clive committed suicide in November of 1774.

–Stephen Caffey