The Art Dealer as Decorator

Over the next few months, we will be exploring the interconnection of the art market and interior decoration in anticipation of the “Home Subjects” session at “Creating Markets, Collecting Art.” The blog will feature guest posts from the speakers on our session. This theme has a long history, and the practice of marketing art for the domestic interior still creates challenges for the decoration. Alexa Hampton, the designer and author of The Language of Interior Design once declared “art: beautiful to look at but tricky to hang,” especially in the home. Individuals, whether they consider themselves art collectors or not, have long worried about the best place to display a work of art in the domestic interior. And decorators have offered multiple solutions to the problem of where and how to hang art in the home. One question that emerges is whether the interior is planned around the art or the art selected to adorn the interior.

In A Strange Business: A Revolution in Art, Culture, and Commerce in 19th Century London, James Hamilton quotes a letter from Sir George Colebrooke, Bart., to his agent, Caleb Whitefoord that addresses this concern: “it may happen that something will be presented that will tempt you for me, either a large upright picture, to hang on one side of the Door of Entrance of the Drawing Room . . . or a long oblong picture or pictures with a view of hanging smaller pictures underneath to fill up the vacancy. The space between Door & wall is eight feet five Inches . . . I am disposed to lay out a sum between one & two hundred, either for one picture or more. (Letter dated 10 February 1805). Colebrooke had a long-standing interest in interior decoration, having commissioned a lavish new interior in 1771 from Robert Adam for his townhouse on Arlington Street. These designs were never realized, however, as Colebrooke faced financial difficulties due to speculative investments and the financial collapse of the East India Company, of which he was a director. He writes to Whitefoord, then, about decorating a new property after he had paid off his creditors by 1789.

The notion that a collector would look for a work of art based on how it will fit into his interior might seem anathema to us today. It seems odd to think of the “utility” of a work of art in this way, since the “usefulness” of an object would negate its status as art. Instead it becomes decoration. Public art museums, developed alongside Immanuel Kant’s theories of the disinterested work of art, promoted this idea by removing altarpieces, for example, from Christian churches and setting them apart for aesthetic contemplation rather than religious devotion. The “usefulness” of a painting, then, lies in its ability to address the needs of a specific consumer, in this case, one who needed a painting that would fit between a door and a wall.

From the vantage point of the early twentieth century, it appeared to the art critic Frank Rutter than the art dealer was, first and foremost, a decorator. As he noted in his memoir Since I was Twenty-Five, “with men like Sir Joseph Duveen, Asher Wertheimer, Charles Davis, etc., pictures are not much more than a side-line; they purchase and sell important pictures from time to time, but they also trade in a large variety of other works of art, decorative furniture, tapestries, porcelain, and all sorts of objets d’art.” Dealers like Duveen would set up apartments or devise mock domestic situations in which to invite clients to view works, it was unusual for the dealer himself to live on those premises as his home. Duveen decorated and stage-managed the firm’s outposts, including the window displays in high traffic locations such as London’s Oxford Street and New York’s Fifth Avenue. He combined the sale of paintings with tapestry, furniture, ceramics, and enamels.

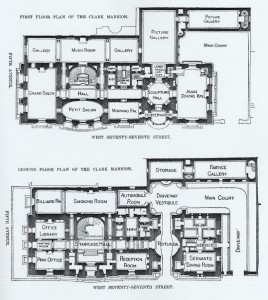

In one notable example, Joseph Duveen built a scale model of the new Fifth Avenue mansion of Senator William Clark of Montana, complete with a selection of art, carpets, tapestries, and furnishing that might look well in the new premises.