The Aesthetics and Ethics of Post-Impressionism in the British Home

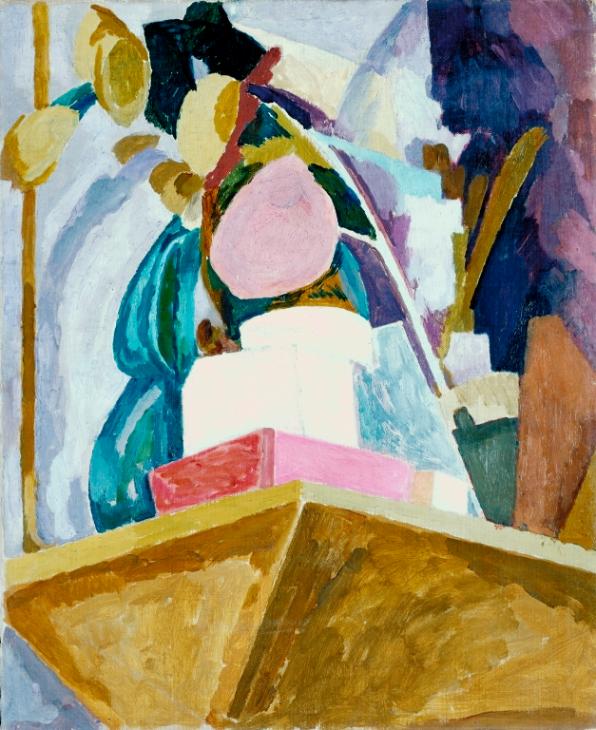

Vanessa Bell, Still-Life on the Corner of a Mantelpiece, c. 1914. Oil canvas, Tate. © Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett.

Editor’s note: Today we are continuing our series of posts previewing an upcoming Home Subjects panel at the conference Creating Markets, Collecting Art, which will convene at Christie’s Education in London July 14-15, 2016. Our next poster/speaker is Alexis Clark, who is Lecturer in Art History at the University of Southern California. –ANR

Written in the period that the Omega Workshops set up and then shut up shop (1913-1919), Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence (1919) details transformations in British home décor, from Arts and Crafts to the Omega Workshops’ Post-Impressionist-inspired aesthetics. “Mrs. Strickland,” Maugham wrote, “had moved with the times. Gone were the Morris papers and gone the severe cretonnes, gone were the Arundel prints that adorned the walls of her drawing room…; the room blazed in fantastic colour.” So, at the start of the novel, Mrs. Strickland, the female protagonist, resides in a den of Edwardianism, cluttered with overstuffed, heavily-carved, and otherwise festooned furniture. Not so much a sanctuary but a prison, her home symbolically suffocates her individual expression.

By the novel’s end, Strickland, who had come to own and operate a small press, redecorated her home to represent her newly redesigned life: with colorful, abstract, and geometric Post-Impressionist-inspired designs now enlivening the space. Such transformations in interior design were emblematic of the era’s wider calls for a women’s liberation that took the British home as the frontlines in that battle. Drawing connections between British domestic aesthetics and gender politics was a prominent theme in the Omegas’ designs and literature. The Workshops’ female and male artist-workers made Post-Impressionist-inspired interiors and clothes in an effort to create a modern domestic environment where gender equity could flourish.

Nina Hamnett and Winifred Gill, photographed in The Illustrated London Herald, October 24, 1915. The British Library.

Many women played an important part in the designs’ dissemination, from Vanessa Bell who designed housewares and fanciful clothes, to Winifred Gill who coordinated the Workshops’ day-to-day operation, to members of London’s upper crust (Lady Ottoline Morrell, Lady Cunard, Lady Drogheda and Lady Desborough) who all purchased items from there. Couture for the social set was not what the Workshops intended to produce—at least not at the outset. Bell had proposed that the Workshops take a sartorial turn in April 1915. Shortly thereafter, in June 1915, dresses, cloaks, and parasols, as well as Omega-printed and dyed fabrics, were put on display, to the warm reception of reviewers.

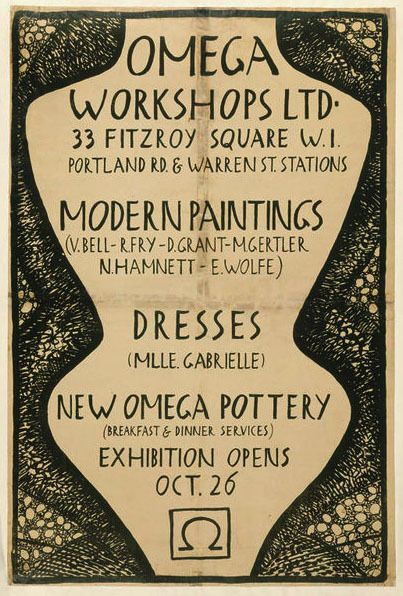

Roger Fry, Poster, c. 1918. Lithograph. Accession number E.738-1955 at the Victoria and Albert Museum

Dressmaking would sustain Omega through the First World War, leading the Workshops to advertise their foray into fashion. A lithographed poster for their October 1918 exhibit of paintings, dresses, and ceramics resembles the outline of a dressmaker’s mannequin, here slim-hipped and broad-shouldered. Loops and dots of ink emanating from the mannequin echo the stitches used to sew color-blocked, bold Omega dresses like those worn by Gill and Nina Hamnett in a 1915 photograph published in The Illustrated London Herald. As these designs, like those for the home, make evident, the Workshops endeavored to make a clean sweep of the Edwardianism that smothered both sexes’ (but especially women’s) individualism.

Omega’s advocacy of gender equity coincided with campaigns for women’s suffrage taking place on both sides of the Atlantic. Protests for women’s enfranchisement led the British Parliament to extend some women (those aged 30 or older who owned some property) the right to vote in November 1918, only months before Omega closed. Many Omegas, and those in their wider circle, sympathized with and participated in the suffrage movement. For example, in February 1907, the mother and sister of Lytton Strachey (friend and Cambridge schoolmate of Roger Fry and Clive Bell and eventual companion to many of the Omegas) walked in the so-called Mud March organized by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) under the leadership of Millicent Fawcett. And, in 1910, Fawcett, in her capacity as NUWSS President, supported a bill then before Parliament that would have extended political franchise to single and widowed women who headed their households. Lytton’s sister, Ray, who chronicled the suffrage movement, wrote the first biography of Fawcett. Much later, in 1938, she penned an article entitled “How to Build Your Own House” in which she asserted that her home, constructed by her own hand, rivaled that of any skilled architect or craftsman. Bell as well used her home as a site for critical discussions around “the equality of the sexes” and, like Ray Strachey, she painted and adorned her home at Charleston.

Photograph of Charleston House, decorated by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, c. 1916. © The Charleston Trust.

Thus, the home served as a site of contestation around women’s rights and one critical to the women connected to the Omega Workshops.

I explore Omega’s designs and advertisements, together with contemporaneous articles on British couture and home décor published in women’s magazines (Vogue and elsewhere) and on the ethics of domesticity circulated in feminist newspapers. Through these sources’ interwoven discourses, I contend that the threads of Omega’s designs (and their advertisements for them) were entangled, literally and metaphorically, in women’s liberation. As Maugham suggested in The Moon and Sixpence, the Workshops sold their Post-Impressionist-inspired designs while also more subtly selling a redesign of the home’s gender politics.