Trafalgar Day and a National Hero “at home”

Today’s post is written by Caroline Nelson, who completed her MA thesis titled “Richard Westall and The Life of Admiral Lord Nelson, 1806-1809″ at the Courtauld Institute of Art in the spring of 2015. She is currently Researcher and Assistant to the Executive Director at The Estate of David Smith in New York.

The issue of class and its role in the construction and subsequent study of the nineteenth-century domestic interior have been recurring themes on this forum. Today I hope to press the issue a little further. In honor of the 211th anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar on this “Trafalgar Day”, I offer you a brief look at the way in which one artist’s conception of a national hero made its way into the hearts – and homes – of a people at war.

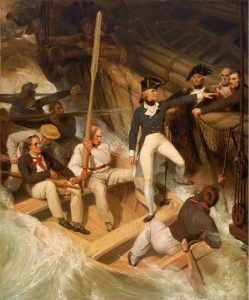

Richard Westall, Nelson boarding a captured ship, 20 November 1777, 1806. Oil on canvas, 86.36 x 71.12 cm. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/11913.html.

Last spring, I completed a dissertation at the Courtauld Institute on four paintings by British artist Richard Westall RA (1765-1836) depicting events within the career of Lord Admiral Horatio Nelson. Originally commissioned for reproduction in an extensive biography of the recently deceased naval officer, this series of works would be publically exhibited (1807), and each of its images respectively engraved and published (1808-1809), before the literary project itself was fulfilled (1809). I will admit that attempting to trace a handful of historical images through such a succession of artistic spaces was no easy task. Add to this the fact that the series centers around a man understood – both now and then – to exemplify the penultimate commander, and you can begin to imagine how quickly things got complicated. Somewhat fortuitously, however, Home Subjects provides an excellent framework for teasing out some of the most critical points of my argument.

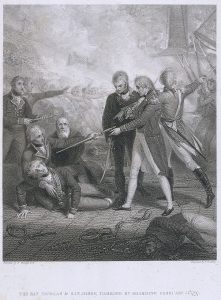

Richard Westall, Nelson receiving the surrender of the ‘San Nicolas’, 14 February 1797, 1806. Oil on canvas, 86.3 x 71.1 cm. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/14382.html.

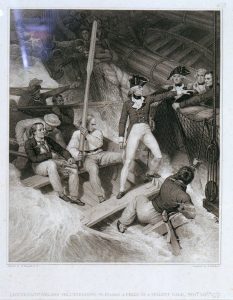

Richard Westall, Nelson in conflict with a Spanish launch, 3 July 1797, 1806. Oil on canvas, 86.3 x 71.1 cm. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/14381.html.

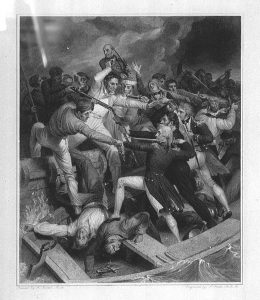

Richard Westall, Nelson wounded at Tenerife, 24 July 1797, 1806. Oil on canvas, 86.6 x 71.1 cm. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/11990.html.

Who were the viewers of these prints, and where were they displayed? In the context of the domestic interior, the answer is two-fold: they were the purchasers of mid-grade prints (available individually or as a bound set) as well as of lavish, leather-bound biographies.

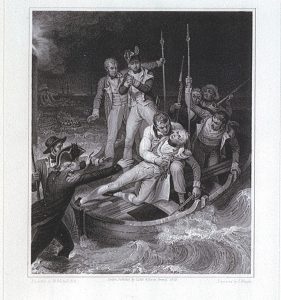

Abraham Raimbach, after a painting by Richard Westall, Lieutenant Nelson in the Lowestoffe’s Boat Volunteering to Board an American Letter of Marque Captured on the 20th of November, 1777, 4 June 1809 (published). Engraving, 51.6 x 40.2 cm. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/128768.html.

While there are many directions this information could, and should, be taken, I do not wish to overlook the obvious. In one of the inaugural posts on this site, Morna O’Neill warns of scholarship’s tendency to hone in on the private collections of upper class elites to the exclusion of all others; what’s more, she goes on to claim, is that even these spaces are all too often portrayed as fixed entities, immune to the constant flux of the outside world.

Richard Golding, after a painting by Richard Westall, The San Nicolas & San Josef, Carried by Boarding February 14th, 1797, 15 November 1808 (published). Engraving, 46.5 x 39.5 cm. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/109691.html.

In the case of Richard Westall and Horatio Nelson, falling into either of these traps could not be more regrettable. This is because in the case of Westall and Nelson, the researcher’s burden is eventually what becomes her fodder.

Whether hung on a wall or placed upon a stand, Westall’s series of works could be found in a range of households. And while they would have certainly affected a patriotic undertone as the war with France continued to drag on, I believe they must also be viewed as part of another ongoing narrative – one that both resulted from, and would continue to engage with, the very makeup of British society in the early 1800s. These illustrations highlight qualities viewers would have wished to celebrate, qualities of character and conviction that, without, their main subject might never have been celebrated in the first place.

Anker Smith, after a painting by Richard Westall, Rear Admiral Nelson’s Conflict in his Barge with a Spanish Launch, Night of July 3, 1799, May 1809 (published). Engraving and etching, 52.2 cm x 39.4 cm. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/108227.html.

By the time his body was laid to rest in St Paul’s Cathedral, Horatio Nelson had already become substantially mythologized in the public imagination through a plethora of visual, literary and even musical renderings. Westall’s set of pictures, and the way in which different subsections of society would have encountered them, effectively illustrate the complex yet far-reaching nature of the Nelson myth. While I am unable to delve into much detail about the events depicted, the significance their portrayal would have held for contemporaries can be understood (at least in part) without an extensive debriefing. Compositionally quite similar, the four vignettes show Nelson moving up in the ranks, engaging in behaviors that together create an image of both physical and mental perspicuity. Bravery in the face of brutal hand-to-hand combat as seen in the artist’s third image, for instance, is coupled with empathy and restraint for that same enemy in his second. What emerges from this version of Nelson’s exploits, then, is not just his martial prowess, but a model of behavior that viewers would admire and perhaps even wish to emulate.

John Neagle, after a painting by Richard Westall, Sir Horatio Nelson when wounded at Teneriffe, Night of July 24th, 1797, 1809 (published). Engraving and etching, 51.7 x 39 cm. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/128455.html.

In other words, just as Nelson’s admirable conduct facilitated triumphs in war (leading up to that which occurred on this day in 1805), so too did it facilitate triumphs in his own career and, ultimately, his reputation. So the myth that Westall perpetuated was truly not just for those able to afford a two-volume tome chronicling an entire life’s achievements; instead, it was a myth that a growing number of individuals would have had access to, literally as well as figuratively. By choosing to buy and display even one of the prints created after Westall’s paintings, Brits of more modest means were also buying and displaying a paradigm of duty, diligence, and the stature one could attain by employing them. Thus the Nelson myth was as much about its audience as it was about the man himself. A myth that would continue to be retold in dwellings across the United Kingdom long after he was gone.