Home (Subjects) for the Holidays: Queen Victoria’s Christmas

Over the next few weeks, we will be focusing our attention at Home Subjects on the way in which the display of art in the decorative interior intersects at this time of year with Christmas decorations, the history of this tradition, and what it might mean for the ways in which we encounter works of art in the home. Morna O’Neill and Anne Nellis Richter collaborated on this series.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert are usually credited with popularizing the German tradition of the Christmas tree in Britain, and in 2012, Windsor Castle recreated these and other decorations for visitors with the display “The Victorian Family Christmas.” (In fact, all one has to do is Google “Victorian Christmas” to realize the popularity of this concept. See, for example, the Christmas festival organized by English Heritage at Queen Victoria’s own Osborne House on the Isle of Wight). The installation at Windsor in 2012 was inspired by a series of images in the Royal Collection by artists and photographers that show Windsor Castle celebrating Christmas throughout her reign.

As the queen recalled in her diary on Christmas eve in 1850: “At a little after 6 we all assembled & my beloved Albert first took me to my tree & table, covered by such numberless gifts, really too much, too magnificent.” Albert’s generous gifts included a number of artworks: a watercolor by Corbould, paintings by Mrs. Richards and Thomas Horsley, four bronze statuettes, and a miniature of Princess Louise set within a bracelet designed by the Prince Consort himself. In fact, this and other visual evidence of royal residences during Christmas confirm what scholars have recently discussed: Prince Albert’s great interest in art and the important role that art collecting played in the royal relationship.

The oil painting by William Corden the Younger, based on a watercolor by James Roberts, draws on conventions for representing the royal interior in place as far back as the publication of William Henry Pyne’s The History of the Royal Residences in 1819. A massive undertaking produced over the course of four years, Pyne’s History depended on the full cooperation of the royal family. The very idea that the interiors of royal palaces should be illustrated, annotated, and otherwise made available to a general public was certainly an original one. The detailed illustrations, accompanied by a text explaining the history of the buildings and their contents sought to make the interior of the houses, with all their ancient history and contemporary splendor, accessible to a general reader.

The message Pyne’s views convey is that the interior spaces of royal houses, while in some sense transparent to the gaze of the public, remained securely private. The royal family’s decision to display the interiors of their properties to the British ‘public’ was a strategy to solidify their status as a private nuclear family and assert that their property belonged to them, rather than to the public. The interiors are certainly grand and not cozily homey, but they are clearly in use and occupied, a convention that the Roberts watercolor and the Corden copy follows. What we see here is the living space of a private family, complete with a view of their Christmas presents.

The watercolor suggests that the image of the Queen’s Christmas decorations and presents was meant to be circulated beyond the family and enter into a broader image culture not only of the royal family but also of the burgeoning traditions of Christmas decoration.

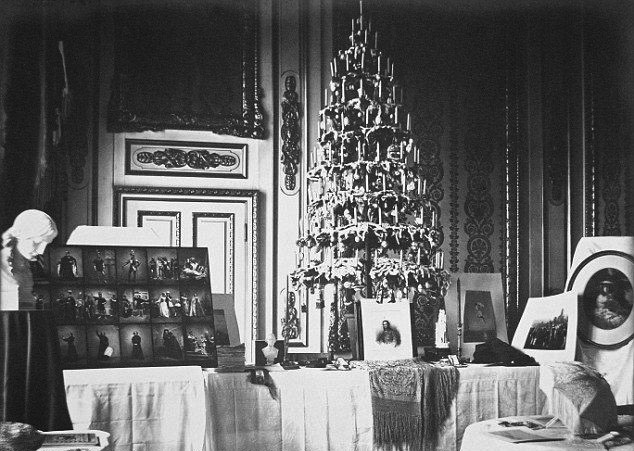

Other, seemingly more private, images were also produced: for example, Dr. Ernest Becker, who served as Prince Albert’s librarian, was also an amateur photographer and a founding member of the Photographic Society of London. He recorded the Queen’s tree at Windsor in 1857, which once again includes an impressive array of artwork as part of the gifts, including photographs, prints, and sculpture.

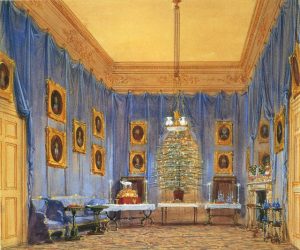

A second watercolor of a royal residence at Christmas, this one by Joseph Nash of the “Blue Closet” at Windsor Castle decorated with tree and presents in 1845, further suggests this co-mingling of public and private. We see the royal presents, including the magnificent silver and silver gilt “Atholl Inkstand,” designed by Prince Albert himself, to the left of the tree.

Atholl Inkstand, 1844-5, by Kitching & Abud for Charles Rawlings and William Summers. The Royal Collection.

As Queen Victoria wrote in her journal on December 24, 1845, “my presents were all arranged on a table. Amongst them was a most beautifully executed inkstand, with a stag in frosted silver, standing on Scotch stones, & at the sides views in silver base reliefs of Blair Castle & c. . . . Dearest Albert has so wonderfully thought out all his gifts.” The inkstand served as a memento of the royal visit to Scotland in September 1844, when they were lent Blair Castle in Perthshire by Lord and Lady Glenlyon. In the Nash watercolor, the stag seeks to stand at attention amidst an array of Victoria’s ancestors. Adorning the walls, hung with blue silk damask, are portraits painted by Gainsborough of the family of King George III. Victoria would later relocate these paintings to her private audience chamber by the 1890s. In this earlier moment, however, the paintings fully inhabit the role of family portraits. It is also an unwitting tribute to Queen Charlotte, who was said to be the first member of the royal family to bring yew trees inside for decoration at Christmas. Prince Albert selected fir trees for display, as was the tradition while he was growing up in Coburg, Germany.

As mentioned above, royal residences and other institutions continue to celebrate “Victorian Christmas” through decorations, and many art museums also participate in this tradition, even though that do not have associations with home. Perhaps art museums embrace the idea of Christmas decorations for this very reason: they make an institution seem more personal and, perhaps, homey, without unsettling the hierarchies in place. In our next post, we will explore some of the difficulties that can arise when public art museums attempt to incorporate holiday decorations into their displays.