Home (Subjects) for the Holidays: Decking the (Museum) Halls

Over the next few weeks, we will be focusing our attention at Home Subjects on the way in which the display of art in the decorative interior intersects at this time of year with Christmas decorations, the history of this tradition, and what it might mean for the ways in which we encounter works of art in the home. Morna O’Neill and Anne Nellis Richter collaborated on this series.

National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. at Christmas, 2005. Photo courtesy of National Gallery of Art/Rob Shelley

Now is the time of year when many institutions, from the shopping malls to the hospital, dust off their seasonal decorations, a category that might include everything from Santas to Christmas trees to menorahs and Kwanzaa candles. Museums are no exception, with many historic home museums and collections decorated for Christmas. At the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the gallery’s professional team of florists decorates with Christmas trees covered with white lights, pointsettias, and evergreens. Such seasonal festivity is not is not without controversy: as some commentators suggest, holiday decorations at museums can serve to re-inscribe dominant cultural models and limit the spirit of inclusiveness that museums should try to foster. Nevertheless, many institutions devoted to the display of art, especially historic homes, embrace the idea of holiday decorations, events, and themed tours.

Christmas Tree and Neopolitan Baroque Creche in front of Choir Screen from the Cathedral of Valladolid, Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Hanukkah Lamp, 1866-72. Polish, Lviv (also called Lvov or Lemberg). Silver: cast, chased, and engraved. On loan from The Moldovan Family Collection. Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York celebrates the winter holidays with the installation of its “Christmas Tree and Neapolitan Baroque Crèche” is installed in the Medieval Sculpture Hall. They also display an Eastern European Silver Menorah in the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Galleries.

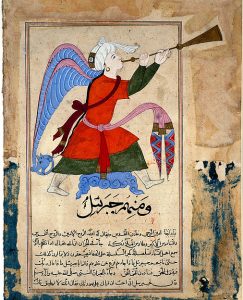

The Archangel Israfil, late 14th–early 15th century. Made in Egypt or Syria. Opaque watercolor and ink on paper. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

This year, the museum is presenting an exhibition titled Jerusalem 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven (on view through Jan. 8, 2017) devoted to the role the Holy City played in shaping the arts of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The objects in this exhibition represent a wide range of the visual arts, including a painted diptych, Jewish wedding ring, and an illuminated manuscript featuring the Archangel Israfil from late 14th-15th century Egypt or Syria. According to the exhibition website, the Archangel Israfil is a being named in the hadith, the sayings of the Prophet Muhammed. When timed to coincide with the winter holiday season, such temporary exhibitions may serve to make the museum feel more inclusive to a wide range of patrons and educate audiences about the extremely complex visual culture of religion.

The Christmas Tree and Neopolitan Baroque Crèche, however, are a longstanding tradition at the museum, which first presented this display in 1957. It is an unusual combination of Southern European (crèche) and Northern European (tree) traditions, the brainchild of Mrs. Loretta Linn Howards, who began collecting the nativity pieces in the 1920s.

One would imagine that the crèche figures would inhabit a very different display context if they were to be integrated with the presentation of eighteenth-century art upstairs at the museum. Would the figurines be considered worthy of display at the museum if they were not associated with holiday decorations? A recent rule put in place by the museum suggested that they would be: Despite protests from the Howards family, who had traditionally participated in the arrangement of the display, the figures would be handled by Met staff only. The family’s hurt feelings seem to suggest that even when it comes to the display of art, the celebration of the holiday remains within the province of private feeling. Although the donors have given the figurines to a public institution, the act of placing them in front of the tree, hanging the ornaments, and otherwise arranging the ensemble remained a family tradition. This type of display blurs the boundaries between decorative object (in this case, personal possessions with emotional significance) and museum object in a way that paintings and sculptures do not always do.

It seems significant that this tradition at the Met started in the 1950s, a cultural moment that celebrated the nuclear family as the foundation of society. As Stephanie Coontz points out in her study The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap (1993), the family focus of the holiday celebration developed in the twentieth century. Historically, she notes, Christmas “seems to have been more a time for attending parties and dances than for celebrating family solidarity.” Does the practice of decorating of museums and historic interiors for Christmas invite us to psychologically displace 20th century attitudes onto past eras? In addition, Coontz describes how the upper-middle class lifestyle that is idealized as the standard “family” of yesteryear was only permitted by unseen working class labor, usually by immigrants and people of color. When the museum adopts the decorating practices of a specific type of upper class American, like those of the Howard family, they may appear to codify these traditions without also appropriately documenting and historicizing them. Of course, holiday decorations and traditions associated with most religions are not fixed but highly mutable in response to the general culture and developments in technology, personal preference, and of course the pressures placed by family dynamics.

Christmas tree at Reynolda House in Winston-Salem, N.C. Photo courtesy of Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

Yet, despite these possible objections to the practice of decorating museums for the holidays, foregoing them does not seem either practical or desirable. Holiday decorations provide festive atmosphere and draw people into institutions they may not visit at other times. They permit museums and galleries to present a friendlier aspect, particularly to constituencies like children–many examples of holiday programming at museums involve activities for children. But since holiday decorations (at least in Western traditions) are typically most associated with domestic dwellings, perhaps house museums provide the ideal space in which to celebrate the joyous cultural traditions that decorations represent while also historicizing their meanings. In the final post in this series, we will look at a few institutions that are attempting exactly this–embracing Christmas as a holiday meaningful to many of their patrons while placing specific types of decorations and traditions within an appropriate historical frame.