Domesticity and the Everyday in Eighteenth-century Paris

Editor’s note: Today we present the first in a series of posts previewing an upcoming Home Subjects panel “Art and/in the Private House” at the annual meeting of the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies in Minneapolis, Minnesota, March 30-April 2 2017. Our first poster/speaker is Kristin O’Rourke, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Art History at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. –ANR

Life at the court of Versailles was characterized by formalized rituals and hierarchies; it was a place where life was lived in public and bodies were strictly policed by etiquette. Louis XIV’s insistence on social control resulted in an increasingly stiff, uncomfortable bodily existence for his courtiers, circumstances that were revealed through dress and furniture. In reaction, the younger generations of the royal family promoted an informal and more private counter-existence to their role at court, and by the early decades of the 18th century even Versailles boasted of everything from flush toilets to cozy Turkish beds. As the aristocracy drifted away from the court during the Regency and reign of Louis XV, the city of Paris offered a freer and less restricted social existence. In the capital city, the elite renovated their dwellings and spurred a building boom; a sea of architects, designers, craftsmen, artisans, and artists went to work updating, expanding and building hôtels particuliers, the private, often free-standing elite residences occupied by the upper classes. As Joan DeJean has argued, it is at this moment that life became comfortable, rather than just grand; our modern-day associations of comfort with luxury clearly stem from this shift. In contrast to the publicness of court life, the new emphasis on privacy allowed a space for emotions to be expressed. While we often associate Rococo private life with libertinism and erotic activity, the private space became also the location of the nuclear family.

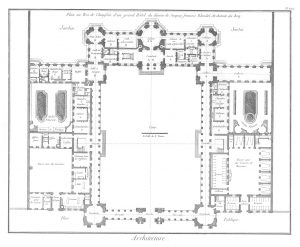

These hôtels offered refuge from the stifling surveillance of communal living at court and served as oases from the dense urban environment in which they were built. Known by surviving structures as well as by published plans, the hôtels were walled off from the city by large gates and sculpted courtyards, and contained everything needed for the household from kitchen garden to stables to entertaining and familial spaces. The Hôtel de Soubise (now the home of the National Archives) was created when much older residences were combined and renovated to create what is seen as a gem of Rococo adaptive design; when one enters through the doorway from the busy street into the main courtyard, a sanctuary reveals itself. The hôtels were constructed and redesigned on a scale more human than the gargantuan royal palace of Versailles. Rooms were smaller and differently-shaped, some were quite intimate. Characteristic of these homes is the wide variety of purpose-built rooms, allocated for eating, bathing, sleeping, entertaining, and so forth. Additionally, the diminution and later elimination of the “parade” suite and public bedroom meant that as the century progressed most creaturely activities took place in private.

Plan of the ideal hotel, from the Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, ed. Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, 1751-1772.

As the wealthy sought comfort and convenience in their homes away from court, architects and designers exploited innovative technology and craftsmanship to satisfy their demands; mechanical writing tables, built-in storage, indoor plumbing, private staircases, and comfortable, casual furniture types were developed and then published, advertised, and extolled to the larger public. The painter François Boucher was frequently commissioned to decorate these homes with mythological or pastoral scenes that fit into shaped openings over doors, on panels, and in traditional frames.

If we correlate the architectural record with painted representations from mid-century, we can understand how these new spaces were employed. The rapid pace of the shift from a fully public to a semi-private life reflected in built form is reproduced in genre scenes and portraits from these middle decades. Genre scenes by François Boucher and portraits by François-Hubert Drouais bring us, phenomenologically speaking, into the day-to-day world of elite urban dwellers just described. The interior room of a contemporary elite dwelling is the mise-en-scène allowing the family affect to come into being. Everyday family interactions are encased and showcased in these fashionably decorated yet intimate domestic spaces. Affluent urban families who spent their wealth on furnishings, interior décor, and beautiful clothing, both real (in portraits) and realistic (in genre scenes), expose and indulge their feelings without fear of ridicule or reprisal; the warm and attentive relationship of parent to child and between couples within the nuclear family visualizes an experience of natural emotions not always discussed in regard to Rococo art of the ancien régime.

Boucher’s genre scenes do not stray far from the gilded world of the private hôtel, but his focus shifts in these works to representing everyday life within the walls of those very homes. His paintings entitled Family Taking Breakfast (1739) and The Milliner (Morning) 1746 (illustrated above), suggest the lived experience of the elite and demonstrate an increasing emphasis on emotion and family life within the private, domestic sphere. Over the years Family Taking Breakfast has been interpreted as a Boucher family portrait, although it is more likely a generic family at breakfast being served coffee by a servant (and not by M. Boucher himself). The morning meal and the fashionable drinking of coffee take place at ease and in private. The attention of the mother, who is wrapped up in a short, red fur-lined cloak, is drawn away by her child; she looks over her left shoulder at the child and simply watches and listens to the little girl, who grasps her dolls and toys. The attitudes and manners of the adult figures are refined and elegant, even that of the servant (hence the confusion over his status); there are no melodramatic gestures or overt posing. The nuanced realism of the mother’s body language and her bemused, patient facial expression is familiar to anyone who has attempted to eat breakfast while being interrupted by his or her young child. The figures in Boucher’s genre scenes are generalized and idealized – they are young, attractive, and self-contained, less demonstrative than the artist’s contemporaneous mythological images, and lacking also their explicit eroticism. Although nonspecific, the bodies and their interactions in the genre scenes feel genuine.

François-Hubert Drouais, Family Portrait, 1756, oil on canvas, Samuel H. Kress Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Similarly, mid-eighteenth century portraiture may reveal the willingness of this class to put family relations and emotion on public view. François Drouais’ 1756 portrait of an unnamed family (signed on the blue and white cardboard box, in homage perhaps to his former teacher’s playful signature on The Milliner of 1746), represents an inner room where the nuclear family can form and bolster their emotional bonds in private – in this case within the mother’s bedroom. We see the mother at her toilette table, surrounded by her daughter and husband. The daughter presents her with an overflowing basket of flowers, which echo the artificial flowers being put in her own hair by the mother and the other trimmings (ribbons, pearls, gold flowers) we see spilling out of the box on the floor. On the other side is the husband who leans casually and companionably on the back of his wife’s chair. He bends into her while looking lovingly at their young daughter, who is in many ways a miniature version of her mother. The mother’s toilette is soft and natural: her hair is lightly powdered, and she wears minimal rouge. The daughter, although it appears that her hair has been dressed and powdered, does not yet wear makeup and her free movement despite the corseted dress indicates a body that is allowed to move and play. The accessories on the toilette table are deemphasized, as if the table and the grooming ritual are a location and a daily event rather than end in and of itself. The emphasis is placed instead on the emotional connections of the family group, the roughly pyramidal shape of affect where each figure flows into the other to create a harmonious and stable domestic unit, exuding contentment.

Over the next few decades, sentimentalizing rustic narratives-such as those painted by Jean-Baptiste Greuze–grew more prominent and were praised by critics like Diderot for their overt emotional content. In contrast, these mid-eighteenth century Parisian works denote a world that is both historically and geographically specific, and emotionally real. Allowed behind closed doors to practice and express familial devotion, the urban elite then visualized those feelings through portrait commissions and the patronage of genre scenes, works that reveal an opening in the public façade and offer a glimpse into the domestic world of the old regime.