Art and/in the Interior: Reflections on ASECS 2017

Last month the Home Subjects team convened a panel at the 48th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies. This panel, organized by Anne Nellis Richter and Melinda McCurdy, brought together four stimulating papers highlighting new research on the display of art and objects in the domestic interior. Links to previously-posted synopses of these talks may be found below by clicking on the name of each author. The purpose of this post is to share some of the insights and ideas that emerged from the stimulating conversation that followed the talks, and in a few cases suggest possible future avenues for discussion.

On the surface, the array of topics seemed diverse enough that the papers might find little common ground. However, when presented as a group it became clear that each paper highlighted a methodological approach that tied back into one of the major themes of Home Subjects. From the beginning we at Home Subjects have been interested in drawing out the interconnectedness of objects and the interior spaces they decorate. The topic “Art and/in the Interior” may at first conjure visions of easel paintings and how they are displayed on the walls of a private house.

However, paintings form but one layer of the decorative palimpsest of the private house. Easel paintings (or two-dimensional artworks more broadly) are exhibited in private houses according to their own particular logic and conventions, but they are displayed in concert with furniture, carpets, window coverings, wall coverings, lighting, and the many smaller objects that served both useful and decorative purposes. This decorative context is one of the ways in which display in private spaces can be distinguished from display in public places over the course of the eighteenth century. Three of the four talks expressly touched on the experiential aspects of looking at art in the interior, including subjects like the movement of the body through space and the introduction of multi-sensory elements into the experience of artwork, in particular scent and sound. All of the talks, in different ways, worked toward illuminating the major theme of Home Subjects, which is to understand the development of art in the private house over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As purpose-built spaces for the display of art became increasingly wide-spread over the course of the nineteenth century, they often announced themselves as “public” by removing many of the comfortable trappings of the private interior. Moreover, just as the display of art in public spaces may illuminate the behavior expected of visitors (for example, at the Royal Academy exhibitions small pictures were hung low to encourage close inspection) several of these papers pointed to what the arrangement of objects in the private interior may tell us about how viewers interacted with objects and with each other.

Kristin O’Rourke discussed the development of the family portrait as a kind of domestic genre scene in the context of early eighteenth century Parisian houses and interiors. At this stage it is too soon to say much about where in the house these pictures were displayed, and how frequently they appeared in public venues such as the Salon. From a methodological standpoint, those of us studying interiors require many layers of evidence to be able to fully understand these issues, including family archives, inventories, house plans, and ideally letters or diaries reflecting what people thought about these pictures to be able to begin to understand why they look as they do and how they functioned in the context of the private house. One subset of these scenes show women in a state of undress, posed at their toilette tables which are in turn laden with the decorative and useful objects with which private interiors were outfitted.

Sir Peter Lely, 1618–1680, Dutch, active in Britain (from 1643), Diana Kirke, later Countess of Oxford, ca. 1665, Oil on canvas, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

While as of now we have little evidence to show where in the house such portraits were displayed and who would have had access to them, a potentially fruitful course for further research, the very fact that the subjects were sometimes only partially dressed might lead us to expect that they were exhibited in the more intimate rooms of the house. For insight we might look to a similar example, the court beauties of Charles II painted in a similar state who were frequently painted in a similar state. As Julia Marciari-Alexander has suggested, these pictures appeared in spaces that would have been accessible to select members of the court, visualizing the intimacy these ladies enjoyed with their King.

One of a pair of potpourri vases “à dauphins” (in the form of a dolphin). Soft-paste porcelain, 1755. Manufacture de Vincennes and Sèvres, Louvre OA11300.

Hyejin Lee’s talk about the function and decorative role of potpourri containers in the eighteenth-century house prompted a different set of methodological reflections. Lee’s interest in these incredible objects was prompted by the frequency with which they appeared in museum displays of eighteenth-century decorative arts. Their ubiquity in the eighteenth century interior seemed to stand in inverse proportion to the amount of information presented to the twenty-first century museum visitor, as these objects were often displayed in white, sterile museum cases with no explanation as to their original function or context. As Lee’s talk demonstrated, when first made, these vessels were the point from which the household could be perfumed with a dizzying array of scents, many of which were designed to treat specific medical disorders, all of which were source of pleasant scent in the private interior intended to ward off the unpleasant and sometimes dangerous smells emanating from the public space of Paris just outside. To fully appreciate and understand these objects, their sensory purpose should be evoked, even in the context of the museum.

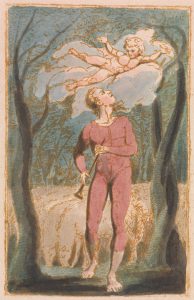

Print made by William Blake, 1757–1827, British, Songs of Innocence, Plate 1, Frontispiece (Bentley 2), 1789, Relief etching printed in brown with pen and black ink and watercolor on moderately thick, slightly textured, cream wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Craig Stamm’s talk on how William Blake used the space of the middling-class salon of Harriet Mathew to shape his artistic persona delighted our audience by conjuring the vision of Blake singing to his assembled admirers. Using evidence drawn from first-person accounts of these gatherings, Stamm is able to partially illuminate what went on in Mathew’s house in concert with the display of artworks and reading of poetry. As Stamm noted, evidence of Blake singing and that the Salons were frequented by music professors tantalizingly suggests the extent to which music and art were mingled in a space that may have been widely interdisciplinary. However, again Stamm’s project points to the methodological challenges posed by such projects, as a range of sources is needed to begin to fully understand both Blake’s part in the Salon and how various participants may have understood this space and the art and music presented there. At the same time, it encourages us to think about how music informed Blake’s vision and artistic practice, both literally and metaphorically.

Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, Triumph of Caesar, c. 1713. Kimbolton Castle (now Kimbolton School), Kimbolton, Huntingdon. Photo credit: Laurel O. Peterson

Finally, Laurel Peterson’s talk on Pellegrini’s murals in the staircase at Kimbolton Castle pointed to one avenue art historians may take to address some of the methodological obstacles mentioned above. In the face of a lack of written documentation showing how patrons or visitors might have encountered or understood decorative paintings in the private house art historians carefully read the pictures themselves, using formal analysis in conjunction with archival research, as visual evidence. In Peterson’s talk, for example, she reconstructed the manner in which a viewer might walk up the stairs and the physical process of viewing the pictures to help her unravel their sources and possible meanings. Another fruitful line of enquiry is the interrelationship of the mural painting and the decorative objects that filled the interior of the house–Peterson evoked the ways that objects in the painting–silver ewer and gilded throne, for example–should be understood as in dialogue the decorative arts that surrounded them.

We look forward to further investigation of these and related topics and ongoing discussion of the interrelationship between the display of art and all of the elements making up interiors of private houses.