“Bizarre Arrangements:” Framing Rococo Painting

It must be said, again, that painters almost never work for themselves […] Currently, we poor modern artists are reduced to painting over-doors, the only place where our talents can shine; a dishonorable place, yet one in which we are expected to give birth to beautiful ideas […] Since I returned to Paris this is all that I have been asked to do. Then consider the bizarre formats, the wall colors that are not always appropriate for paintings, in a word a thousand disadvantages. This is what we have to put up with, for our work is no longer seen as painting, but rather as a sort of furnishing that must fit in with all of the apartment’s bizarre arrangements.

-Charles-Joseph Natoire to Antoine Duchesne, 7 April 1747

Figure 1. François Boucher, Astronomy, 1745. Cabinet des médailles, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

This post describes in broad strokes research conducted on an ubiquitous yet almost entirely uninterrogated picture format: irregularly shaped canvases known as chantourné (“cut-out”) that were intended for insertion into the paneled interiors of eighteenth-century France (fig. 1). Produced frequently by the 1720s, by the 1740s they constituted a sizeable part of key academic painters’ employment, notably that of François Boucher, Charles-Joseph Natoire and Jacques de Lajoüe. As preparatory drawings indicate (fig. 2), painters almost invariably responded to architects’ and woodworkers’ wall elevations, rendering the artist’s task one worthy of Natoire’s lament and, later, Charles-Nicolas Cochin’s parodic praise in the Mercure de France (1755):

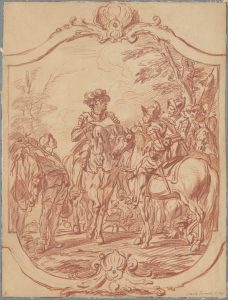

Figure 2. Joseph Parrocel, Scene of military life: A general giving orders, 1744, for the apartments of the Dauphin, Versailles, red chalk, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

“But where our genius triumphs is in the frames of over-door paintings, for which we can claim we have provided an infinity of different designs. Painters hate us because they do not know how to arrange their compositions with the encroachment of our ornaments on their canvas; but too bad for them: such a great display of genius should stimulate their creativity; these are the kinds of bouts-rimés that we give them to fill in.”

“Bouts-rimés” were games in which a list of rhyming words was supplied for which verses were to be “filled in” (“à remplir”). The spatial arrangement of the form – either blanks with a list of words aligned at the right, or the inverse, verses terminating in blank spaces – would have been very familiar to readers of the Mercure which had held “Bouts-rimés à remplir” competitions regularly in its pages since in the 1720s.

In many cases, however, chantourné paintings’ original housing in custom-made surrounds was quickly abandoned – within years of installation, or over the course of the nineteenth century, when the artists’ names associated with painted portions called these works out into the art market in order to function (more or less convincingly) as independent easel paintings (fig. 3). Almost invariably, then, along the way paintings with color ranges and, above all, compositions that anticipated highly particular homes were either built out (often through relining) or cut down in order to achieve more familiar formats that dealers, collectors and, eventually, museum gallery visitors associated with “Art.” Curiously, then, while the paintings survive in significant numbers and are regularly discussed as key moments of the French rococo, in material history terms they are often much modified in ways that scholars have failed to address. Original formats and modifications are listed in conservation notes as if these were incidental condition issues rather than foundational to the very way the painting took shape. Indeed, in most instances, reconstructing the original surround even approximately through an overlay or matting dramatically restores the compositions of these paintings into more satisfying, less visually scattered and coherent arrangements.

Figure 3. François Boucher, The Interrupted Sleep, 1750, for the château de Bellevue, showing alteration into a rectangular format. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Boucher’s The Interrupted Sleep as framed on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, from http://www.ipernity.com/doc/laurieannie/24723757/in/keyword/294426/self.

Why has the chantourné condition of many eighteenth-century paintings been largely ignored? Most broadly, we might propose that their at-homeness in private interiors was, in a sense, directly hostile to art’s newfound publicness and Salon culture. In a survey of the Salon guides (livrets), the term “chantourné” appears for the first time in 1738 but is not used after 1750. Such decontextualized paintings with irregular formats must, indeed, have appeared as increasingly strange interlopers at the Salon and a challenge to the unified display of the French school. Moreover, there is much evidence to suggest that the term itself coded these works among the mechanical rather than liberal arts. In his review of the Salon of 1746, La Font de Saint-Yenne described Boucher’s Eloquence and Astronomy (fig. 1) for the king’s recently completed Cabinet des Médailles as “two paintings for over-doors of figured shape [‘de forme figuré’] that workmen improperly call chantourné.” La Font presumably responded to the description offered by the livret, where they appear listed as “chantourné.” His concern is both accurate and revealing of the tension surrounding painting’s uncertain status at this moment. Prior to the first definition explicitly to link paintings with “chantourné” (made by Denis Diderot in 1753), the word was defined either in technical woodworking terms or in order to describe ephemeral cut-out festival and funerary trappings of the kind associated with the Menu plaisirs du roi. Its link to paintings was evidently tangential or comparative. It was probably first used by the woodworkers engaged in making the complicated stretchers that were typical of the most costly examples and ensured the snugness of fit between painting and wood paneling.

Figure 5. Jean-François de Troy, The Declaration of Love, c.1724, The Wrightsman Collection, New York.

Jean-François de Troy’s The Declaration of Love (c.1724) suggests that the chantourné’s symbolic function for describing particular milieux in the wake of Louis XIV was solidified remarkably early on (fig.4); undoubtedly, it continued to serve this function in genre scenes well into the 1740s, as discussed by Kristen O’Rourke in a recent post. And, despite the often radical reframing of many chantourné canvases that normalized them into rectilinear formats, the phenomenon of the irregular shape had tremendous influence and longevity as a sign of French rococo decoration.

Figure 4. Michael Hoppenhaupt II and Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff, Music Room, Sanssouci, Potsdam, 1747.

Around 1747, for the Francophile Frederick the Great, Johann Michael Hoppenhaupt II and Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff took the form to an extreme never adopted in Paris for the walls of the music room at Sansoucci (fig. 5). The Lafrancini Brothers’ rocaille plaster surrounds for four oval seascapes by Claude-Joseph Vernet in the dining room of Russborough House seem to be linked to the national origin of the canvases, albeit dating from later than would have been commissioned in France. By the nineteenth century, shaped canvases were standard signs used in the most important rococo revival interiors, including Wrest Park (1830s) or Mentmore Towers (1850s, with paneling taken from the hôtel de Villars, 1732-1733) and, across the Atlantic, at the Astor family’s Beechwood in Newport, Rhode Island (1851).

An in-depth presentation of this research, particularly from etymological and historiographic points of view, is forthcoming.