Domesticity and Orpen’s “Homage to Manet”

Orpen, William; Homage to Manet; Manchester Art Gallery; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/homage-to-manet-205754

In 1909, the Irish artist William Orpen commemorated a gathering of friends with this painting, entitled Homage to Manet. Six men sit or stand around a table ready for tea, posed beneath a painting by the French Impressionist artist Edouard Manet, his portrait of his student Eva Gonzalès, from 1870. The group includes Orpen’s fellow artists Philip Wilson Steer, seated at the table below the painting, and Walter Sickert, standing off to the right, fingering his labels as he listens. Both traveled to France in the 1880s. There, the first-hand encounter with Impressionism influenced the direction of their art. They are joined by what we might call educators: the artist and influential art teacher Henry Tonks, the art critic and curator D. S. MacColl, and the Irish novelist and art critic George Moore. Each played a vital role in educating artists and the public about recent developments in modern art. Here they do not talk, nor do they pore over a shared text; rather, they listen. MacColl’s gaze is intent upon Moore, while Tonks pulls taut a red length of ribbon as he loops it around the index finger of his right hand; perhaps this is the ribbon that held together the print portfolio behind him. Moore reads from his Reminiscences of Impressionist Painters (1906), which recounted his youthful friendships in Paris, especially with Manet, whom he praised as “the eye that sees clearly and quickly.” The tilt of his head suggests that he is addressing his remarks to Manet’s painting. Yet the one who listens most intently, hand to his head in concentration, is the one who made this homage possible: the art dealer, collector, and philanthropist Hugh Lane. He purchased the painting in 1906 from the Parisian art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel and loaned it to Orpen to hang in his studio.

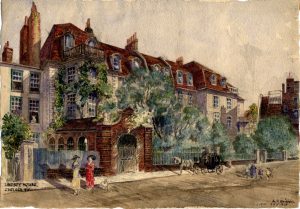

Alfred Francis Griffen, Lindsey House, Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, c. 1920, watercolor, Local Studies, RBKC.

Homage to Manet stages the act of connoisseurship within a domestic setting: Manet’s painting presides over comfortably upholstered furnishings, a casually discarded hat and gloves, and the table set for tea. While Orpen’s painting shows Eva Gonzales hanging in his studio, Hugh Lane likewise used the domestic sphere to position himself in the Edwardian art world in relation to artistic domesticity. In 1909, he purchased Lindsey House, a historic property in Cheyne Walk, where he was to create a showstopping interior to display his dealer stock, a house that also served as his dwelling. Lane differentiated himself from his fellow dealers by styling himself as an aesthete and a collector. According to his friend and biographer Thomas Bodkin, Lane was a skilled decorator, and Lindsey House became his show piece.

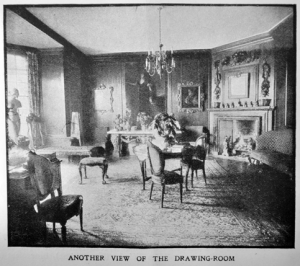

The interior decoration garnered illustrated profiles in The Sketch, The World, and The Graphic. His decision to hire his friend Edwin Lutyens, who was just then gaining fame as a noted architect, to re-design the back garden generated further press. Lane commissioned three large scenes of gypsy life for his front hallway from the artist Augustus John, a powerful declaration of his role as patron of modern art. Upstairs, however, he orchestrated a celebration of aristocratic taste, outfitting the spectacular double drawing room on the first-floor with Jacobean-style oak panelling, providing a backdrop for his collection of Chinese and Japanese ceramics as well as the Old Master paintings available for purchase in his dealer holdings. Lane’s friend, the architect J. M. Solomon, recalled that Lindsay House evoked a range of artistic references: the most important rooms faced south, and the bay windows overlooked the Thames in a way that suggested James Abbot McNeil Whistler’s nocturnes while the light in the room mirrored the art of Rembrandt and Goya that hung on the walls. In turn, Lane himself seemed “in appearance similar to the figures in the paintings of that strange seer, El Greco.” Perhaps Solomon saw the resemblance between Lane and the ecstatic yet emaciated body of Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata (1590-95; National Gallery of Ireland) that entered Lane’s collection sometime before 1913.

The domesticity of Lindsey House was vital to Lane’s reputation because he lived with his art. Recent scholarship has turned to the domestic interior as a generative site for cultural meaning, addressing the ways in which the decoration of the private interior was a means of formulating the public self. Lane himself, via the interiors at Lindsey House, seemed to embody the ideal of aesthetic domesticity: he lived for, and with, art. According to Lady Gregory, Lane acquired Lindsey House for his pictures, “for he liked to have them around him, and he never put them in a shop or showroom away from his own abode.” In his primer for collectors, Lane’s friend C. J. Holmes recommended living with art as more important for the formation of taste than museum visits: “the best training for the eye is habit, and habit cannot be wholly acquired in museums or galleries. The stimulus of possession makes one examine more closely, consider more lengthily and compare more carefully.” By setting up his business in his home and operating as a finder and supplier, Lane opposed himself to the world of the commercial art gallery and the professional dealer, who, it seemed, cared more about his bottom line than the works of art currently in his possession. In this formulation, possession is commensurate with knowledge, and Lane’s close, daily engagement with art enhanced his status as an expert.

An air of easy familiarity with masterpieces is evident in Orpen’s Homage to Manet. Eva Gonzalès and her admirers suggest the way in which paintings and interiors could work together in cosy domesticity. One key aspect of Lane’s life at Lindsey House was the daily encounter with great works of art, an experience evoked by Orpen’s Homage. A breathless profile of Lane in The Sketch in 1915 elided the man with his home in order to express the extent to which they were interdependent: “But you must know Lindsey House and its owner—the richness of the one and the quiet enthusiasm of the other—to appreciate the content that comes on a man who makes collecting an art and dealing a mission.” Orpen doesn’t just describe the drawing room—he envisions it as a space of encounter. Take, for example, the presence of a copy of the famous Medici Venus, a Hellenistic statue of the goddess of love and beauty in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. In Orpen’s painting, the statue suggests shared ideals of art and beauty among those gathered around the table. In this drawing room, Venus and Eva look at one another, as if in acknowledgement of Charles Baudelaire’s dictum from his seminal essay “The Painter of Modern Life,” published in 1863: “Beauty is made up of an eternal, invariable element, and of a relative, circumstantial element.” It was Lane who enabled this exploration of beauty as a dialogue between the past and the present, as he owned both the painting and the statuette. While he sent the canvas to Dublin for the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art (today it is shared by that institution, now known at the Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane and the National Gallery in London), and he placed the Venus in the drawing room of Lindsey House, near the bay window overlooking the Thames. There, its associations with art and beauty continued, and perhaps its evocation of Medici patronage and collecting were not unwelcome.