The McCullough Collection of Modern Art at 184 Queens Gate, London

‘Interior at 184, Queen’s Gate’, http://123-mcc.com/other_history_art_journal.htm#Interior_at_184_Queens_Gate_London. All views taken from this site.

Update: we’ve recently learned that a new book on the McCullough Collection was published in New Zealand. For more information, contact the author Lawrence Robert McCallum through this link.

The most recent issue of the journal 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century addresses “Technologies of Fire in Nineteenth-Century British Culture.” The essays explore “fire as a visual and narrative technology in art, literature, and public displays by examining the ways in which fire evoked competing symbolic values, such as primitivism and modernity, vitality and destruction, intimacy and spectacle.” The notice of this issue arrived in the Home Subjects inbox around the same time as news alerts about the closure of the Getty Center in Los Angeles due to the threatening Skirball fire, burning “directly across the freeway” from the Getty. The museum has reassured the public that the buildings and art collection are not at risk, but it got us wondering: What sorts of precautions were in place to protect art collections from fire in the nineteenth century? We’d love to hear about any current research on this topic.

While none of the fascinating articles in the “Fire” special issue addresses this question, one of the articles does contain fascinating images of the display of art in the domestic interior: Nancy Rose Marshall’s essay “Victorian Imag(in)ing of the Pagan Pyre: Frank Dicksee’s Funeral of a Viking.” She weaves a fascinating discussion of the late Victorian painting of the title around the cremation movement of the late 19th century “in order to glimpse the work performed by the visualization of the ritualized burning of human beings in the pagan past.” As Marshall points out, “given its imposing size, sensational subject, and dramatic lighting, the picture was clearly intended to make a statement.” The artist considered it his “most important” work to date.

It was commissioned from Dicksee by George McCullough for his collection of British art, begun in 1893. McCullough (1848-1907) made his fortune in mining, establishing Broken Hill Mining Company (it trades today at BHP). After a failed attempt at shipbuilding, he traveled to Australia to try his hand at sheep farming. He was working at the Mount Gipps Sheep Station in New South Wales in 1883 when mineral samples taken from an adjacent piece of land suggested the potential for mining. Silver was discovered in 1885. McCullough retired to England in 1891 as a man of wealth.

He and his wife Mary Agnes Mayger (who had been his housekeeper) settled in London at 184 Queens Gate. At this point, McCullough embarked on a career as a renowned collector and patron, with a focus on modern British art. He became a patron of John Singer Sargent, who painted his portrait in 1901. George died in 1907, and in 1909, Agnes exhibited the McCullough Collection of Modern Art at the Royal Academy Winter Exhibition in Burlington House. Press accounts of the sale included fascinating photographs of the McCulloughs enjoying the art-laden interior of 184 Queen’s Gate, possibly taken by George himself.

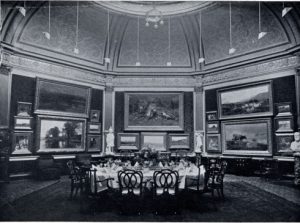

In one view, an imposing Agnes leans on a table, poised between William Quiller Orchardson’s Master Baby and John William Waterhouse’s Ophelia. Other masterworks are visible in a view of George and Agnes posing with their collection, as if seated on thrones. The spectacular domed dining room featured an interesting twist on the notion that scenes of hunting were appropriate decoration for such a space–they displayed numerous animal paintings, including a lion scene by Rosa Bonheur. These creatures, still fierce even in repose, seem to warn guests that humans can be hunters as well as hunted. The breadth and diversity of the collection is astonishing, especially given the casual way in which Mrs. McCullough interacts with the art. As Nancy Rose Marshall reminds us, “a glance at George McCulloch’s collection reminds us of the extraordinary diversity of the art of this period, as Dicksee’s [Funeral of a Viking] resided comfortably alongside more avant-garde works such as the 1892 Self-Portrait by James McNeill Whistler or Jules Bastien-Lepage’s Potato Gatherers of 1878, as well as near other academic works such as Frederic Leighton’s Garden of the Hesperides or Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s The Sculpture Gallery.” The McCulloughs, it seems, had a capacious view of what constituted “modern” and “British” art in this moment, one guided by the art dealer David Croal Thomson. This aesthetic extended to interior decoration as well. As Caroline Dakers has noted, he commissioned stained glass windows from Morris and Company, as well a Morris & Co. Hammersmith carpet, with its distinctive fringe. (the design was christened “The McCullough”). He also bought a partial set of Edward Burne-Jones’s “Holy Grail” tapestries.

No. 184 is the third house from the right. https://rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com/2013/02/14/mrs-mccullochs-house/.

184 Queen’s Gate was severely damaged by wartime bombing in 1944 and finally demolished in 1971 (the Library Time Machine blog of the Local Studies division at the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea lively tells a fascinating story about how a cache of McCullough photographs came into their holdings.) The collection did not suffer a similarly dramatic fate. Instead, parts of the collection were sold or donated at various moments after George’s death in 1907. Agnes remarried and sold some works in 1913 and held another sale another in 1919, at exactly the moment when even the more “avant-garde” works such as Whistler or Bastien-Lepage were unfashionable. Many of the paintings entered another type of display: some were purchased by Lord Lever and became part of the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight gallery, while Agnes gave others to the Broken Hill Art Gallery in New South Wales and the Art Gallery of South Australia.