Recovering Middle Class and Working Class Interiors: Walter Crane in Ancoats

A previous post reviewed recent studies in the history of interior design, focusing on questions of methodologies, especially in an area that is rich with interdisciplinary interest. We concluded by asking how art historians might work to recover the interior, and perhaps the interiority, of middle and working class individuals. In order to begin to answer this question, we have turned to a recent book by Jane Hamlett, Materials Relations: Domestic Interiors and Middle-Class Families in England, 1850-1910 and, in commemoration of Labor Day (at least in the United States), the work of the artist-socialist Walter Crane.

Hamlett begins with a recollection by Winifred Peck, a clergyman’s daughter who grew up in a vicarage in Leicestershire in the 1880s. As she noted, the children in the home “lived on a different plan” from the adults, a separation engendered by the physical space of the home: children in the nursery, rarely allowed in the drawing room. For herself, Peck had come to appreciate this organization of the family and the air of “mystery and enchantment” that it gave to adult spaces and adult lives. In what follows, Hamlett draws upon the idea that “the domestic spaces that people create and the objects they choose for them can both reflect and shape their identity, emotions, and relationships” to recount the “materials relations” that held together middle class families in the late Victorian era. In so doing, she must address the intersection of two important and thorny concepts: consumption and taste. Possessions were important to the Victorians, and they had more opportunities than ever before to acquire things in new and different ways. Yet how did they determine what to buy? Hamlett makes the important point that taste is not “automatically emulative.” In fact, she argues that it is important to move away from the moment of consumption, to examine “the life cycle of the object as it was used in the home after it was purchased.” This task, however, is often frustrated by the challenges of reconstructing or recognizing such interiors through descriptions or in photographic archives, a challenge that becomes even greater in relation to working class interiors. One possibility would be to examine works of art specifically created for working class audiences.

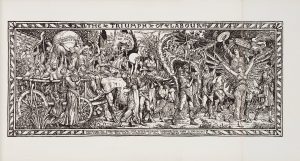

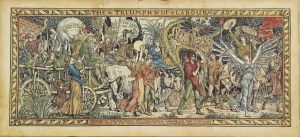

One example that lends insight into the interior decoration of working-class homes is the wide dissemination of political prints by Walter Crane. He created his most famous commemoration of the socialist May Day celebration, The Triumph of Labour, in 1891. It would become the definitive image of English socialism. Borrowing slogans and emblems (such as the Phrygian bonnet) from the French Revolution and English trade unionism, the cartoon celebrates the unity of industrial, agricultural, and artistic labour rendered as the happy progression of liberated workers through a setting of natural bounty. An agricultural worker on the right announces the victory of labour with his pitchfork; following behind, industrial labourers carry a banner proclaiming “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,” a citation that refers not only to the French Revolution but also to a banner Crane had designed for the South London Liberal and Radical Club. Rich with allusions, dense in imagery, The Triumph of Labour is a compendium of Crane’s artistic practice. At the far left, signalling his faith in the intertwined nature of art and labour, he portrays himself holding aloft a palette and riding beside an architect in a wagon bearing the standard “Wage Workers of all Countries Unite.”

According to G. K. Chesterton, writing in 1912, socialists recognize each other “on the fact that a man of their sort will have . . . Walter Crane’s ‘Triumph of Labour’ hanging in the hall.’” In H. G. Wells’s Kipps: The Story of a Simple Soul, the eponymous protagonist observes in the room of his friend Sid, “a Labour Day poster by Walter Crane on the wall.” The April 7, 1888 issue of Commonweal notes that one of Crane’s cartoons was for sale with “Price Twopence.” In 2005 currency, this is equivalent to about 50 pence, according to the National Archive’s currency converter. At the time, the print costs as much as one night’s lodging, or a pint of gin. Numerous owners of Crane’s socialist political prints such as The Triumph of Labour colored in his designs, situating “coloring” within the collaborative ethos and crafted utopianism of Crane’s socialism. Positioned in front of Crane’s designs with paintbrush in hand, the colorist mirrored the pose of the artist himself in this very print. By filling in red and green, blue and yellow, this individual came to know Crane’s imagery in a different way, moving it from the realm of the virtual to the actual. In this way, these colored prints are akin to Crane’s watercolors of decorative designs; they are preparatory studies or blueprints, an ideal depicted but not yet realized.

Andrea Bowers, “The Triumph of Labor”, 2016. Marker on cardboard. 108.75 x 248 x 6.5 in. (276.23 x 629.92 x 16.51 cm). On display at the Jewish Museum.

In the post-Occupy Wall Street moment, Crane’s designs have taken on new life. Since 2012, the contemporary artist Andrea Bowers has reworked prints such as The Triumph of Labour on a grand scale in black marker against a patchwork of cardboard shipping boxes, not unlike those filled by the silent bodies of an Amazon shipping fulfillment center. The mural-scale of this adaptation removes the domestic context from Crane’s work, even as it reinforces the central place of the worker in late, late capitalism.

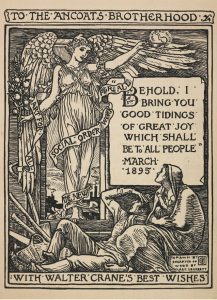

Through the dissemination of other motifs adapted from his paintings in graphic work, Crane created a uniform and pervasive visual culture for socialism that extended to the Ancoats Brotherhood in Manchester. A descendant of an artisan family in Ancoats, Charles Rowley brought his own distinct brand of practical socialism to Manchester while running a successful picture-framing business. He was founder and patron of the Ancoats Recreation Committee (founded in 1882) and, later, the Ancoats Brotherhood (established in 1889). He oversaw a program of lectures, exhibitions, and classes that combined a cultural agenda with progressive politics to improve living conditions in the Ancoats district. As Rowley asserted, “it is a common error to suppose that art is a luxury. In the best sense of the word it is a necessity.” Born and raised in Manchester, Rowley dedicated much of his life to the service of the city, as bureaucrat (he became magistrate of Manchester in 1893), philanthropist, and agitator. He drew inspiration from his father, “a Radical of the old type and a Peterloo man,” and in 1875 became a member of the City Council with the election slogan “Baths and wash-houses and public rooms for Ancoats!”

In one design for Ancoats, the supine and chained worker is visited by the angelic embodiment of Freedom in a card dated March 1895. This card was one of many Crane offered to the Brotherhood over the years, usually inscribed with the greeting “Peace on Earth and Goodwill Towards Men.” Mottoes explain the allegorical associations of the female figure, as she represents “The New Social Order” with “Hope for All,” “Work for All,” and “Art for All.” The burning lamp of unity proclaims, “One for All and All for One.” Crane’s design later appeared in the Ancoats pamphlets and thus entered the home of Manchester’s industrial workers at the very moment when Rowley and T. C. Horsfall, the champion of an art museum for Manchester, asserted the educational role of art and museums, especially in Ancoats. The angel in Crane’s design carries the banner of “A New Social Order,” suggesting the radical potential of Rowley and Horsfall’s enthusiasm for social reform. In the circulation of signs between painting, illustration, and political design, this particular emblem emerges as a unifying motif that asserts the centrality of the artist in creating this vision. And the recovery of these and other examples of working class decoration is a vital part of art’s history.