Decorating with Prints: The Sitting Rooms at Balmoral

The cover of the “keepsake” edition of Queen Victoria’s Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands, published by Smith, Elder & Co. in 1868.

Queen Victoria and her Prince Consort Prince Albert made their first visit to Scotland, including the mountainous northwest known as the Highlands, in 1842, reportedly at the request of the Queen herself. They began arrangements to make Balmoral Castle a royal family home as early as 1848, and they soon established an annual residency in the Highlands. It was the first place she visited after the death of Prince Albert in 1861, and her final stay at Balmoral came only three months before her death in January 1901. The connection was as emotional as it was steadfast: her lady-in-waiting Lady Lyttelton noted that leaving the Highlands was “always a case of actual red eyes” for the Queen.

The secluded location of Balmoral was meant to suggest some degree of royal privacy, but life there became public with the appearance of Queen Victoria’s first Highland memoir Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands, a sentimental narrative of royal life dedicated to Prince Albert and published in 1868. Victoria was increasingly savvy in the ways in which she used the press and publications such as this one to shape her public image. She had entered a period of deep mourning upon the death of Prince Albert in December 1861 and all but disappeared from the public eye until the State Opening of Parliament in February 1866. The publication of her journal reminded readers of Victoria’s public role while also paying homage to the Prince Consort and an idealized version of the domestic life of the royal family, allying domesticity to sovereignty.

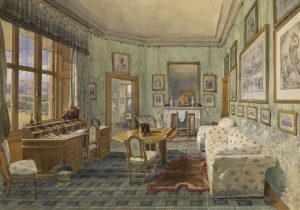

This interplay of general and specific, especially in the negotiation between public and private in the depiction of royal life, is also the theme of two illustrations in the keepsake edition of the journal published for the Christmas gift book market in late 1868. Among the more than seventy illustrations are two chromolithographs of Balmoral interiors after watercolors by James Roberts, a versatile artist who specialized in interior scenes for the queen’s family. The views of the Queen’s and the Prince Consort’s sitting rooms date from the artist’s visit to Balmoral in 1857, when he was asked to produce twelve interior scenes, some of which would be given to Princess Victoria, the Princess Royal, upon her marriage to Prince Wilhelm of Prussia. Six remain in the royal collection and the rest were sent to Berlin.

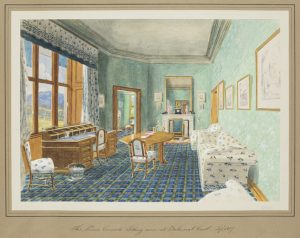

While Roberts’s original watercolors of these sitting rooms do not survive in the Royal Collection, the chromolithograph of the Prince Consort’s sitting room in the journal suggests that the room encapsulates his interests: the desk suggests his diligence in his work, with books and papers stacked on the adjacent table, yet the magnificent view from the window indicates his love of the Highland landscape. The Queen enlisted Holland & Sons to decorate the rooms with specially designed fabrics and a Highland theme, and the Prince Consort’s sitting-room used the Hunting Stewart tartan as a carpet pattern, with a thistle-and-heather pattern for upholstery and drapery. In this space, a print of the Sistine Madonna by the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael can hang above the sofa while the fire screen rests on a buck skin rug. The Queen’s room, in contrast, has comfortable overstuffed seating and a homey tablecloth of Balmoral tartan. Prints after Landseer hang on the walls–including what appears to be a print after Landseer’s Monarch of the Glen (1851)–and a table in the middle of the room hosts family mementos.

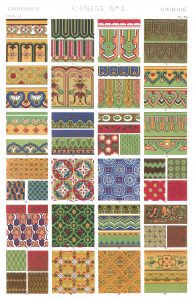

Plate LX (60): “Chinese Nº 2” from Owen Jones, The Grammar of Ornament, folio edition, London: Bernard Quaritch 1868.

Chromolithographs added flat areas in bright colors, toned or enlivened by stippling as needed, through the use of multiple lithographic stones tinted and printed in succession. By the 1850s, the technique was associated with the reproduction of decoration and interiors, in part due to Owen Jones’s lavishly illustrated Grammar of Ornament (1856), printed by Day and Sons. By 1868, that firm was known as Vincent, Brooks, Day, and Sons, and they were renowned for their skill in chromolithography, producing the weekly color prints for the new illustrated magazine Vanity Fair. Chromolithographs thus occupied a dual position in mid-nineteenth century illustrated print culture: they were associated with cheap and popular imagery, meant to appeal to the masses, and they were also featured in elaborate and expensive folio volumes. The Royal Collection also houses what can only be described as an attempt to replicate Roberts’s watercolors: photographs of Roberts’s painting that were then hand-colored by the artist William Corden the Younger.

WILLIAM CORDEN THE YOUNGER (1819-1900)

Queen’s Sitting Room at Balmoral Castle 1857

Watercolour painting over photograph | 19.9 x 28.8 cm (image) | RCIN 916898

WILLIAM CORDEN THE YOUNGER (1819-1900)

The Prince Consort’s Sitting room at Balmoral Castle 1857

Watercolour painting over photograph | 19.8 x 28.0 cm (image) | RCIN 916901

The chromolithographs in the Queen’s journal draw simultaneously upon these two sets of associations. As color images of royal interiors, they offer a privileged view of private life. Their color sets them apart from the other illustrations, and they are bound so that they face another, a practicality that nevertheless evokes the architecture noted in the caption: the Queen’s sitting room opens into the Prince’s. These rooms—decorated with tartan, adorned with keepsakes and hung with engravings—take on a dual function in the text. Emptied of royal family, guests, and servants, they remind the reader that life in the Highlands is best lived outdoors. Yet the emptiness is also the loss that came with the death of the Prince Consort. This logic governs the journal itself, which, as Margaret Homans has noted, is a presence that marks an absence—the absence of Albert, and the absence of Victoria from public life. The chromolithographs participate in this temporal confusion and suspension. Although they are dated 1857, the reader in 1868 may have recalled the Queen’s insistence that nothing change in his spaces in the royal residences after his death. These ellipses and absences point to what Rebecca Steinitz has describe as the feeling of loss that permeates the text of the journal. It is a volume that “frames domesticity primarily in the context of its loss, that is, as a site of desire impossible to realize, a place traveled toward but never fully reached.”

For this reason, it seems strange that a hand-colored photograph in the Royal Collection shows the Prince Consort’s sitting room with a different selection of prints. It must have been that he changed the decoration sometime between Roberts’ visit in 1857 and his death in 1861. Most notably, he added another Raphael: a large print after the Disputa in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican. Perhaps this print, like the Sistine Madonna is part of the prince’s Raphael Collection, an early attempt to provide a complete visual record of the work of the Renaissance artist. In this way, the sitting room presents the prince as a scholar: he has assembled these prints for study rather than for the magnificence of the display.