Rachel Whiteread and the Ghost(s) of Christmas Past

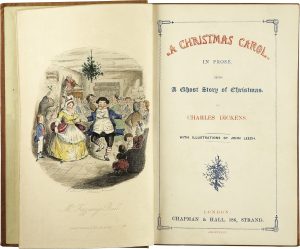

Frontispiece and title page from the first edition of Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Ill. John Leech. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843. Image courtesy of wikimedia commons.

This year we mark the season with some musings on interiors and contemporary art, continuing a tradition we started a few years ago with our posts on holiday decorations, their relationship to historic interiors and museum display. One of the texts that I love to revisit annually is Charles Dickens’ short story A Christmas Carol, first published in 1843. This story wonderfully evokes the varied spaces of Victorian London, whisking the protagonist, Ebenezer Scrooge, from the safety of his bedroom through an array of interiors marking significant moments in his life.

The original illustrations, provided by John Leech, beautifully mirror the spirit of the story. The frontispiece, for example, depicts the interior of a London warehouse, which Scrooge’s first employer, a jovial and generous character, had transformed into a ballroom on a long-ago Christmas Eve; as Dickens writes, “the warehouse was as snug, warm, and dry, and bright a ball-room, as you would desire to see upon a winter’s night.” Leech’s illustration captures the joyous spirit that infused the warehouse, populating it with merry characters. Leech also deftly organizes the composition so that the trappings of domesticity with which the warehouse had been temporarily outfitted, such as upholstered chairs at right and an abundantly large sprig of holly above, frame the scene. In Dickens’ text, Scrooge’s own house likewise reflects his character. Intriguingly, it is not a “house” at all, but rather a “gloomy suite of rooms in a lowering pile of building,” the rest of which had long since been let out as offices. Scrooge is the sole occupant of a house that is now void of the warmth of family habitation and decoration that Dickens ascribes to the other domestic interiors Scrooge visits during the course of the story, those of his nephew Fred and his beleaguered employee, Bob Cratchit.

This winter, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. is hosting an exhibition of work by the contemporary British artist Rachel Whiteread, which closes January 13, 2019. Whiteread’s work, which uses the ubiquity of Victorian domestic architecture in London to reflect on contemporary concerns, made her name in 1990 with her sculpture Ghost, which consists of a plaster cast of the interior of a Victorian sitting room from a house at 486 Archway Road in North London. In 1993 she went on to realize this idea on a grander scale, by creating a cast of an entire terraced house at 193 Grove Road, London, to create a public sculpture titled House. By the time Whiteread made her artistic intervention the rest of the terrace had been demolished to make way for redevelopment of the area, and House itself was demolished a few months later as building work moved forward.

Rachel Whiteread, Ghost, 1990. Plaster on steel frame. Gift of the Glenstone Foundation. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

It seems to me that Whiteread’s work offers us an opportunity to connect the contemporary themes with which the artist is concerned with those that interest here at Home Subjects—the relationship of the viewer to the artwork in the context of the domestic interior. Ghost and House turn that relationship around, as the interior and the surfaces of its walls themselves become the artwork, and the viewer is situated outside of the interior to look onto it. As Whiteread herself said, Ghost and House both cause the “viewer to become the wall.”

Dickens’ story and Whiteread’s sculpture may not seem a natural fit for mutual consideration. Initially when I thought about writing this post, my instinct was to turn to the work of architectural historian Robin Evans, whose nuanced thinking about the plans and inhabited spaces of Victorian houses has been formative in my own work. However, on further reflection the Whiteread exhibition inspired me to return to another favorite text, Sharon Marcus’ Apartment Stories, published in 1999. Marcus’ book invites us to consider the Victorian ghost story as a metaphor for the complicated cultural work that the idea of the “house” (as opposed to the flat or apartment) did—and does—in British culture.

Marcus explains that the British fixation on the space of the private house was a critical marker of English national identity in the nineteenth century. The rejection of the continental (French) model of building purpose-built flats to respond to the ever-increasing demand for housing in Victorian London was a choice made largely based on adherence to an ideology of domesticity that insisted upon the single family dwelling. As Marcus writes, this expression of the notion of the “Englishman’s home as his castle” emphasizes the extent to which the idea of the house was both a masculine formulation and one that coded the English house as a place that was durable, “a bulwark against the losses effected by the passage of time and as an embodiment of a persistent, unchanging version of the past that could be transmitted to future generations (Marcus 92).” However, as Marcus writes, in practice the ideal of the single family dwelling could only be imperfectly executed—the expense of such dwellings meant that many were subdivided, or families took in tenants, so that houses often played host to idiosyncratic living arrangements that seemed to defy their original intent.

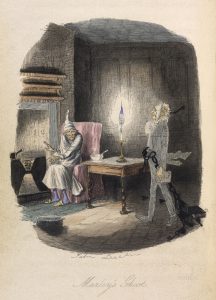

John Leech, “Marley’s Ghost,” in Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843. Image courtesy of wikimedia commons.

Marcus weaves these strands together by considering of one of the classic forms of Victorian writing: the ghost story. Often set in contemporary London, ghost stories “broadcast the urban deformation of the domestic ideal…they set in motion ghosts who attacked the middle-class home’s status as an insular, individuating single-family structure (Marcus 122).” Indeed, to return to A Christmas Carol, Scrooge’s own dwelling reflects this Victorian reality, as he inhabits rooms in what was once a family house, now become a bare and unwelcoming patchwork of offices. Leech’s illustration emphasizes the barrenness of Scrooge’s room. The candle that occupies the center of the images illuminates the bare walls and floors, revealing the sparse furnishings and meagre fire, and hinting at the “quaint” tiles bearing Biblical scenes lining the interior of the large fireplace, which Dickens describes as “an old one, built by some Dutch merchant long ago.” This is an interior that once offered a home to occupants who were invested in its decoration, but whose only remaining trace, the tiles, are now both out-of-fashion and unappreciated by its current inhabitant.

We might also return to Whiteread’s sculpture, Ghost, with Marcus’ exhortation in mind. Even as Ghost memorializes and makes permanent a Victorian domestic interior, its making was only possible given that the house was to be torn down. Its walls take on the status of an artwork, preserving the surfaces upon which frames once hung, to be viewed from the room’s interior and reflected upon as works that were likely decorative, but which also carried the weight of inheritance and history. As the “viewer becomes the wall,” to adopt Whiteread’s own formulation, so too does the viewer become the ghost haunting its former inhabitants, watching, projecting their own memories onto the room’s volume, which can be inhabited only through imagination but never again by the viewer’s physical body.