Self-Made Men: Lord Chesterfield and his Library Portraits

Editor’s Note: Today we have a post from Vincent Pham, who is a PhD candidate in the Visual Arts department at the University of California, San Diego. The following post is a shortened version of the talk Pham presented at the HECAA conference in November 2018, some of which I previously recapped. —ANR

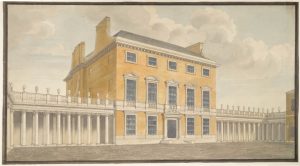

This project is based on the library portrait collections of Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield. Chesterfield House, previously located in Mayfair, London, was constructed by Stanhope and Isaac Ware (1704-1766). Chesterfield was a statesman and writer, who was best known for being the model of a polite nobleman and man of letters. Lord Chesterfield’s reputation and popularity would come from his political career, but also due to a series of publications made during and published after his life. His most influential source of writing, arguably, are the Letters to His Son on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman, published posthumously in 1773. Chesterfield would come to create a London palazzo that would serve as his home base, rather staying at the traditional northern county seat at Bretby, Derbyshire. It was designed by Isaac Ware, with the library being described in Chesterfield’s own words as “one of the best in England.”

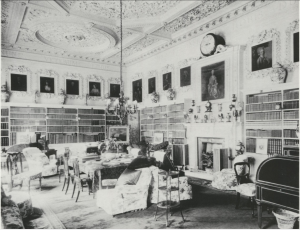

Chesterfield House was composed in the Palladian tradition, while its interior was very much Baroque in its decoration. We can see the heightened use of pediments over the windows, as well as the symmetry that Palladio was so well known for in the drawing of the house contrasts heavily with the intricacy and attention to detail found in the interior decorations. The Baroque pattern continues to the frames that enveloped the portraits- these were mounted directly into the walls, and when the pictures were removed, the external frames stayed in place. As a prominent member of King George II’s court, ambassador to the Hague, and orator in the House of Lords, Chesterfield attracted an audience with desire for political and social favor with whom he would meet with at his library. It was not always easy to claim Chesterfield’s attention—those seeking an audience with him often had to compete with his circle of friends, as well, which was closely interlinked with the literary world of London. He was friends with contemporary writers such as Alexander Pope and Joseph Addison. He read works by Congreve, Wycherly, Chaucer, Shakespeare, and others.

The library housed a series of sequential painted portraits on its walls, of which twenty-two are documented in its final version. Chesterfield was both a patron as well as a collector of contemporary art. Lord Chesterfield initially purchased or commissioned (as copies) many of these pictures even before the library at Chesterfield House was completed. The portraits run the range from Geoffrey Chaucer, to Edmund Spenser, Jonathan Swift, and finally to contemporaries of Lord Chesterfield in the forms of Alexander Pope and Joseph Addison. All of the authors portrayed within this library gallery are of middling, or common birth. This is very much a departure from the tradition of portrait ensembles of the past, which emphasized noble families who owned the house, and their likenesses instead.

In this period, houses were often constructed with the display of collections in mind. This idea is especially useful in how we approach Chesterfield’s house and pictures. Chesterfield was very particular about the hanging order of his portrait sequence; this was to be a collection of not family, nor topographical images, but reflective of someone who wished to be known as a well-read man and writer. The library’s portrait sizes tended to be the same dimensions as the ensconced frames that Chesterfield had purpose-built for the library. They are just slightly smaller than another well known portrait sequence by Sir Godfrey Kneller of the members of the Kit-Kat club. Why, then, was Chesterfield obsessed with portraits of British literary figures? Of course the literati figures portrayed within the space of the library makes sense, but I argue that Chesterfield and others homeowners in similar positions wanted to create a presence of authority by way of using this particular type of serialized display. The inclusion of figures from the literati in the space of the library conforms to the principle that decoration should be in keeping with the use or spirit of a room type, but Chesterfield’s hanging programme also deviated from earlier conventions that emphasized rulers or members of aristocracy in favor of the authority of the intellect.

Copy of portrait of Alexander Pope commissioned by Lord Chesterfield for the library at Chesterfield House. Courtesy of Senate House Library, University of London.

Sir Godfrey Kneller, Alexander Pope, 1719. Private Collection. Image courtesy of the British Library.

As a result, examining individual portraits in more detail and how they work within the space of the room yields fascinating discoveries. For example, Chesterfield’s commissioned copy of Alexander Pope’s portrait is unique in that it changes the arm of the sitter—in removing the original’s pose of holding his translation of the Iliad, the commissioned portrait shares the blue head scarf but with the loss of the held book, the arm has been dropped compared to its original. Within the space of the room Pope is well situated, with a series of friends near his portrait, including Jonathan Swift and Nicholas Rowe. Within just this sampling of portraits there are examples of entanglements, complicated stories, and relationships of influence and patronage between the writers. As Lord Chesterfield arranged the portraits to be emblematic of these tacit interactions, a viewer who had read the authorship on display would have understood the complicated web of references he was trying to make. If they didn’t, the portraits would have been an opportunity for a topic of conversation.

In a way, we might be able to read the portraits today not just for their immediate content (that is, their likenesses), but also being similar to an acknowledgements page within a book, an early version of a paratext. Paratext is best explained as the elements which lie on the threshold of a text that seeks to help direct and in some cases, control, its readers. Authorial presence and portraiture were mobilized in such a way that visitors to the space would be able to identify not just Chesterfield’s personal connections to, but also his connoisseurship of British authors, poets and playwrights. The presence of the authors functions almost as a paratext—a visual text that would work affect the reception of Chesterfield’s guests. Chesterfield then, was interested in the construction of a literary canon. If we take the portraits not to be primarily purpose-built to function as repositories of likeness, but more of indicators of what books to consult, and with Isaac Ware’s frames’ permanent status in the house until its destruction, it will be interesting to consider these portraits as disposable. After all, Chesterfield House’s library frames act to enclose its contents: but very much like James Grainger’s blank folio pages, these frames also act as the structure that remain permanent. The copies commissioned throughout Chesterfield House’s history are fungible- it is the frames that stay, while the pictures are mobile, and like changing ideas of canonicity in the eighteenth century, are subject to revision.