May Morris: Art & Life, New Perspectives

William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow, in William Morris’s former childhood home, recently featured the exhibition May Morris: Art and Life (7 October 2017 to 28 January 2018). Highlighting more than 80 works that showcased the diversity of Morris’s interests, from drawing to jewelry, the exhibition gave rise to two separate publications. One, from Thames and Hudson, May Morris: Arts and Crafts Designer, serves as the exhibition catalogue, and includes essays by Anna Mason, Jan Marsh, Jenny Lister, Rowan Bain, and Hanne Faurby. The stated aim of both exhibition and publication is to move May Morris out of the shadow of her famous father, William Morris, by exploring the full range of her work and her importance to the Arts and Crafts movement well into the 1920s.

May Morris: Art & Life, New Perspectives, edited by Lynn Hulse, is the second exhibition-related publication. It has a more complicated history, and offers a more complex, and complicated, picture of May Morris. Hulse is a textile historian and embroiderer who worked with the William Morris Gallery to convene a conference in May 2016, in advance of the exhibition, from which the thirteen essays in her volume were drawn. These essays range from biographic explorations to technical discussions of embroidery, to Morris’s role in furthering her father’s legacy. The volume explores new archival material and provides new interpretations of Morris’s life and work, including the business of Morris & Co., especially the embroidery department managed by May. While both volumes will be of interest to Home Subjects, this post will offer an overview of the essays presented in this earlier publication, exploring how the book negotiates an important but difficult position for May Morris in the legacy of the Arts and Crafts movement.

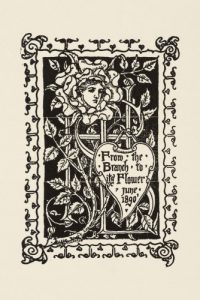

The essays assert Morris’ place as an artist in her own right while acknowledging that many of her opportunities came from her access to a privileged artistic and cultural milieu. Jan Marsh provides a biographical and historiographical overview of Morris’s life and work. She situates Morris as “New Woman,” one whose choices and actions prioritize personal freedom. Yet as Anna Mason demonstrates in her essay, “May Morris: Socialist Agitator,” it is important to remember the social limitations of even the most radical groups of the nineteenth century—as demonstrated by the bookplate “From the Branch to the Flower.”

Woodblock printed bookplate, inscribed “From the Branch to its Flower,” designed by Walter Crane and engraved by W.H. Hooper. William Morris Gallery.

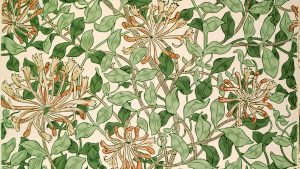

Designed by Walter Crane to accompany a wedding present of books from the Hammersmith Branch of the Socialist League in June 1890, the design manages to celebrate Morris for her ornamental quality—she is the flower—even though she designed papers such as “Honeysuckle” for Morris & Co. The trellis that supports the climbing rose with Morris’s face forms the initials of Henry Sparling, her fiancé, but it is also reminiscent of her father’s Trellis wallpaper. Probably unwittingly, Crane manages to comment on the personal and professional challenges that May Morris faced. Her marriage would end in divorce in 1896.

In her essay, Anna Mason argues that political work—fundraising, meetings, and public speaking—prepared Morris for the assertive independence of her later work. Yet, as Rowan Bain notes in his, Morris was dependent upon the executors of her father’s estate; she was required to submit quarterly accounts of her expenditures, and was often subjected to paternalistic advice from executor Sidney Cockerell, who was five years her junior. Morris emerges in Bain’s account and later essays in the volume as a dutiful daughter sometimes overwhelmed by the weight of her family legacy.

Lily Yeats and her assistants in the embroidery room at Dun Emer Guild, Dundrum, 1905. Women’s Museum, Ireland.

The middle section of the volume delves deeper into Morris’s life as an artist while retaining the biographical model. Catherine White details Morris’s experience as the manager of Morris & Co.’s embroidery department (1888-1896), including her fractious relationship with Lily Yeats, the sister of the poet W. B. Yeats, who would go on to set up the embroidery department of the Dun Emer Guild in 1902 and the Cuala Industries in 1908. Lynn Hulse combines this interest in the practice of embroidery with the consideration of the history of the needlework in her discussion of Morris’s interest in Opus Anglicanum. Morris’s knowledge of medieval embroidery, and her belief that they were superior to modern examples in technique and artistry, became a key feature of the Arts and Crafts movement. This theme re-emerges in Annette Caruther’s essay on May Morris’s visits to Melsetter House in Orkney, where she stayed with Theodosia and Thomas Middlemore in a home designed by W. R. Lethaby.

Lynn McClean, Principle Textile Conservator and Emily Taylor, Assistant Curator (right) display the Morris hangings. Neil Hanna Photography.

May and Theodosia shared an interest in embroidery as well as the local traditions of yarn spinning and dyeing; Morris created a beautiful series of embroidered hangings for Melsetter that were worked by May and Theodosia and are now in the collection of the National Museum of Scotland. This essay is the first in the volume to situate Morris’s activities in relation to the Home Arts and Industries Association that promoted craft work as a way for women in rural communities to contribute to the household income. Often organized by middle- and upper-class women as philanthropic endeavors and supported by landowners, the Home Arts sought to busy the “idle hands” of the agricultural workforce without actually raising wages. Morris did not express much interest in these activities, and she focused instead on the training of skilled embroiders and needlework designers, especially in her time as Special Teacher at the Birmingham School of Art, as discussed by Helen Bratt-Wyton. These and other essays, including Mary Greensted’s discussion of Morris’s relationship with Ernst Gimson, from whom she commissioned Morris Memorial Hall in Kelmscott, place Morris firmly within the center of a vital social and artistic milleau.

Morris’s indifference to the Home Arts can be contrasted with her effort to address the artistic contribution of women artists through the Women’s Guild of Arts, founded in 1907. Modeled after the all-male Art Workers’ Guild, the organization provided a forum for members to exhibit and discuss their work as artists and designers. The list of members detailed in Helen Elletson’s essay reminds the reader of the rich diversity of female artistic production around the Arts and Crafts movement, a topic that has not received sustained consideration since Anthea Callen’s Angel in the Studio (1979).

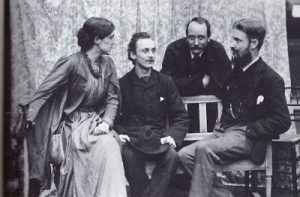

May Morris, Henry Halliday Sparling, Emery Walker and George Bernard Shaw, 1889. Photograph: Walker & Boutall. National Trust on behalf of the Bernard Shaw Estate.

Of special interest to Home Subjects readers will be tantalizing details about what it meant to live in a house full of art. Kathy Haslam considers the importance of Kelmscott and Kelmscott Manor to May Morris’s sense of self, touching upon her relationship with her companion in her later years Mary Lobb. (There is more to be said about this relationship in terms of same-sex affection and queer identity, issues which were not pursued in the volume). The two lived a Spartan lifestyle amidst Arts and Crafts luxury, as the house did not have electricity or running water. The Society of Antiquaries cares for the house now, and they were awarded a major heritage grant in 2018 to reinterpret the spaces and ensure its future sustainability. The record of the interiors, especially during William Morris’s lifetime, are incomplete composites of photographs by Emery Walker, memorandum written by May, and other accounts to visitors. May Morris experienced the house as a lived space and envisioned it as a heritage site.

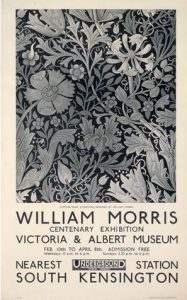

Perhaps the most poignant moment in the volume comes in Julia Dudkiewisz’s discussion of May’s role as the “memorializer” of her father. Not only was she the editor of the twenty-four volume Collected Works of William Morris, but she also lived in a mostly empty house during the V&A’s “Morris Centenary Exhibition” of 1934. She was the largest private lender to the exhibition, and assumed the role of co-curator, writing, advising, and even revising the attribution of objects. In doing so, May agreed to have eighty objects removed for the duration of the exhibition. The Arts and Crafts melding of art and life takes on new resonance, as the “life” becomes the subject of a museum exhibition.

While the volume does a wonderful job of bringing new material to light and putting May Morris in the spotlight, more work remains in order to contextualize her life and work. Are we to take at face value Morris’s own assessment of herself in a letter to George Bernard Shaw from the 1930s as a “remarkable woman”? (She followed this assertion with an accusation: “through none of you seemed to think so.”) It is clear from the essays that Morris was indeed a remarkable woman–one whose fame and influence spread to the United States, as discussed by Margaretta Frederick. Morris’s contacts during a lecture tour remind us of the transatlantic nature of the Arts and Crafts movement as well as social reform circles. May offered lectures on a range of topics, from jewelry design to the history of the masque, but she found that one topic dominated the minds of her listeners: “people crowd to hear me . . . but they are disappointed that I do not speak on personal matters. And you can imagine how puzzled the reporters are. The daughter of a great man missing her opportunity and not talking about him.” As these essays demonstrate, there is much to say about May Morris–and much more to be said. We can no longer focus only on “the great man.”