Interior Decorating in Nineteenth-Century France

Anca Lasc, Interior Decorating in Nineteenth-Century France: The Visual Culture of a New Profession (Manchester University Press, 2018)

We are delighted to feature Anca Lasc’s research on interior decorating, the display of art in the domestic interior, and the commercial space of the department store in nineteenth-century France. Home Subjects readers will note fascinating parallels with the spaces of department stores in London, such as Liberty and Selfridges, as well as furniture and design stores such as Heal’s and Maple & Co. into the twentieth century.

This post offers a brief account of how department stores merchandised the domestic space in the second half of the nineteenth century, hiding the commercial nature of their undertaking under the disguise of art. It draws on material from my new book, Interior Decorating in Nineteenth-Century France: The Visual Culture of a New Profession (Manchester University Press, 2018), which argues that a growing visual culture of the interior, encouraged by new, modern techniques of image-making and reproduction, enabled the still-unnamed profession of the interior designer to take shape. In the second half of nineteenth-century France, the ideal domestic interior was represented through various media outlets, including collecting and domestic advice manuals, pattern books, illustrated magazines, art and architectural exhibitions and department store catalogues. Upholsterers, cabinet-makers, architects, stage designers, department store managers, taste advisors, collectors and illustrators “sold” the interior as an image and a total work of art to their customers and the public at large long before Siegfried Bing’s famed Maison de l’Art Nouveau (opened 1895), and all wanted a share in the lucrative business and art of interior decorating.

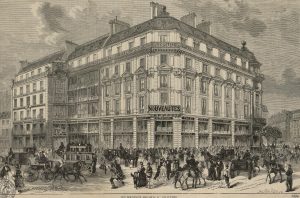

Le Printemps, Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris, [Paris, le Printemps. Dossier iconographique.

Michel Charles Fichot, Magasin “Au Petit Saint-Thomas”, rue du Bac, 7ème arrondissement, Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris.

In c. 1890, the store Au Petit St-Thomas published a catalogue exclusively dedicated to furnishings, with the majority of illustrations dedicated to complete, unified interior ensembles in a variety of historic or exotic styles. Indeed, after spending a couple of pages on instructing readers how to take the measurements for the various drapery or decorative ensembles desired for their beds, windows, and doors, the catalogue displayed an array of illustrations of interior designs, each more artistically rendered than the other. These were very likely idealized representations of interiors that could be achieved with the help of furniture pieces available at Au Petit St-Thomas rather than exact reproductions of furnishing groupings displayed as models on the store’s grounds. Like other contemporary retail establishments, Au Petit St-Thomas found that the best way to sell furniture was through pictures of interiors.

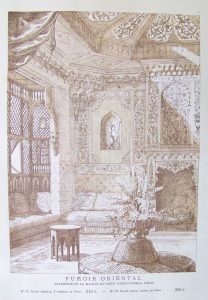

“Fumoir oriental: Tapisserie de la Maison du petit Saint-Thomas, Paris,” Maison du Petit St Thomas: Album de l’Ameublement c. 1890.

A “Fumoir Oriental,” for example, included a monumental fireplace, a magnificent tent-like ceiling, a moucharaby (a projecting latticework window typical in Islamic architecture), and a small nook for the display of the hookah on the wall. Part and parcel of the room described yet not the responsibility of the department store these architectural elements bore no prices on the catalogue’s pages. The publication only displayed prices for the two sofas and the round borne in the foreground. But the amount of attention bestowed upon the representation of the entire architectural ensemble suggests that the representation solely of items commercialized by Au Petit St-Thomas was not what the department store was after. Rather, it was the suggestion of a complete interior, the representation of an artistically-designed, themed room in an exotic style that was believed would boost the store’s sales. One can, indeed, see how the artist spent as much time trying to capture the way that light, filtered through the wooden latticework and glass ceiling, fell onto the various walls and furniture pieces in the room as he did on attempting to accurately render the furnishings commercialized by the store.

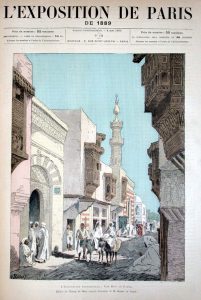

Moreover, the seemingly inadvertent presence of a curtain falling down on the scene from some fixture hidden to the viewer’s eye represents yet another attempt to render a theatrical “interior dreamscape” through the medium of a commercial catalogue, an appeal to the reader’s imagination much like the oft-cited Rue du Caire exhibit at the 1889 exposition universelle had been.Because people were used to consuming images in frames, with painting soon categorized by Henry Havard’s Histoire et philosophie des styles (1900) as the quintessential art of the nineteenth century, the best way to sell furniture was through an interior landscape. And Au Petit St-Thomas’ catalogue purposely veiled its furniture on sale in an artistic aura, which ultimately softened the blow that its images were just ads.