A “House” for the Prince of Wales: The British Pavilion in Paris, 1878

J. McNeven, The transept from the Grand Entrance, Souvenir of the Great Exhibition , William Simpson (lithographer), Ackermann & Co. (publisher), 1851, V&A.

Since the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in 1851, international exhibitions, more popularly known as “World’s Fairs” were important sites for debates about display, domesticity, and decoration, in a global context. Usually organized by a consortium of government agencies, civic organizations, and commercial interests, these events, according to Bjarne Stokland, “grew into gigantic instruments for education and refinement, where contemporary ideas and norms were formulated and imprinted through visual communication.” Yet this communication was not merely visual, as exhibitions provided multi-media and multi-dimensional maps of the cultural world. As such, they were important platforms for the public display of contemporary domestic objects. While the fine arts could be seen in annual exhibitions and commercial galleries, the decorative arts were scattered throughout department stores and independent purveyors as merchandise.

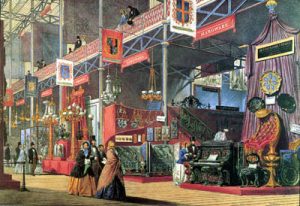

Joseph Nash, “Hardware at the Great Exhibition,” Lithograph, from ‘Dickinsons Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851’, pub. Dickinson Brothers, 1854. V&A.

The same objects on display at international exhibitions were not available for purchase, and they appeared in multiple display contexts throughout the vast exhibition grounds: palaces of industrial art, national pavilions, and commercial exhibits. Is the decorative work of art first and foremost an autonomous object, or does its decorative status compromise this autonomy? These exhibitions managed the divide between “fine art” and “the arts not fine” through the physical organization of objects and the developing discourse of interior decoration in exhibition guidebooks and reviews. These issues gained urgency as the nineteenth century progressed, so much so that by 1889, the Exposition Universelle in Paris had an entire section of the fair devoted to the history of human habitation, with model houses from throughout history and around the world, as imagined by the architect Charles Garnier. It was in Paris in 1878, however, that the ideals of comfort and domesticity first became associated with the British display.

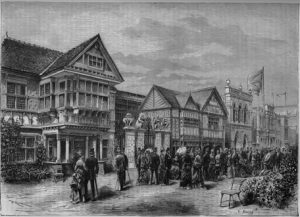

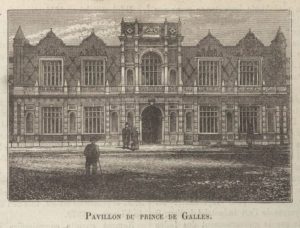

The British Section along the Champ-de-Mars at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878 included five buildings arranged in a row. The first, designed by Richard Norman Shaw, was a red brick home in the Queen Anne style. It was outfitted as a model home by Lascelles and presented itself as an ideal living space for the suburbs or the country, available at an affordable price. It was used for meetings of the Royal Commission for the fair. The second, described as “the Pavilion of the Prince of Wales” or “The Prince of Wales’s Home” was an Elizabethan-revival structure based on a design by Gilbert R. Redgrave, discussed below. This was followed by a pavilion sponsored by the porcelain manufacturer Doulton & Co: a replica of Southbank House, their ornamented red brick and polychromy showroom only recently constructed in the Lambeth area of London, and designed by Tarring, Son & Wilkinson. The next structure returned to the revivalist theme: a half-timbered cottage inspired by the the “black and white” manor houses of Cheshire from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, designed by Redgrave and executed by William Cubbitt and Company. The final building was sponsored by furniture makers Collinson & Lock and decorated in a “William and Mary” style.

For many commentators, the stand-out in this display was the Prince of Wales’s “home,” a model interior that fulfilled its domestic function when the prince visited the fair as President of the Royal Commission. Prince Albert, the future King Edward VII, attending the inauguration of the fair on November 21, 1878, appearing in the opening procession alongside Queen Isabella of Spain. Pavilions such as this one encouraged manufacturers to work together, and in the British context, the added benefit of a royal connection made these attractive venues. Gillow & Co. of Oxford Street provided the furnishings, collaborating with Barnard, Bishop, and Barnard (metalwork), James Templeton & Co. (textiles), and Minton, Hollins, & Co. (flooring). In addition, the Old Windsor Tapestry Works created eight scenes from Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Windsor for the pavilion’s diving room. They hung above a table set with plate by Elkington & Company and a china service by Minton. The display was particularly successful at evoking the feeling of habitation and domesticity: “the disposition of the rooms is perfectly organized for the convenience of those who must live there; the layout is beautifully designed in every way.” Interestingly, this mock domestic interior for the Prince of Wales featured tapestry as the privileged form of royal portraiture and domestic pictorial art.

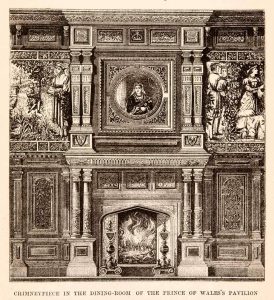

“Chimneypiece in the Dining-Room of the Prince of Wale’s Pavilion,” from G. A. Sala, “Paris Herself Again” (London: Vizetelly & Co., 1882), 136. British Library.

The display in the large dining room, with tapestries by the Old Windsor Tapestry Works, appeared as one of the “wonders” of the fair in a guidebook. The selection of scenes from Shakespeare’s play confirmed the historicist nature of the interior and also advertised the cultural importance of Windsor. Yet Old Windsor was only recently established, in 1876, by two Frenchmen, Marcel Brignolas and Henri C. J. Henry. The latter had been the Art Director at Gillows, Oxford Street. The manufactory relied upon the skilled weavers from the Aubusson works in France who were convinced to make the move to Windsor, although they also hired English weavers. As is often noted, it was one of only two tapestry works founded in England in the nineteenth century–the other being William Morris’s Merton Abbey works. Brignolas and Henry enjoyed the support of Prince Leopold and other members of the royal family. To signal this close interweaving of tapestry works and royal family, their first design was a portrait of Queen Victoria, adapted by Phoebus Levin after a painting by Baron Heinrich von Angeli. It hung over the fireplace in the Prince of Wales pavilion, and it is now in the collection of the V&A. Queen Victoria consented to the designation “Royal” in 1880.

“Ye Merrie Wives” designed by T. H. Hay and worked by Old Windsor Tapestry Manufactory (later Royal Windsor), 1877.

The Merry Wives of Windsor series was commissioned by Gillow & Co. to decorate the dining room at the pavilion, and they were each awarded a gold medal at the fair. The artist T. W. Hay, who had previously worked with Henry at Gillow & Co., designed the series, although the cartoons do not seem to have survived. The first panel “Ye Merrie Wives,” visible to the left of the fireplace in most illustrations of the dining room gives the contemporary viewer a sense of scale, as the panels measure roughly six feet by twelve and a half feet, with sixteen warps per inch. The borders were woven separately and unite the panels through a continuous repeat of flower and fruit panels. “Ye Merrie Wives” depicts Act III, scene III: Mistress Page and Mistress Ford smile nervously over a basket of dirty laundry as Falstaff hides behind a curtain. Although the costumes and the flora suggest Hay’s interest in historical accuracy, the blue and white planter for the orange tree at the center, with a peacock to the right, are unmistakable signs of the burgeoning Aesthetic movement.

Two of the “Merry Wives” tapestries flanking the fireplace in 25 Kensington Gore. Photo courtesy of historichouses.org.

The success of the tapestries as interior decoration, especially as a substitute for painting, was noted by Sir Albert Sassoon. He bought the decor and fittings from the pavilion, and installed them in his own dining room at 25 Kensington Gore. Sassoon came from a family of Baghdad merchants and was educated in India. He made his fortune there in cotton spinning and weaving and settled permanently in London in 1875. It does not seem that the tapestries were in place for long, as Albert retired to Brighton and Aline de Rothschild, the wife of his son Edward, set about redecorating. The tapestries were eventually sold by Sir Phillip Sassoon in 1912. Six of the tapestries showed up at an auction in Christie’s London in September 1978, and the portrait of Queen Victoria entered the collection of the V&A in 1968. The Jacobean-style paneling and mantel remained in place, however, and the current owner bought two of the “Merry Wives” tapestries at auction and has re-hung them in the dining room. 25 Kensington Tour is occasionally opened to the public for tours, which can be booked here.

Detail from “Sir John Falstaff,” designed by T. H. Hay and worked by Old Windsor Tapestry Manufactory (later Royal Windsor), 1877.

What happens to our usual understanding of the Victorian dynamic between painting and tapestry when we place Royal Windsor alongside the Merton Abbey works? Although both stemmed from a historicist or revivalist impulse, they chose different versions of that past: while Morris looked to a Medieval ideal in subject matter, materials, and technique, Royal Windsor emphasized its connection to historical royal tapestry works produced under the patronage of the Tudor and Stuart monarchs. In the “Merry Wives” panels, T. H. Hay exploits the potential for illusionistic effects in tapestry, depicting Falstaff falling out of a scene or a rabbit leaping off of a lawn. The relationship to contemporary artistic trends also buoyed the reputation of Merton Abbey. When William Morris was asked why Merton Abbey succeeded while the Royal Windsor Tapestry Works failed, he concluded, “they had not the advantage of working with Sir Edward Burne-Jones’ designs.” The death of Royal Windsor sponsor Prince Leopold created difficulties for the firm, and they closed in 1890. Nevertheless, these tapestries for the “home” of the Prince of Wales at the exposition universelle in Paris in 1878 provide a singular example of the ways in which world’s fairs promoted British art and design as a domestic achievement and a decorative ideal.

My thanks to the Beinecke Library at Yale University for a visiting fellowship that enabled this research in the Alfred E. Heller of World’s Fair Materials.