Queen Victoria’s Carpet, Part I

“Home Subjects” is dedicated to exploring the history of the display of art in the domestic interior in Britain. As a necessary corollary, therefore, we are interested in the history of interior decoration, as we think about wall coverings, furniture, and lighting in relationship to how and where works of art adorned the home. But what about floor covering? How does the flooring or floor covering affect our experience of a work of art? From the click-clack of heels on polished concrete in a loft space to the soft shuffle produced by high-pile rugs, flooring is an often overlooked aspect of the art-viewing experience. As Caroline Arscott has recently noted, carpets could function as “design in action” in regard to William Morris’s designs, “knotting together” diverse strands of cultural production. Carpets were ideally placed to function as a touchstone in Victorian debates about art and design. Overlooked and yet under foot, the carpet could weave together the diverse strands of art and craft to create a unified interior or strike a false note through debased design and inferior production.

Official christening portrait of Archie Harrison Mountbatten-Windsor, July 6, 2019. Photo credit: Alexi Lubormirski/Kensington Palace.

Take, for example, a rug that has appeared in the news recently, a backdrop (drop cloth?) for photographs of the royal family after the christening of the new royal baby and the official wedding photographs of the Duke and Duchess of Sussex: the Axminster carpet in the Green Drawing Room at Windsor Castle, measuring 52 feet long and 38 feet wide. It is a woolen carpet that features the “VA” monogram (for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert) in three locations. At the center is a grouping of flowers surrounded by thirty-two rectangular panels and a repeating border pattern of flowers on a brown and cream ground. It was designed by L. Gruner at the request of Prince Albert and made at Wilton by Blackmore Brothers for Watson & Bell of Bond Street. The carpet was exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and garnered praise from critics for its coloring, which was judged “brilliant, yet not gaudy.” It was worked by hand, with sixty-four stitches in every square inch of carpet. Thomas Whitty, a weaver based in Devon, was inspired by the Turkish carpets he saw on display at Cheapside Market in London in 1755, and he set out to produce a carpet of similar quality in England. He soon found success with royal and aristocratic patrons, and in 1800, the design-inspiration went full circle when he received a commission from Mahmud II, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. After a fire destroyed the looms in 1828, the firm of Blackmore Brothers of Wilton acquired the remaining stock and expanded their existing business to the include hand-knotted carpets that carried the Axminster name.

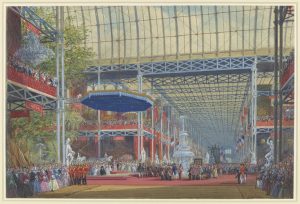

So far, I have failed to find an illustration of the carpet from the Great Exhibition or to locate it in views of the Crystal Palace. Carpets shown by commercial exhibitors were hung in the left-hand north gallery, looking from the south transept, while carpets exhibited by the Queen were shown overhanging the corner near the transept of the North Central Gallery. This position was a prominent one that would have attracted visitors, as it was near the magnificent crystal chandelier made by F. & C. Osler of Birmingham (visible in the upper left corner of Joseph Nash’s watercolor of the inauguration of the Great Exhibition) and adjacent to the crystal fountain made by the same manufacturer that occupies the center of Nash’s image.

Although the Windsor Castle carpet might not look hand-made, it was, and that process was seen as a stark contrast to the products of the power loom in 1851. Also exhibited at the Great Exhibition, a carpet by John Crossley & Sons of West Yorkshire was the embodiment of Victorian ideals of utility, efficiency and aesthetics, c. 1851. In terms of efficiency, Crossley & Sons invested in the latest technology, using steam powered looms to increase productivity and scale. As for aesthetics, this particular design was called “Old Master,” probably a reference to the Rococo curves and floral groupings drawn from historical paintings. Exuberant and colorful, this carpet is a celebration the union of art and technology. And yet nothing could be more controversial in the early 1850s than a flowered carpet.

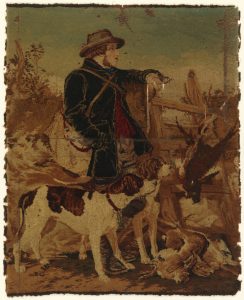

John Crossley & Sons Ltd., Carpet panel from a Firescreen: “The English Gamekeeper,” 1859–1869, Cooper Hewitt.

In response to pieces such as this one, Henry Cole established a “Chamber of Horrors” that dramatically illustrated what he considered to be “false principles of design,” such as the introduction of illusions of depth in what should be the flat patterning of a wall or floor covering. The “chamber” was open to the public in order to educate them on the features of bad design. For Cole, it was the illusion of the carpet, the shading that gave the flowers depth that contravened its purpose as a floor covering. In addition, “Old Master” implied inspiration from a work of art that hung on a wall, a tragic confusion of the purpose of this object. In fact, as this fascinating blog post by Rebekah Pollock at the Cooper Hewitt suggests, Crossley & Sons repeatedly contravened the boundaries between the pictorial and the decorative. An experimental product known as a “mosaic tapestry” reproduced paintings by popular artists such as Richard Ansdell and Edwin Landseer. As Pollock notes, examples of this new technology were shown at the Great Exhibition with an advertisement for its application that disregarded the traditional associations of Crossley & Sons products with floor coverings, “patent mosaic tapestry for the walls of dining rooms; for carpets and table covers; and for covers of sofas and chairs.”

Laurits Tuxen, “The Family of Queen Victoria in 1887,” 1887. Royal Collection Trust. Palace of Holyroodhouse.

Blackmore and Sons did not exhibit such novelties at the Great Exhibition, and the carpet’s design could represent an attempt (however subtle) by Victoria and Albert to remake the Green Drawing room in their own image. King George IV had planned the decor of the room with furniture and fittings designed by Morel & Seddon, a fashionable firm led by the French cabinet-maker Nicholas Morel. According to the Royal Collection Trust, this decorative project was “one of the most lavish and costly interior decoration schemes ever carried out in England.” The original Axminster carpet, visible in a watercolor painted by Joseph Nash in 1848 in the Royal Collection, appears to be of a similar floral design, but on a green ground. Queen Victoria must have admired the space, and her intervention in its design, as she selected it as the location of her 1887 Golden Jubilee portrait painted by the Danish artist Laurits Tuxen. In this extended family portrait, the Axminster carpet is recognizable underfoot, as in the more recent family photographs, and Queen Victoria is positioned next to the stylized ogee of the “VA” monogram.

A future blog post will consider another of the “Queen’s carpets,” also exhibited at the Great Exhibition: the Berlin wool-work carpet embroidered for her by the ladies of London.