Christmas at Osborne House

Since the holidays are upon us, here at Home Subjects we have turned our minds once again to Christmas decorations. In a post from 2016, I commented upon the popularity of the phrase “Victorian Christmas” in marketing Windsor Castle to holiday visitors. At the time, I also noted the popularity of the “Victorian Christmas” and the “Christmas Fair” at Osborne House. This post takes a closer look at Christmas celebrations by the Royal Family at Osborne House and their connection to the decorated interiors there.

As C. S. Lewis noted, “there are not Christmases, there is only Christmas—a composite day made up from the haunting impression of many Christmas days, a work of art painted by memory.” The Christmas decorations and celebrations at Osborne House, a former royal residence built by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in East Cowes on the Isle of Wight, suggest the truth in Lewis’s observation. The estate was presented to the nation by Edward VII at his Coronation in 1902. It fulfilled a variety of functions (private museum for the royal family, military convalescent home) before coming under the auspices of English Heritage. Today, the interiors are decorated for Christmas and the celebration continues on the grounds during a weekend Christmas “fair” that includes a carousel, music, entertainment, and stalls selling holiday-themed merchandise. The website for the event draws upon the popular association of Christmas and the reign of Queen Victoria, inviting visitors to the “celebration of the perfect Victorian Christmas.”

The dining room at Osborne decorated for Christmas with Franz Xaver Winterhalter’s The Royal Family in 1846 in the background.

English Heritage does not aim to recreate the Christmas traditions of Queen Victoria at Osborne House but rather evoke the ideal “Victorian Christmas.” While Osborne House typically welcomes 60,000 visitors for Christmas tours between November and January each year, attendance at the weekend Christmas Fair brings in around 7,000 visitors over two days. The house aims for a “Victorian flavor” to the decorations without reference to any specific historical examples, according to Michael Hunter, Art Curator, Collections Department, Osborne House, and they eschew didactic materials in favor of interaction with costumed stewards stationed in each room.

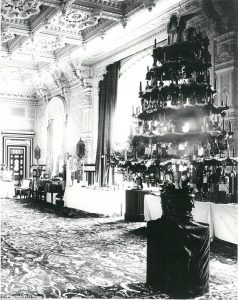

After Albert’s death in 1861, royal family Christmas celebrations shifted from Windsor Castle to Osborne House. Although the Queen’s grief marked the holiday, these celebrations and decorations were as elaborate as those at Windsor. As with the royal family celebration at Windsor, the Christmas traditions developed for Osborne House were also the subject of popular fascination, according to B. C. Skottowe, who described “How the Queen Spends Christmas at Osborne” for readers of the The English Illustrated Magazine in 1897. There is also a wealth of information in Greg King’s chapter “Christmas at Osborne” in Twilight of Splendor: The Court of Queen Victoria during her Diamond Jubilee Year (2007). The Queen spent her first Christmas as a widow in 1861 at Osborne, and she regularly spent December and the first part of the new year on the Isle of Wight. The displays of foliage, Christmas trees, and present tables would take their place alongside key works of art such as Sir Edwin Landseer’s The Deer Drive in the Council Room and William Dyce’s impressive Neptune Entrusting the Command of the Seas to Britannia adorning the staircase. Chimney pieces were adorned with boughs of holly, yew, and fern interwoven with cloves and set with candles. Doorways were framed with garlands of evergreen with holly and ivy. Poinsettias and miniature topiaries were placed on tables. The white marble bust of Prince Albert in the foyer received its own garland of holly and ivy.

Typically, Queen Victoria’s celebration included twelve Christmas trees: the grand staircase, the drawing room, the Queen’s sitting room, the dining room, Princess Beatrice’s suite, and rooms for the royal household. The decorations at Osborne House today evoke some of these installations. For example, they place a small Christmas tree on a table in the Queen’s sitting room and a larger tree in the dining room. The trees in the dining room were initially the focus of family celebrations. When the Durbar Room, the magnificent banqueting hall at Osborne House created by Sikh artisans, was completed in 1892, it became the site of Christmas celebrations until the Queen’s death in 1901. As B.C. Skottowe described, “The great sideboard is loaded with gold plate which has been polished till it gleams like glass. A mighty Yule log sent from Windsor glows on the hearth. The strong red and green of the decorations contrasts very prettily with the subdued Oriental coloring of the walls. The table glitters with plate and glass and candles and the dessert is adorned with the unusual pomp of flags and crackers in all the glory of tinsel and gelatin. At the head, the Queen takes her seat. Round it her family group themselves in order, the children enjoying the mere fun of taking their places.”

The anthropologist Daniel Miller outlines two Christmas tendencies: the carnivalesque and the centripedal. The Christmas decorations at Windsor Castle are centripedal, a display that “stabilizes around the basic unit of sociality and then gradually extends” outwards to include the visitors and the nation, as well as an international audience that consume images and content online. In contrast, the decorations at Osborne House could be carnivalesque. After all, it features a Christmas carnival as part of the popular “Victorian Christmas” celebration. Yet, as Miller notes, most Christmases are both at the same time, as contradiction and ambivalence can pervade celebrations. In historical terms, the display of the royal family’s Christmas presents in the Durbar Room can be seen to both support and unsettle Victoria’s position at Empress of India. The relocation of a family celebration to a ceremonial space designed to exalt the fusion of British and Indian design and craftsmanship was a further marker of sovereignty. The very decoration of the room, however, is reduced to a kind of festive backdrop to a Christian-inspired celebration. How does the presence of the Ganesha, god of good fortune, affect the Christmas display of luxurious tokens of familial affection? Maybe it depends on the gift. Today, the Durbar Room once again hosts a display of gifts as the home of the Osborne Collection of gifts given to Queen Victorian to mark her jubilees in 1887 and 1897. Many of these are caskets containing written tributes to the Queen from across the Indian Empire.