Queen Victoria’s Carpet, Part II: Still Life and Berlin Wool Work, c. 1851

In a blog post from 2019, I discussed the Axminster carpet in the Green Drawing Room at Windsor Castle, created for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1851 and exhibited at the Great Exhibition. This post will examine a second carpet with connections to the Queen, and how it might relate to the display of art in the domestic interior. The “Ladies Carpet” was executed in Berlin wool-work and displayed prominently at the Great Exhibition in 1851.

Around 1850, the still-life painter George Lance, praised by the art journalist Samuel Carter Hall as the “master” of still life in “modern times,” adopted a new motif in his work. Lance replaced the plain woven mats that created the foundation for his still life compositions in the 1840s (as in The Summer Gift (1848; Tate), at right) with more luxurious materials, such as brightly colored silks, rich floral embroidery, and elaborately patterned carpets. It is unclear what motivated this change, although it is likely that Lance became more familiar with seventeenth-century Dutch art during this period, for example, Willem Kalf’s Still Life with an Oriental Rug (early 1660s, Ashmoleum Museum, Oxford).

George Lance, “Interior of a Drawing Room Containing Portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Forbes and Mr. McCullough,” 1835, private collection.

In addition, an earlier Lance painting suggests another possible origin of this motif: Interior of a Drawing Room Containing Portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Forbes and Mr. McCullough (1835). William Forbes was Lance’s patron and neighbor in Camberwell in the early 1830s, and Lance’s own A Fisherman Mending his Net (c. 1830, private collection) is hanging above Forbes’s head in the drawing room, while the painting above Mrs. Forbes may be Fruit, Nautilus Shell, etc (1832, untraced), also painted by Lance. Forbes’s drawing room gives us a sense of the intimate ease of the display; several gold frames form a nimbus of sorts around Mrs. Forbes’ head as she casually rests her arm on another painting resting on the sofa beside her. The sunlight shining through window balances the bright light emanating from the landscape hanging over the fireplace, behind Mr. McCullough. Perhaps he has brought the print portfolio, propped against the table in the foreground, for viewing and discussion.

In fact, the print portfolio draws our attention to the textiles in the room, as the eye moves from the bright red table covering to the billowing white curtain and the Turkish rug that covers the drawing room floor. Moreover, the sofa upon which Mrs. Forbes sits is draped with a brightly colored and patterned woven cloth. In Lance’s Still Life with Fruit and Chalice and Goblet, a similar textile, with its pattern of stylized red pomegranates and yellow motif against a bright blue ground, is itself a form of artistic reference. It resembles a “Holbein Carpet,” a term for Turkish rugs incorporating powerful geometric forms, so called because they appeared prominently in paintings by Hans Holbein, such as in his The Ambassadors (1533; National Gallery, London). The market for “Holbein Carpets” flourished in the early nineteenth century, with designs imitating those of fifteenth century carpets like the kind featured in Holbein’s paintings. Is Lance showing us a historical carpet or a contemporary one? While sixteenth century Anatolian carpets like the kind favored by Holbein developed a pattern over the entire field of the carpet, the nineteenth century “Holbein Carpets” usually featured a “close-up” of the a historical design, an example of the melding of art and industry.

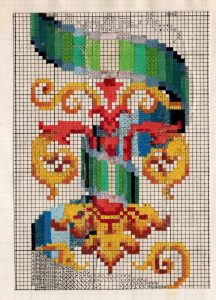

At the same time, the carpet bears a striking resemblance to another type of product: a Berlin wool-work carpet. As discussed in Barbara Morris’s Victorian Embroidery and Molly G. Proctor’s Victorian Canvas Work: Berlin Wool Work, the name pays tribute to the German city where a print seller published colored designs for needlework on gridded paper. Whereas most needlework previously was free-form design or pattern transfer, Berlin wool-work introduced the regularity and transferability of the grid to embroidery. On the one hand, this technique mimicked the practice of “squaring up” paintings for enlarging, copying or translating onto printing plate. On the other hand, the introduction of geometric regularity to embroidery allied it to industrial processes that relied upon rote and consistency. A picture or design would be divided into a grid and transferred to a coarse canvas or the canvas could be printed with the design. The patterns were prepared by men and the coloring instructions were created by girls on “point paper,” a pattern paper with ruled lines. A coding system evolved, but it was not standardized and could vary depending on manufacturer, to help embroiderers translate the color correctly. A dot in a square could mean pale, while a “V” could mean “very dark.”

Carpets were popular projects, as the coarse canvas and thick wool used in Berlin work meant that an expensive piece of home furnishings could be made quickly out of durable material. Lance oversaw the creation of a notable carpet of this kind: the “Ladies Carpet” presented to Queen Victoria at the Great Exhibition of 1851 after having been shown at the Society of Arts in 1850. The design came from the architect J. W. Papworth, son of the architect and designer John Buonarotti Papworth, at the suggestion of W. B. Simpson, who stated “a carpet should be made by ladies to prove the possibility of equaling the looms of the Continent.” Lance was one of the artists called upon to approve of the design, and he served on the committee. Papworth painted the design as one picture, and then cut it into 150 squares measuring two feet by two feet, one for each contributor. When joined together, they formed a carpet of thirty feet x twenty feet. The current whereabouts of this carpet are unknown.

In Novel Craft, Talia Schaffer described the mid-Victorian “craft paradigm,” the ways in which domestic handicraft was interwoven with the consumer economy—the industrial enabled the handmade. Yet, as Schaffer points out, the transition from handicraft to manufactured object resulted in a number of “uneven compromises.” At the Great Exhibition, “handmade” carpet gift to Queen Victoria—the “Ladies Carpet”—appeared in the same category as machine-made lace as “Industrial work” or “ornamental industry.” As Róisín Quinn-Lautrefin has noted, this type of embroidery “bridged the gap” between home and factory. According to the Art Journal, the Queen’s carpet demonstrated “a large amount of industrial perseverance.” Upon the presentation of the “Ladies Carpet,” the spokeswoman, a Miss Lawrence, declared the economic potential of such industry: “it is hoped that it illustrates an elegant branch of British industry and taste, and that it develops a source of manufacture which may afford employment to many, especially to those on whom the hand of adversity has been laid.”

Henry Courtney Selous, “The Opening of the Great Exhibition by Queen Victoria on 1 May 1851,” c. 1851-2, V&A.

According to design reform advocate and commentator Ralph Wornum, the “Ladies Carpet” fared better than most even though it still followed “thoroughly wrong principles of design . . . crowded with flowers and scroll-work in high relief.” Queen Victoria gave it her stamp (or stomp) of approval when she stood upon the carpet to open the Great Exhibition on May 1, 1851, as memorialized in Henry Courtney Selous’s painting The Opening of the Great Exhibition by Queen Victoria on 1 May 1851 (1851-2, V&A). Perhaps it was this first-hand experience with the Berlin wool-work carpet that inspired George Lance to rethink the textiles featured in his still life paintings. By 1855, with Still Life with Fruit and Chalice and Goblet, Lance had woven his signature into the carpet upon which the fruit rests, claiming both the painting and the carpet as the product of his art.

Lance’s interest in Berlin wool-work is unusual, as commentators usually gendered the practice as “feminine.” Pamela Gerrish Nunn has noted that the contemporary discourse of needlework portrayed it as more fitting to the imitative capabilities of female artistic expression. As she notes, for satirical journals like Punch, “bourgeois needlework’s mindlessness, its rote character, its dependence on the unthinking, imitative hand as opposed to the imaginative, inventive faculty which in fine art harnessed manual dexterity to the expression of an idea, were undeniable facts.” How do we reconcile this judgement with the longstanding tradition of copying in artistic training? Would practice in needlework be conducive to the fine art of painting? As she argues, “through embroidery women trained their hands and eyes, became attentive to the smallest details, refined their color sense, and mastered a large repertoire of motifs and compositional formulas.” Such skills would prove useful to the still life painter as well, a fact perhaps recognized by Lance with his woven signature.