Majolica Mania: Majolica in Three Paintings

This month, we are delighted to feature by post by Dr. Jo Briggs, Jennie Walters Delano Associate Curator of 18th– and 19th-Century Art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. Her exploration of majolica draws on research jointly undertaken by staff at the Bard Graduate Center in New York and the Walters Art Museum for an exhibition and three-volume publication titled Majolica Mania: Transatlantic Pottery in England and the United States, 1850–1915.

In March 1856, at a meeting of the Society of Arts in London, the critic John Ruskin was moved to express “astonishment” that the headmaster of the Government School of Art in Birmingham, who should in theory have been a proponent of the use of flat ornamentation on domestic objects, had just spoken “with exultation” of the “success in imitation of Palissy ware” by the Staffordshire firm of Minton & Co.

imitator of Bernard Palissy, Ornamental Platter with Pond Life, c, 1600-1700?, The Walters Art Museum.

Ruskin argued that “if appearance of projection was wrong on a carpet, real projection must be wrong on a dish … [and] of all the useless dishes that were ever invented, Palissy’s were the most so . . . if we were not to be allowed to have flowers on our carpets, why were we to be allowed vipers on our plates?” This outburst was part of a larger discussion of “Recent Progress in Design, as Applied to Manufactures.” Minton’s Palissy ware, or majolica as it is now more usually known, a lead-glazed molded earthenware, was first shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851, an event arranged largely through the efforts of Prince Albert and Henry Cole. Herbert Minton’s close friendship with Cole, who as vice-president of the Society of Arts chaired the March 1856 meeting, meant that, despite Ruskin’s bafflement, majolica became central to government backed design reform in Britain.

The clearest expression of Cole’s enthusiasm for majolica can be found in interiors at the Victoria & Albert (formerly South Kensington) Museum, where the glorious majolica tiled Central Refreshment Room, opened in 1868, continues to serve its original function. In the decades that followed, majolica became a global success, used mostly in the dining room and conservatory or garden. It sold at a wide variety of price-points and referenced an eclectic variety of styles. However, beginning in around 1900, legislation against the high levels of lead used in the ceramic’s glaze, which was toxic to workers, and changing perceptions of high Victorian design meant that majolica fell from favor; in the 1930s the Victoria & Albert Museum redistributed many of its holdings. Three paintings of domestic interiors register the gradual, yet dramatic, shift in the perception of majolica in the second half of the 19th century.

James Roberts, “Queen Victoria’s Birthday Table at Osborne, 24 May 1856, 1856. Royal Collection Trust.

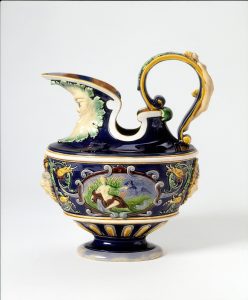

In 1856, the year that saw the exchange at the Society of Arts quoted above, James Roberts was commissioned to paint a watercolor to record Queen Victoria’s “birthday table” – a display of luxurious gifts she had received for her thirty-seventh birthday. The artist depicted the table at Osborne House decorated with flowers; the flags above commemorated the end of the Crimean War. At the center of the display hung Franz Xaver Winterhalter’s depiction of three of Victoria’s children: Princess Louise, Prince Arthur, and Prince Leopold. On the floor to the right of the composition, tucked behind a low partition, a majolica jardiniere and underplate can be seen, decorated with passion flowers and manufactured by Minton & Co. Other gifts, seen on the table, included a painted fan, jewelry, and porcelain. The queen acquired a number of majolica items from the firm in the 1850s, but the most important royal commission in majolica came from Prince Albert in 1858. Working with the architect and sculptor, John Thomas, Minton & Co. decorated the interior of the Royal Dairy at Frogmore House in Windsor Home Park.

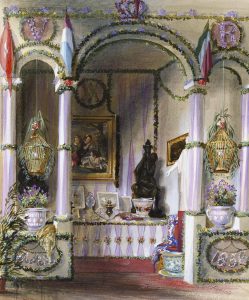

Nancy A. Sabine Pasley, “Interior with Couple Playing Cards,” c. 1887-91, The Geffrye Museum of the Home, London.

Around three decades later, a painting by Nancy Adair Sabine Pasley recorded how majolica was integrated into what was likely her own upper-middle class home. To the right on a table and holding a palm, a deep blue Minton & Co. jardiniere can be seen. The ceramics arranged around the mantle, the segmented ebonized mirror, green and yellow color scheme, dado, and the woman’s dress, which lacks the then fashionable bustle, all point to the “artistic” taste of this household, who have clearly absorbed the design edicts of the Aesthetic Movement. The links between this movement and Cole’s efforts to reform industrial design are complex, but a preference for flat patterning was a point of intersection. Although majolica typically strayed from these principles, as noted by Ruskin, the combination of Minton & Co.’s premier reputation, majolica’s presence at the South Kensington Museum, and the fact that the design of this particular jardiniere draws on a Chinese motif (elephants’ heads holding rings in their trunks), allowed it to harmonize with what appears to be a highly considered interior.

These first two images form a contrast with the American painter, Louis Charles Moeller’s, Spinning Yarns, which dates from around 1900. As a woman winds wool, a man entertains her with a funny story, hence the punning title of this work. At almost the center of the composition is a teapot manufactured by the firm of Wardle & Co. of Staffordshire, major exporters of low priced majolica to the United States, which, unusually for the time, was managed by a woman, Eliza Wardle, from her husband’s death in 1871 until her own death in 1889. Decorated partly in the distinctive pale blue glaze used be the firm, the design of this teapot was patented in 1881. On the teapot’s side, a fan forms the background for a stork in flight and a branch of blossom, reflecting the craze for Japanese motifs that was part of the Aesthetic Movement. Indeed, ceramics like the Wardle teapot show how the Aesthetic Movement influenced visual and material culture, especially in the United States. Although this interior does not indicate poverty, the artist has carefully included a number of elements that suggest unpretentious comfort, rather than fashion. Each element included by Moeller gives context for the viewer’s interpretation of his figures. The striped wallpaper and marble fire surround evoke the mid-19th century. On the mantle is a candlestick, book, and simple clock, alongside more decorative items, but no large mirror. Could majolica’s inclusion here suggest that it was becoming equated with an older generation? That mid-19th-century innovations were now the preserve of parents and grandparents? These were certainly the associations that were to accrue around majolica as the 20th century progressed.

Of course, if I had chosen different images, a different story of majolica could emerge. The Wardle teapot also featured in another painting by Moeller, titled The Tea Party, dating from 1905. The first two paintings discussed here are documentary in nature, while the third tells a humorous story. A teapot manufactured by Minton & Co. majolica would have had different connotations from one made by Wardle & Co, even in 1900, when the taste for majolica was declining. Nevertheless, these three images provide a fascinating insight into the story of majolica, and its integration into a range of 19th-century homes.