Material cultures of the interior

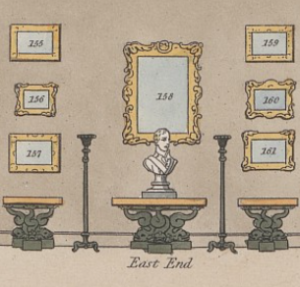

Detail of a view of the Old Gallery at Cleveland House. John Roffe (engr.), Old Gallery, in William Young Ottley, Engravings of the Most Noble the Marquis of Stafford’s Collection of Pictures in London (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, 1818), 61 cm. Digital image courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut

This blog is about the display of art in the domestic interior. When this project began, our posts tended to focus on the ‘art’ aspect of the brief we set for ourselves. Longtime readers may have noticed that more recently, the project has opened out somewhat, as the ‘interior’ becomes an equal partner with ‘art’ when considering display. Take for example, my own research on the interior of Cleveland House, a private townhouse that was, in the early nineteenth century, transformed into an art gallery by its aristocratic owners. For the past two centuries, most people thinking about the gallery did so mostly through the lens of the extraordinarily important collection of art that was exhibited there, and for good reason. Assembled by the Duke of Bridgewater and his nephews, the collection abounded with Old Master paintings by artists like Raphael, Titian, Claude Lorrain, Poussin, and the Carracci, artists whose works were highly sought after but not easily acquired in Britain prior to the French Revolution. But recently I have been thinking more and more about all of the other objects that were in the gallery. Pictures were surrounded by gilded frames, which could reflect light from the hundreds of oil lamps and chandeliers that illuminated the gallery at night. Mirrors, flower arrangements, and tables laden with food also enlivened its spaces.

Over the past year or two we have featured a number of posts that test the boundaries between art history and other disciplines. In January, Kate Retford wrote about the conversation piece, and how her work trying to understand these eighteenth-century images led her to thinking about the many other items of decor that appear in these pictures. The month before, I wrote the latest installment in an ongoing series we have written about Christmas decorations in historic interiors. (An article expanded from some of the earlier posts in the series will be published as a print piece forthcoming in 2021.) Last summer, Jo Briggs wrote about majolica and its role in interiors in the late ninteenth century, and last winter, Morna O’Neill about Berlin wool work.

As we think about the display of art in these broader contexts, we can learn much from the study of material culture and historians in many other fields. Going back to 1982, Neil McKendrick, John Brewer, and J.H. Plumb’s The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth-Century England illuminated how figures like Matthew Boulton and Josiah Wedgwood harnessed industry to art and design, creating objects for the interior. Over the past decade, a range of documentary series produced for TV have brought the scholarship in this field to a general audience–series like Lucy Worsley’s If Walls Could Talk and Amanda Vickery’s At Home with the Georgians (available in the US via Acorn TV). There are now several new podcasts produced by the next generation of scholars looking to share the latest scholarship about material culture. Sew What? by Isabella Rosner, launched in May and features discussions of a range of issues relating to textile history. Since its debut March 4, The Travelling Sisterhood of Art Historians podcast has so far included discussions of textiles, ceramics, and glass. And finally (for now), the recently-lauched podcast companion to Netflix series Bridgerton, includes historian Hannah Greig as one of its hosts. The series delves into the behind-the-scenes minutiae of making the show, and the first episode dives into the sets and locations that helped construct the world of aristocratic Regency London.