Conference: The Evolving House Museum

On June 18-19 I’ll be representing Home Subjects at a conference titled “The Evolving House Museum”—a roster of speakers and registration information are available at the link—which concerns the past, present, and future of art museums formed from buildings that once served as private dwellings. Amongst the best examples are The Frick Collection in New York, The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino California, or the Wallace Collection in London and the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris. Yet, conference organizers Margaret Iacono and Esmée Quodbach note, the success of these outstanding house museums can obscure the difficulty that less prominent examples face in attracting audiences and maintaining adequate funding.

Questions about houses, domestic interiors, and the display of art in those interiors are the core of what interests us here at Home Subjects, and we have returned to the interplay between these related fields of enquiry repeatedly over the years. House museums, especially the particularly grand ones like the examples named above, set fine art in the context of monumental-scale domestic architecture, displayed alongside furniture and objets d’art that purport to transport the viewer into interiors that were once ‘private’. Of course, many if not all of these houses were built with display in mind from the start. In 1806 the Marquess of Stafford, one of Great Britain’s richest landowners, opened a gallery at Cleveland House, his seventeenth-century London townhouse, to ‘the public’ one afternoon a week during the summer months. (I have written about my research on this gallery on Home Subjects before, here and here.) It became one of London’s most sought-after locations for looking at art, and specifically, at the famed examples of continental Old Master painting the gallery held. Early in its life, connoisseurs, artists, and journalists looked to museums as a comparison for the type of space that Cleveland House represented, some calling it the ‘Louvre of London.’ Because Cleveland House opened 18 years before the National Gallery in London was established, this nickname hints at the possibility that the house and the gallery it continued might be able to fulfill the role of a public museum.

At the time, the question of just where Londoners could go to look at continental Old Masters was quite pressing, especially in the wake of the founding of the Musée du Louvre to which Cleveland House was occasionally compared. In the early nineteenth century London was still conspicuously devoid of the sort of public, urban venues for the display of Old Masters—sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italian and French paintings that figures like Sir Joshua Reynolds, President of the Royal Academy, had celebrated as the models to which young British artists should aspire—that had accumulated in Europe over the course of the eighteenth century. Even before the Louvre came into being, the Capitoline Museum in Rome, the Uffizi in Florence, and the Belvedere in Vienna offered spaces where members of the public could look at art in eighteenth century Europe. A few of the grandest country house collections, such as Petworth, Wilton, or Burghley House, were accessible to tourists, but many connoisseurs and artists wanted a similar collection in the capital city, where as Reynolds once put it, they could be “seen by foreigners, so as to impress them with an adequate idea of the riches in virtu which the nation contains.”

Cleveland House seemed poised to fill this role. The house contained a large group of Italian and French masterpieces, including works by Raphael, Titian, Poussin, Claude, the Carracci, and many more, from the collection of the Duc d’Orléans, the head of the cadet branch of the French Royal family. The “Orleans Collection”, as it came to be known in Britain, had been one of the greatest in eighteenth-century Europe. Around 1790 it was broken up and subsequently brought in pieces to London for sale, where they entered the ownership of the Marquess of Stafford’s family. The renown of the Orleans pictures was an important motivating factor for the marquess to open the gallery; the pictures had famously been on display to the public at the Palais Royal in Paris for most of the eighteenth century, and exhibitions of the Orleans pictures in a variety of London venues at the time of their sale had whetted the appetite of the public to see what were now former French royal treasures. Especially during a period of war with France, the exhibition of these pictures in a British private house could be regarded as an act of cultural dominance over a longstanding enemy, and fulfilling the promise of an institution of ‘national’ import even as it remained ensconced in a private dwelling.

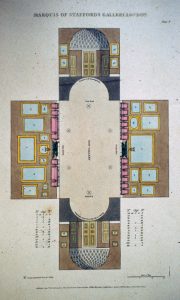

The “New Gallery” at Cleveland House, in William Young Ottley, Engravings of the Most Noble the Marquis of Stafford’s Collection of Pictures in London, arranged according to Schools, and in Chronological Order, with Remarks on Each Picture (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1818)

In order to display these pictures to their best advantage, the gallery was designed in order to adapt the emerging signs of public-facing “Museum”-ness in its design, such as skylighting and Greco-Roman architecture. The collection was arranged according to National Schools. Yet, despite these efforts, Cleveland House never became a museum. Instead, after a few decades of prominence on the London art scene, Cleveland House was demolished and a new house, Bridgewater House, was erected in its place. Like its predecessor, Bridgewater House contained a large gallery for the display of the collection to the public, but subsequent generations were reluctant to continue the tradition. The gallery at Bridgewater House slowly faded from view as other public art galleries and museums accrued in Britain’s urban centers. Eventually many of the most important pictures in the collection were placed on permanent loan to the Scottish National Gallery and the National Gallery in London, so that the pictures became to be displayed as museum objects while the house that had been built to display them went their separate ways. As a result, until relatively recently, Cleveland House had remained somewhat obscure while the houses of some of the Marquess of Stafford’s prominent contemporaries, like Sir John Soane and the Duke of Wellington, became musuems and, as a result, have remained much more prominent in the public eye. Soane had begun opening his house to architecture students sometime after 1813, and it became a public museum after his death in the 1830s; the Duke of Wellington’s son opened a “Museum Room” at Apsley House in 1853, and subsequently the house was given to the nation in 1943. Both remain popular tourist destinations, returning us to the theme of this conference. House museums offer a particular type of experience, but to continue thriving they will also need to continuously evolve (and in the case of the Soane, has done so; Morna O’Neill wrote about the “Opening Up the Soane” project in 2015.) Perhaps a look back at their precursors in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries may help shape a vision for their future.