Living in the Louvre

Today we have a post from Mia Laufer, who spoke at the Evolving House Museum conference featured in our last post.–ANR

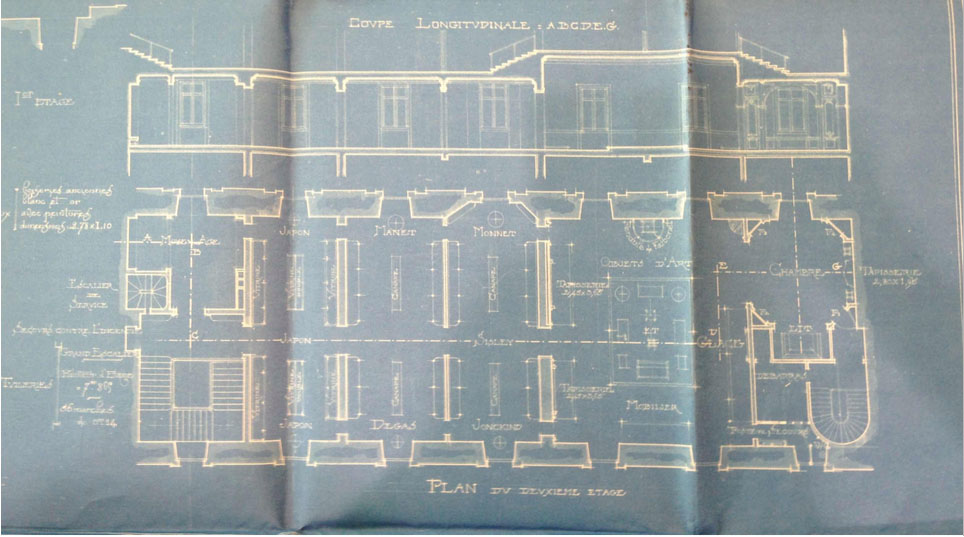

In 1911, Count Isaac de Camondo donated his bed to the Louvre. I’ve been studying Camondo’s collection and bequest for about seven years now, and I still can’t get over the strangeness of that fact, the incredible intimacy of it. To be fair, Camondo’s bed was an eighteenth-century antique and one of 750 objects in his bequest to the museum. Still, looking at architectural plans for the Camondo Galleries in the Louvre, it’s hard to miss the word lit in all caps given as much attention as Manet and Degas. An alcove specially designed for Camondo’s bed was written into the architectural plans in order to mimic the experience of the collector’s home, which suggests the importance of the domestic sphere and intimacy to both his collecting and his bequest.

Camondo and his family emigrated to France from the Ottomon Empire in 1869. His great-grandfather had established the family fortune in Istanbul, first with a real estate empire and later with an international bank. But by the 1860s, the family was looking for the kind of opportunities in business and high society that only Paris could provide. They moved to the fashionable rue Monceau in the eighth arrondissement and quickly integrated into French Jewish elite circles.

Isaac de Camondo began collecting in the 1880s to furnish his private apartment in his father’s new hôtel. He acquired entire rooms worth of eighteenth-century furniture at auction: tables, chests of drawers, chairs, a bed—even a chaise longue that belonged to Marie Antoinette. He also collected East Asian art, including lacquer work, sculpture, and ukiyo-e prints by Hokusai, Hiroshige, and Utamaro, as well as works of Medieval and Renaissance art. By the 1890s he began to pursue modern painting, with a focus on Impressionism—particularly art by Edgar Degas, whose pictures of the café, racetrack, and Opera echoed his favorite pastimes as a wealthy man about town.

Camondo was also an active member of several arts patronage groups, including the Société des Amis du Luxembourg and the Société des Amis du Louvre. Through these committees, he became an important voice in the Parisian art world and close friends with several curators at the Louvre, including Gaston Migeon, Émile Molinier, and Carle Dreyfus, often inviting them for lavish dinners at his home on Sundays.

“Galerie du Louvre” from “Album de 38 photographies du 82 rue de Champs-Élysées, chez Isaac de Camondo” c. 1910. Paris, Les Arts décoratifs, archives du musée Nissim de Camondo, 1146

Camondo began publicly discussing his intention to leave his collection to the French state in the mid-1890s. He donated parts of his collection in usufruct in 1897, 1903, and 1906, and the remainder upon his death in 1911. Camondo included two key conditions to his bequest. The collection had to be accepted in its entirety and be displayed together in a gallery bearing his name for fifty years. His cousin, Moïse de Camondo, acted as executor of his will and worked with Gaston Migeon and Victor-Auguste Blavette, the museum’s architect, to finalize the presentation of the collection, which opened to the public in 1914. (Moïse de Camondo was a brilliant collector in his own right. If you’re curious about the family, check out James McAuley’s recent book The House of Fragile Things, Edmund de Waal’s book of imagined letters to Moïse Letters to Camondo and his upcoming exhibition at the family’s house museum in Paris this fall.)

Even before the bequest was formally accepted, press reports stated that the Camondo Galleries would be arranged to reproduce the arrangement in Camondo’s apartment. His will did not stipulate how his bequest should be arranged, but in light of the many years spent preparing for the donation and his close friendship with Migeon, there can be no doubt that the two men discussed how it should be displayed. The museum decided to use a suite of rooms that would appear somewhat independent, in order to create the illusion of a private apartment—an innovation that was audacious for the Louvre at this time. The curators were eager to explore new modes of displaying art, and wanted to “avoid as much as possible appearing too much like a museum.” (By 1914 there were a few rare examples in Paris of museums that offered an intimate view of an interior, including the Musée Gustave Moreau, which opened in 1903, and the Musée Jacquemart-André, which opened in 1913. Camondo’s collection formed the first “period rooms” in the Louvre.)

There was some irony to the curators’ pursuit: they were trying to avoid making the galleries look too much like a museum by mimicking Camondo’s home, which he had organized during his lifetime to mimic a museum. According to his friend Gabriel Astruc, Camondo’s apartment was “installed for his collection such as the Amsterdam Museum is for its Rembrandts.” After his first donation to the Louvre was accepted in 1897, Camondo began calling the room in his home where those works were displayed the “galerie du Louvre.” His decision to construct a gallery within his home of art already donated to the state and refer to it in this way, suggests a kind of play-acting at living in the Louvre. It suggests a profound desire to not only be connected with but deeply integrated into French cultural patrimony and heritage. This desire for an intimate connection between collector and museum extended to the final design of the Camondo Galleries in the Louvre. The areas that were most faithfully translated were those that clearly evoked the domestic sphere. Camondo’s bed was tucked in an alcove, just as it had been in his apartment; his dishes were placed in glass cabinets as they had been in his home.

Sitting room in the Camondo Galleries at the Louvre, 1934. Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais.

While some celebrated the bequest as a generous gift to the state, critics railed against the audacity of creating a “Camondo Museum” in the heart of French collections. But from the beginning Camondo knew that for his donation to be accepted there would be some negotiation between his individual identity as a collector and the collective identity inherent in a national museum. This dynamic was written into the conditions stipulated in his will: that the collection should remain together in a special room with his name—but only for fifty years. Perhaps one of the most basic motivations for a collector to keep their collection intact after their death is the wish for immortality—that something they created will live on with their name after they are gone. While Camondo could have easily opened a private museum that would have continued in perpetuity, he gave up that semblance of immortality for fifty years of living in the Louvre.