The Mezzotint

I learned recently that Mark Gatiss’ brand-new adaptation of one of my favorite ghost stories, “The Mezzotint” by M.R. James, is coming on December 24 to British audiences via the BBC and to American audiences via Britbox. The BBC made a number of adaptations of James’ stories under the title “A Ghost Story for Christmas” in the 1970s, and revived the practice in 2005. This is the third adaptation Gatiss has made of one of James’ stories for the series, beginning with “The Tractate Middoth” in 2013 and continuing with “Martin’s Close” in 2019. In the United States, Britbox will also be releasing much of this back catalogue of seasonal ghost stories to coincide with the holiday. I’ve written for Home Subjects before about the British tradition of telling ghost stories at Christmas, and the release of “The Mezzotint” and the rest of the BBC’s adaptations of James’ stories seems to offer a perfect occasion to extend these reflections on the confluence of ghosts and hauntings, interiors and exteriors.

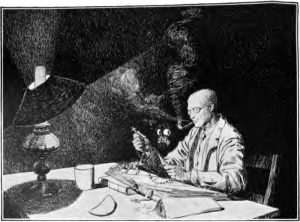

James McBryde, “A Hand Like the Hand in that Picture,” in Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, 1904. Illustration appears opposite p. 26, in the story “Canon Alberic’s Scrap Book.” Wikimedia Commons.

“The Mezzotint,” which is available to read at this link, was first published in Ghost Stories of an Antiquary in 1904. In the preface, James indicates that he had written the story sometime in the 1890s to read aloud to friends at King’s College, Cambridge, where he was a Don in Medieval Literature. “The Mezzotint” of the title refers to an undated print from the early nineteenth century, described by one character as having “quite a feeling of the romantic period,” encountered by the story’s protagonist, a curator named Mr Williams who is in the process of acquiring English topographical drawings and engravings for a fictional museum in Cambridge. As I sat down to write, I realized that I can say little without spoiling the story’s unsettling essence. Suffice it to say, over the course of a few pages, “The Mezzotint” ranges over a set of preoccupations that appear in many of James’ stories: the mysterious aura that attaches to places over long stretches of time, the incompleteness of historical documents we find in the archive, and the malevolence that often attends the decline of those who once enjoyed a more privileged social position. Ghost Stories of an Antiquary contains several illustrations, but none that correspond directly to “The Mezzotint”; James asked one of his group of friends from Cambridge, an artist named James McBryde, to illustrate the stories, but McBryde died after completing only four. McBryde’s illustration for the story “Canon Alberic’s Scrap Book” captures the unnerving confluence of antiquarian research and supernatural menace that is the hallmark of James’ oeuvre.

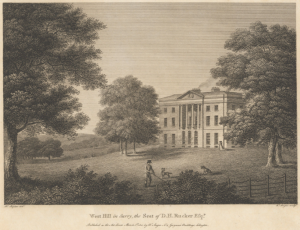

Print made by William Angus, 1752–1821, British, after Humphrey Repton, 1752–1818, British, Published by William Angus, 1752–1821, British, West Hill in Surrey, the Seat of D. H. Rucker Esqr., 1810, Etching and line engraving on moderately thick, slightly textured, cream wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.1159

We never see the titular mezzotint of James’ story, but are told it is a conventional country house view from the early nineteenth century, possibly something like William Angus’ etching of West Hill in Surrey made in 1810. James’ characters, perplexed as to why a print dealer had placed an unusually high price on what appeared to be a run-of-the-mill country house view, would have done well to note the choice of medium used by the print’s maker. Mezzotint tended to be used for atmospheric landscape scenes, or views of tumbledown cottages and romantic ruins. It was not a common choice for country house views, which tended to be rendered in the clear, legible black and white tones of etching and line engraving like those used in Angus’ view. Mezzotint emphasizes the ambiguities and grays of its subject, and is emblematic of the engima surrounding the origins and subject of the print at the center of James’ story.

That mezzotint was embraced by landscape artists is also significant to this interpretation of the story. By their nature, country house prints often included sweeping views of the landscapes in which they were situated. In “The Mezzotint”, it is implied that the house takes up a relatively large percentage of the picture space, as in Angus’ view of West Hill, but many views consisted mainly of expansive landscape with the house pictured in the far distance. The interplay between the house and the landscape in which it sits is an important theme in “The Mezzotint”, for reasons readers may discover for themselves.

William Holman Hunt (1827-1910). The Haunted Manor, 1849. Purchased 1967 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T00932

But it put me in mind of another image from the nineteenth century that places the relationships between interior and exterior at a similar intersection of natural and supernatural forces, William Holman Hunt’s The Haunted Manor, painted in 1849. Hunt’s painting depicts the overgrown banks of a stream below a disused mill, the water running through discarded stones amongst which iris have begun to spread. In the upper right hand corner, a large house looms, the sunset reflecting eerily on its many windows. Though the circumstances surrounding its making are uncertain, it is believed that Hunt’s painting may have been inspired by a trip to Ewell, in Surrey in 1847. The picture represents the uncanny precision of many of the early works of Hunt and his frequent companion John Everett Millais, who may have accompanied Hunt on this occasion. The use of the motif of the house (an element that was likely added later), and the claim that it is haunted, lend an air of disquiet to what would otherwise appear as a tranquil slice of suburban life. It frames the landscape as a manifestation of haunting in the natural world, which was common in James’ work. While many of his stories revolve specifically around the haunting of houses, churches, rooms, and other interior spaces, he is also masterly at exploring the role of landscape in capturing tragedies of the past which manifest in haunting. “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad,” finds spiritual disturbance along an lonely beach in winter and in an overgrown graveyard. “The Ash Tree” is set at a country manor house; the tree of the title grows immediately adjacent to a bedroom window, the presences that inhabit it threaten to invade the interior. Likewise, “The Mezzotint” invites readers to reflect on these themes by allowing the exterior and the (unseen) interior of the house pictured in the print to interpenetrate one another in unexpected ways, lending the story its lingering atmosphere of dread.