Sleeping Beauty and the Domestic Interior

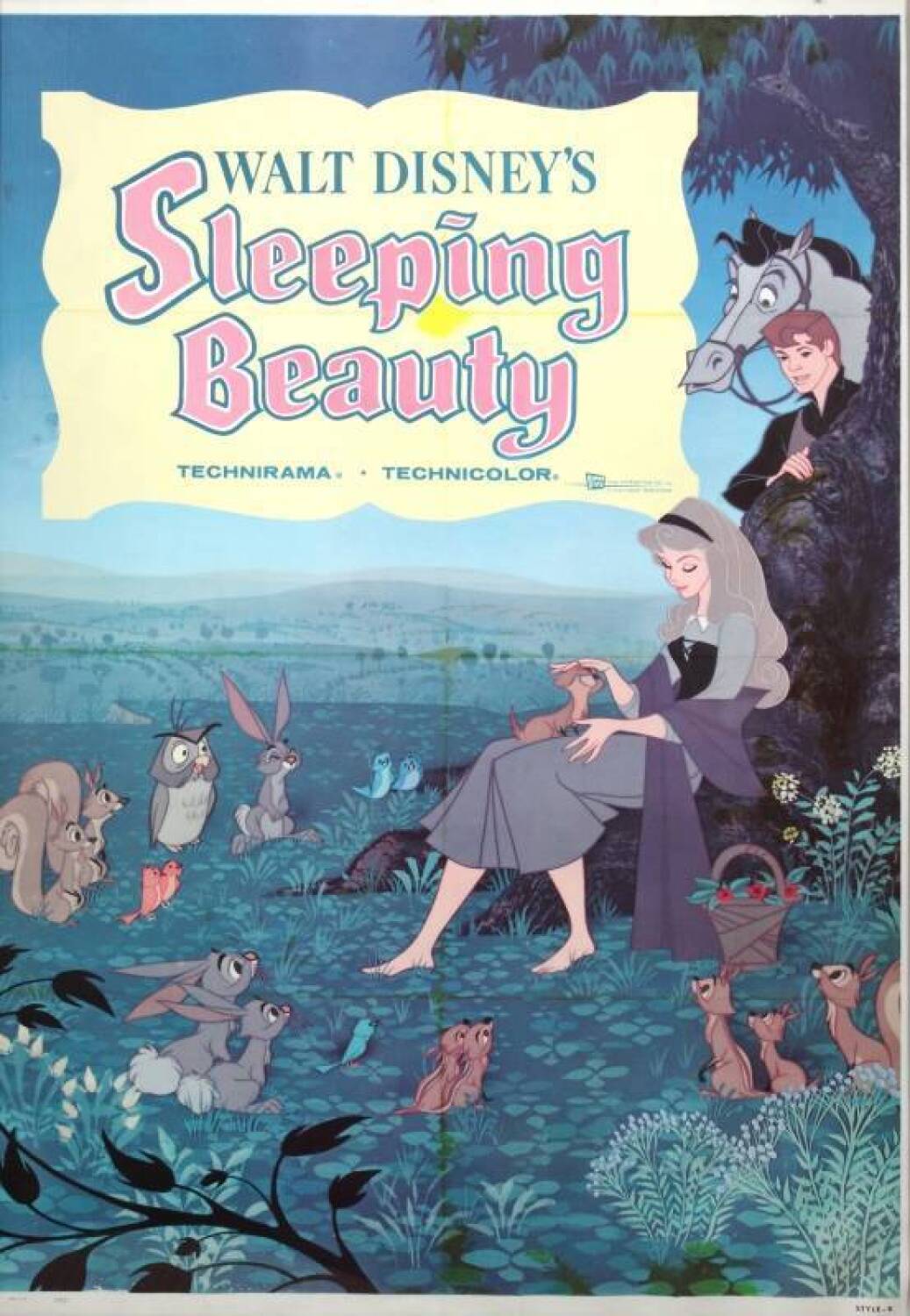

The recent exhibition Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art featured a fascinating section on Sleeping Beauty (1959) and its “Francophile” aesthetic. The exhibition brought The Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries (1495-1505; also known as the Unicorn Tapestries) from the Met Cloister’s collection together with original art from the film to highlight the medieval sources that inspired Disney artist Eyvind Earle and his colleagues. By following this theme, the exhibition highlighted the rendering of the natural world, especially in the early scenes with Princess Aurora such as “Once Upon a Dream.”

The exhibition explores this medieval source material in relation to Charles Perrault’s story “The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood,” recounted in his Histoires ou contes du temps passé (1697). The first part of Perrault’s story (wherein a princess, under a curse, falls asleep for a hundred years until awakened by a prince) became the standard version of the story throughout the nineteenth century. Inspiring Walt Disney acknowledges the wide popularity of this and other tales by featuring nineteenth century illustrated editions in the exhibition, including work by Arthur Rackham. Yet Rackham’s illustrations, like Disney’s films, do not spend much time on describing the castle’s interior or decorations, focusing instead on the sinister vitality of the natural world. For the decorative interior of Sleeping Beauty, we can turn to the illustrations of Walter Crane.

Fairy tales, which Crane knew well from his work as an illustrator, often rely on personification. The eponymous “Sleeping Beauty” of the familiar fairy tale, for example, is both a woman named Beauty and a representation of beauty as a concept. Crane’s illustrated The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood (1876) as well as the wallpaper design that followed in 1879, and he returned to the story in 1905 with the cabinet painting The Briar Rose. In these versions, the story of Sleeping Beauty and her eventual awakening set within the domestic interior goes so far as to suggest the wholesale transformation of art.

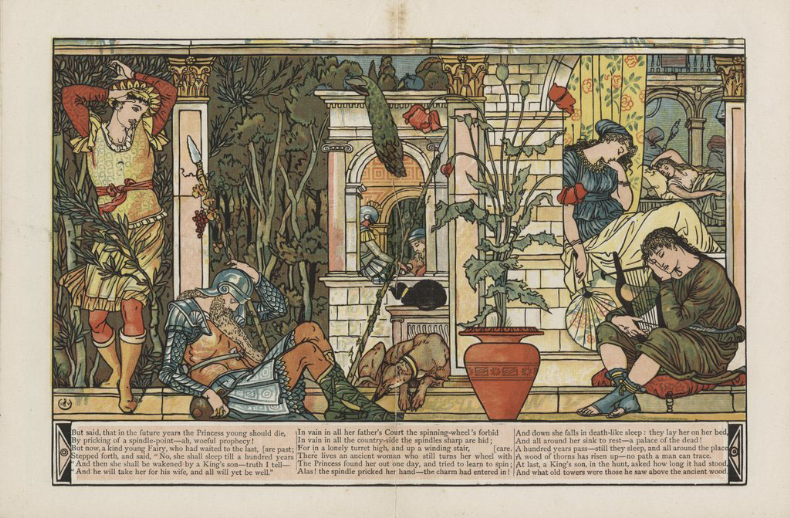

Walter Crane, centerfold illustration to The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1876), Beinecke Library, Yale University.

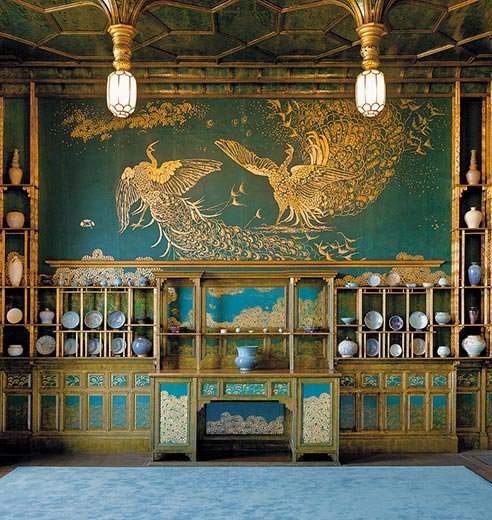

“Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room,” interior decorative art created by James McNeill Whistler and Thomas Jeckyll, translocated to the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, 1876-7.

The centerfold illustration for The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood furthers the identification of “Beauty” with “Art” through the inclusion of a peacock in the illustration. The peacock—in particular, the tail feathers—came to symbolize the Aesthetic movement. Yet this icon of the exotic made famous (or infamous) by Whistler’s Peacock Room was also a traditional symbol of eternal life and, in early Christian tradition, resurrection. In The Bases of Design, Crane would later fuse the peacock’s Aesthetic overtones with its more traditional associations to suggest that it symbolized the eternal quality of art. Like the other slumbering creatures in the illustration, the peacock will awake alongside the princess. In this way, we can understand the political import of Sleeping Beauty as the slumber and awakening of art: she (art) falls asleep under capitalism but will awake to socialism. Throughout his career, Crane returned to the example of Sleeping Beauty as a potent metaphor for intertwined nature of art and politics, in particular the state of art in a capitalist society. For example, he began his 1892 essay “The English Revival of Decorative Art” with “the sense of beauty” who, “like the enchanted princess in the wood, seems liable, both in communities and individuals, to periods of hypnotism.” As he explains, “these periods of slumber or suspended animation, are not, however, free from distorted dreams . . . until the hour of awakening comes.”

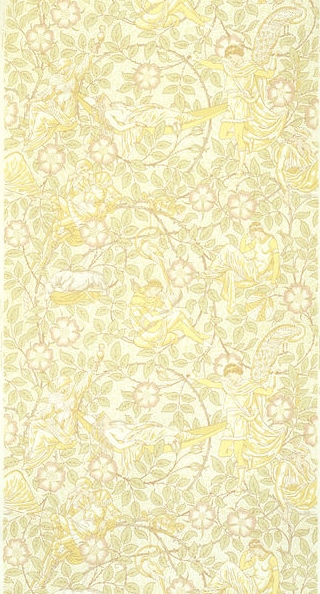

This design transforms figures familiar from Crane’s illustrations into units of ornament. He first suggested the decorative capacity of the body to communicate meaning in a wallpaper design after his Sleeping Beauty illustration from 1879 (V&A). The energetic swirl of the rose branch that structures the wallpaper is a direct quotation from Crane’s illustration, identical to the pattern on the curtain that shelters the sleeping heroine. Crane places figures from his illustration within this branch structure and orders them against this backdrop: we find Sleeping Beauty herself, her courtiers (including her aged father, the King), the old crone at her spinning wheel, and even the sleeping hound. The tail of the peacock, another reference to the illustration, falls just over the shoulder of the prince, making it appear at first glance that the prince has wings. The victorious prince emerges from the thicket to wake the sleeping princess, and the repeat of the wallpaper pattern imagines the event as a perpetual recurrence.

When he finally painted the story of Sleeping Beauty in 1905, Crane empowered the viewer to enact the renewal of art. He placed three tempera panels within a richly decorated cabinet. He titled this piece The Briar Rose, when he exhibited it at the first exhibition of the Society of Painters in Tempera. In this version, the artist enhanced his allegory of the awakening of beauty by using gesso to highlight details on the exterior doors of the cabinet that suggest the long passage of time: stems, leaves, thorns, and hourglass globes. These details also refer to an earlier moment in the narrative, as one-hundred years must pass before Beauty can be awakened. The empty hourglass indicates that it is now time to break through the thicket of thorns and make way to the castle tower in the background. The visitor/viewer is invited to activate the narrative by opening the cabinet doors. Once open, the cabinet reveals a vision of the sleeping princess.

Walter Crane, “The Briar Rose,” (closed), 1905, oil and tempera on panel, 1905. Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow.

Edward Burne-Jones painted perhaps the best known treatment of the Sleeping Beauty theme in nineteenth century art: the four-painting series entitled The Briar Rose installed in Buscot Park: The Briar Wood, The Council Chamber, The Garden Court, and The Rose Bower (1870–1890; Faringdon Collection, Buscot Park, Oxfordshire). Burne-Jones kept the princess asleep in order “to leave all afterwards to the invention and imagination of the people, and to tell them no more.” This vision inspired the French critic Robert de la Sizeranne to read a moral in the paintings about the inefficacy of agitation: they suggest that “the most righteous cause, the truest ideas, the most necessary reforms, cannot rise triumphant, however bravely we may fight for them, before the time fixed by the mysterious decree of Higher Powers.” William Morris’s verses, written especially for the paintings, seem to reinforce this reading, as Morris describes “the fateful slumber” of the princess who waits for “the fated hand,” and the day “when fate shall take her chain away.” The thorny thicket depicted in Burne-Jones’s Briar Rose series suggests that resistance is useless until the appropriate time.

Walter Crane, “The Briar Rose,” (open), 1905, oil and tempera on panel, 1905. Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow.

Crane’s placement of the Briar Rose story within a cabinet does more than just involve the viewer: it creates a political statement that unfolds before his or her eyes. By opening the cabinet, the viewer not only transforms the narrative but also, transforms themselves. Once the doors are opened, the viewer sees three tempera panels that contain a narrative progressing from left to right: to the left, the priest and the king are here accompanied by a jester who is also asleep. At the center, the knight approaches to awaken the princess, while on the right, beauty—a metonymy for art—has already awakened: the ladies-in-waiting stretch themselves after their long sleep and resume making their crafts. The lion and rose (English national symbols) on the prince’s cloak are part of a motif that is also found on the embroidery frame. Could this be the “English Revival of Decorative Art” that Crane sought in his essay? Her bed rests upon a rug decorated with a border of clovers and fylfots. The priest and the knight are contained within a colorless hallway—but rampant in Beauty’s boudoir, meanwhile, is decoration, its organic energy as powerful as that which makes the vines grow outside her door.

In The Briar Rose, beauty’s awakening is twofold: personification and representation. The placement of the later painting in a cabinet, however, speaks to shifting artistic and political currents at the end of the nineteenth century. The elaborately decorated piece of furniture suggests Crane’s engagement with the crafted domestic object espoused by the Arts and Crafts movement, in particular the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, from 1888 onward. The cabinet recalls the personal, portable altarpiece of the middle ages. The painting’s aesthetic is that of the private chapel rather than the cathedral altarpiece. Perhaps the failure of socialism to cohere as a mass public movement in the 1890s led Crane to focus on the individual in 1905.

By placing The Briar Rose in a cabinet, Crane gives physical form to the capacity of allegory to “speak other.” Crane’s crafted object is the ultimate real allegory. One image, with a particular meaning, appears on the surface of the work while a hidden image—and a different narrative—lurks within. By hiding the story, the cabinet acknowledges the subversive potential of Sleeping Beauty’s tale.