The Inca Empire on Parlor Walls

NB: Anna Ficek is a PhD candidate in Art History at the CUNY Graduate Center. Today’s post is drawn from her research for her dissertation, which examines the phenomenon of Les Incas in eighteenth-century French culture. –ANR

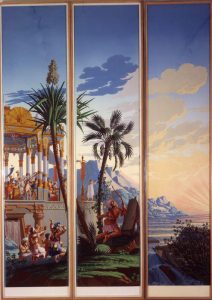

Ötlingen, a centuries-old German village, just 15 kilometers outside of Basel, is not a place one would think to look for a luxury nineteenth-century French wallpaper. In the upstairs dining room of the Café Inka, between daily specials, steaming cappuccinos, and slices of black forest cake, is one of the few extant examples of Dufour et Leroy’s 1818 panoramic wallpaper, Les Incas ou le Destruction de l’Empire du Pérou (1777). Based on Jean-François Marmontel’s novel, Dufour et Leroy’s wallpaper brought exotic places and colonial fantasies into the home. The lush tropical foliage, ornate classical columns, and the vaguely ‘exotic’ costumes of the Inca who populate the panorama immediately betray that the artist had never been to Peru, nor was he concerned with representing truth. The Peru we see in Les Incas is a manufactured fantasy designed to enthrall the burgeoning upper-middle class in the early nineteenth century.

Dufour et Leroy, « Les Incas » panoramic wallpaper (detail), 1818, Museumslandschaft Hessen, Kassel, LDTM 430.

Marmontel’s Les Incas is a half-fictional, half-philosophical novel. It begins with a description of the Incan worship of the sun, through the celebration of the autumnal equinox. The heroine, the Virgin of the Sun, Cora, is introduced as a reluctant devotee. At the setting of the sun, Aztec refugees arrive in Peru, demanding protection from the Spanish. The Cacique, Orizombo, recounts the violence of the conquistadors to the horrified Inca. When the Spanish arrive in Cusco, Alonso—one of the conquistadors—meets Cora. He frees her from her vow as a Virgin of the Sun, falls in love with her, and ultimately, seduces her. The novel ends in tragedy. Alonso is killed and Cora, mad with grief, dies on his grave while giving birth to their stillborn child. Edited for a bourgeois interior, the wallpapers depict neither the colonial violence nor the tragic ending to Cora and Alonso’s love story.

Produced by France’s leading wallpaper manufacturer in the early nineteenth century, the panoramic wallpaper was a particularly extravagant and sumptuous ornament to the interiors of grand homes. In 1830, the wholesale price for a complete set of Dufour et Leroy’s wallpapers was between 100 and 375 francs-or, and substantially more for the retail customer. As a point of reference, the average rate for a day-laborer in the early nineteenth century was approximately 2 francs-or per day. The laborious process of producing these objects and the specific skillset needed to install them necessitated such a high price. The wallpapers were printed by hand on individual paper strips using hand-carved wooden printing blocks. The colors were layered one on top of the other, in meticulous order. The Les Incas wallpaper was printed using more than 2,000 wooden printing blocks, and 83 unique colors. In order to achieve the desired effect, specially-trained wallpaperers were required to install each panorama.

Dufour et Leroy, « Les Incas » panoramic wallpaper (detail), 1826, Musée du Nouveau Monde, La Rochelle, MNM.1982.3.3.

Dufour et Leroy, « Les Incas » panoramic wallpaper (detail), 1826, Musée du Nouveau Monde, La Rochelle, MNM.1982.3.3a.

The wallpaper in Cafe Inka was rediscovered in 1986 by Hans-Georg Koger, whose family have owned the building for over a century. At the time, the room was being used as a storage space, and crowded furniture and boxes blocked the wallpaper from view. Its existence had long been forgotten, and sadly, so has the history of how and why it was installed in Ötlingen. Over the course of the preceding decades, the room had been used as a venue for village meetings and other events, a tavern, an inn, and even for weddings. The Cafe Inka wallpaper is not the only Les Incas wallpaper in Germany. Another example is located in Warendorf, in the former home of Dr. Franz Josef Katzenberger (1767-1836), and the Deutsches tapetenmuseum in Kassel has fourteen of the wallpaper panels in its collection. Three other museums own some of the Les Incas wallpaper panels: the Musée des Arts Decoratifs (Paris), the Musée du Nouveau Monde (La Rochelle), and the Victoria and Albert Museum (London).

On the other side of the Atlantic, Les Incas wallpapers can be found in historic homes that dot the Eastern seaboard. Following the American Revolution, French hand-printed wallpapers were incredibly popular amongst the elite of the fledgling United States. The vogue for French interior decoration was no doubt inflected by political sentiments, as French troops supplied and fought alongside Washington’s Army. An example of the wallpaper is in the Sitting Room at the Residence of the Governor of Pennsylvania in Harrisburg. Another is in Providence, Rhode Island in the former home of Eliza Ward, the daughter of John Brown (one of the founders of Brown University). The King Caesar House, in Duxbury, Massachusetts, the former home of one of New England’s wealthiest shipbuilders, also boasts a set of the Inca panoramic wallpapers. Through its multiple owners, the King Caesar wallpapers were removed and reapplied in different rooms around the house. Of the 25 panels, 14 originals remain while the other 11 are hand-painted facsimiles. Another titan of New England industry, the shipping magnate Robert “King” Hooper, also had the wallpapers installed in his Danvers, Massachusetts home. Now known as ‘The Lindens’, the home was disassembled in 1933, and rebuilt in the Kalorama Heights neighborhood of Washington, DC in 1935-1938.

Dufour et Leroy « Les Incas » single wallpaper length, 1826, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, E.811-1939

Dufour et Leroy’s Les Incas is a late example of péruvienophilie, a specific form of exoticism prevalent in France in the second half of the eighteenth century. Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire and Rousseau framed the Inca as an ‘ideal’ empire. In his discussions on Peru, Voltaire exclaimed: “The Inca lack only our vices to be equal in every respect to the European.” Voltaire (rightfully) vilifies the Spanish conquest without demanding any introspection regarding the expanding French Empire. Les Incas—the novel and the wallpapers—demonstrate the complex relationship ‘Enlightened’ Europe had with other countries’ colonies.

The Inca wallpapers at the Malouinière de la Ville-Bague, just outside of the French port city of Saint-Malo, demonstrate this uneasy relationship all too well. Built by the ship-owning Eon family in 1715, the extravagant home was paid for by their international maritime interests, namely in the Spanish port of Cádiz. Given that Cádiz was one of the key Spanish colonial ports, it is quite probable that the Malouinière was built on profits extracted from colonial Peru. The wallpaper was installed by marquis de Cheffontaines and his wife following their return from exile during the Revolution in a bid to rehabilitate the Malouinière’s (and the family’s) lost grandeur. A more on-the-nose colonial tension is palpable at the Quinta del Duque del Arco, near Madrid, where the luxurious wallpaper lines a grand oval sitting room. Installed on the eve of the Latin American Wars of Independence by the Spanish Royal Family, the sanitized and beautified conquest of the Inca brought an uncomfortable fantasy into a royal home made rich by the exploitation of those very colonies. The Spanish Royal Family had a long-standing relationship with the Quinta del Duque del Arco. Following the fall of the Franco Dictatorship, the room served as the office of the then-prince Don Juan Carlos in the 1970s.

The McKim, Mead & White-designed Percy Rivington Pyne House on Park Avenue and East 68th Street in New York City is a relatively unassuming Upper-East-Side mansion. The building now houses the Americas Society, an organization that aims to foster dialogue throughout the Americas and promotes the diverse cultural heritages of the Americas. On the second floor, in a room usually closed to the public due to conservation concerns, Les Incas is a treasure shared with the Society’s most important visitors. Dufour et Leroy’s Incas make fitting decor for an organization that aims to make us consider how we define “America”. The Americas Society Les Incas encapsulates the various subtexts of the wallpaper’s two-century-long history and the heritage it assumed from Marmontel’s novel; a historical tool, an opulent panorama, and a complex but beautiful lens through which we reconsider how we define places, nations, and concepts that appear simple, but are as manifold as the wallpaper itself.