Reflections on “The Essex Serpent,” A William Morris Society Conversation

Editors note: We are delighted to feature a guest post this month, courtesy of the William Morris Society in the US. Some of us may have read “The Essex Serpent” (2016) by Sarah Perry or watched the recent television adaption, available in the US through Apple+. Set in 1893, the novel tells the story of a young widow Cora Seaborne and her retreat to coastal Essex, where she meets the local vicar William Ransome and his wife Stella. An amateur naturalist, Cora is looking for the origins of a magical sea beast that she things might be a previously undiscovered species. Costume design by Jane Petrie and set design by Alice Normington were extensively covered in the fashion and entertainment press. WMS-US board members Sarah Mead Leonard, Brandiann Molby, and Anna Wager discussed the production over zoom in winter 2022. This conversation first appeared in ‘Useful and Beautiful,’ the WMS-US’s newsletter for Spring 2023. This conversation is likely more of interest to those who have seen or read “The Essex Serpent” but they did try to avoid spoilers! –MO

The Essex Serpent, a television series based on the novel by Sarah Perry, is a story about science, belief, and feeling at the margins of respectable Victorian culture. Cora, a rich young widow and brilliant amateur paleontologist, comes to Essex in search of fossils, and follows rumors of a strange beast out into the marshes. Cora is convinced the serpent is a living fossil, a survival of an earlier evolutionary period, but the villagers around her are just as convinced that it is a supernatural beast, a judgment from God. And amongst this external drama of opposing beliefs and real danger, Cora is also at the heart of a maelstrom of deep, complex, and passionate relationships in both Essex and London.

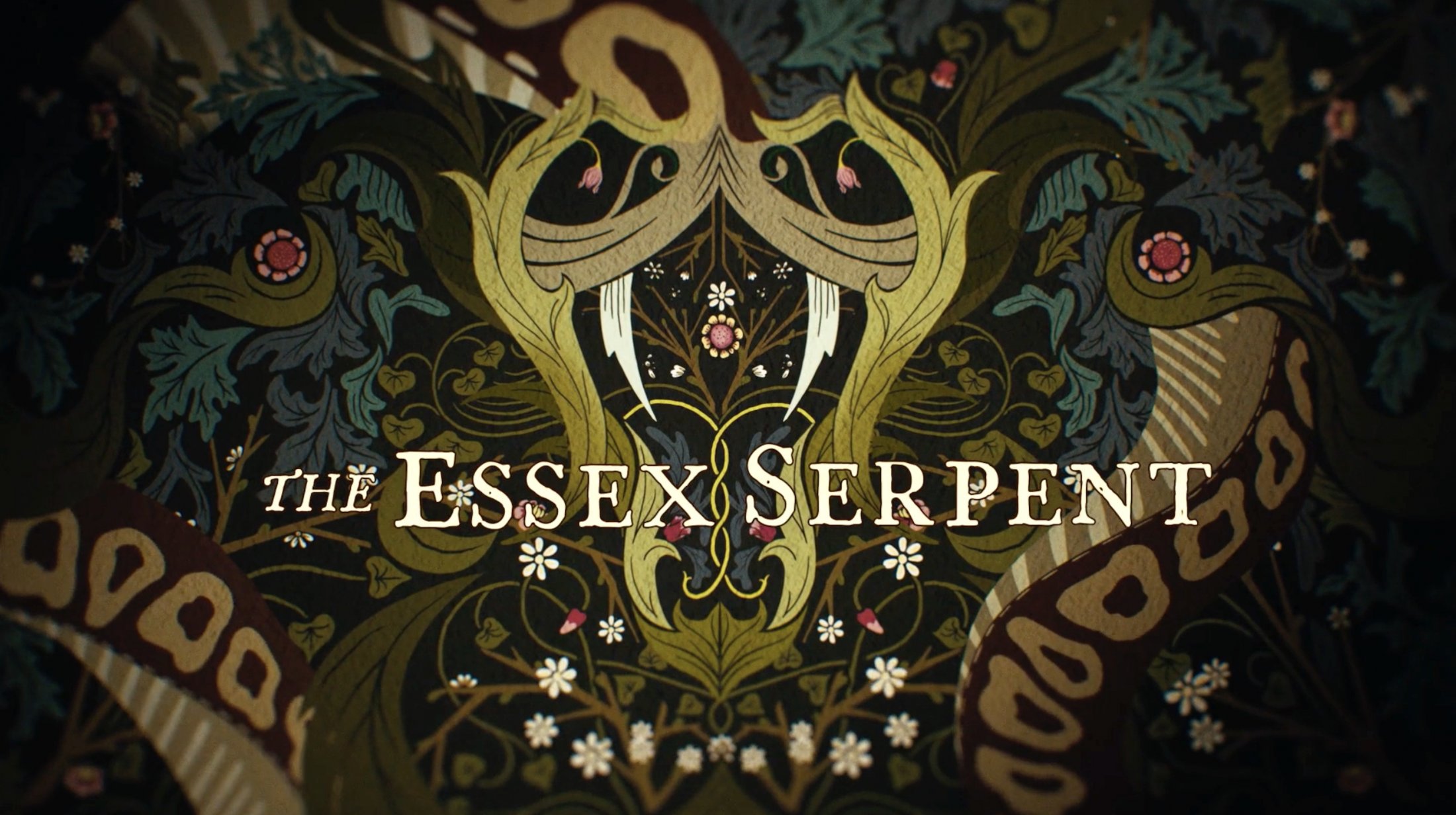

Brandiann Molby: One of the things that I wanted to be sure to talk about was the look of the show. Because this is for U&B and we have amongst us the Every Morris (a social media project documenting every Morris & Co. wallpaper and printed fabric) expert. So, tell us about the title sequence, Sarah.

Sarah Mead Leonard: The title sequence. I was trying to think about it yesterday, and I’ve been trying to think about it since I started watching it. The title sequence is also taken from the cover of the book, which is based on a Morris–well, really they’re both based on [John Henry] Dearle designs. Actually, I need to go through it frame by frame, because the sequence uses a few designs. Blackthorn shows up, which is also a Dearle, and then also Morris’s wallpaper Honeysuckle.

This is something that I keep on trying to hash out in my own mind, because Morris designs, and some [similar] designs keep showing up in shows with a certain vibe. I’m trying to figure out and have not managed to articulate to myself yet why there’s an underlying old-fashioned creepiness that they’re able to evoke. They show up in a lot of haunted houses, and I think it’s partially just that Victoriana and horror go hand in hand a lot. But there’s also something innate, I think, and it really stood out to me with this one, because the show is about nature, and about the weirdness of nature, and then they layer [the design] with the heart and the toad, which makes it even more intertwined with that, which I find very interesting. But, there is something I think about the darkness and density of the designs, which has an, if not uncanniness, then discomfort to it. Is that an innate thing? Is that an aesthetic that something about us in the 2020s finds really uncomfortable?

Anna Wager: I hesitate to use the word organic when we talk about pattern design, but it feels like there’s more of a sinuousness to Morris’s wallpaper in a way that does lend it to movement, and to bringing a kind of creepy movement into a space, even though I have never thought of them as creepy, particularly. But why Morris and not another Victorian wallpaper? Maybe designers just use Morris because they’re the most famous ones at this point, or the most famous type.

Brandiann Molby: Also the best!

Anna Wager: Yes, the best! I was thinking about Anna Tendler’s artwork, do you know her photography? She did this series of photos over the last year called Rooms in the First House, and it’s just her in her New York mansion up in the Catskills, with Morris wallpaper and other papers of the period, and these minimalist haunted scenes that she stages with her body. But I can’t tell if the design is what is heightening the creepiness.

Brandiann Molby: I want to defend Morris a bit here. I don’t think there’s anything inherently creepy about [the designs]. I think any time you’re doing any kind of design, [what matters is] what you do with it, because you can put the sweetest teddy bear of all time in the middle of this haunted house scene, and all of a sudden it’s terrifying. But I think you’re right. It is the sense of movement. It is the nature, because horror is supposed to be like a perversion or distortion of something that we otherwise think of as wholesome, or that helps create this effect along with the Victoriana.

Sarah Mead Leonard: I really like the movement in the credits. I like seeing things where people articulate and add movement. There was a game that the V&A did with pattern, and it used Morris and Co. patterns with movement in it. There’s something kind of strange and wonderful in seeing them in motion and seeing them with living creatures in them.

Brandiann Molby: Do you think then maybe we could say that the title sequence captures some of that tension in the show between the beauty of nature and the unsettling-ness of it? Is it natural? Is it really there?

Sarah Mead Leonard: Yeah, I think so. And there’s also something in the mix between aesthetic and beauty. You see that with Cora and her crazy gowns, and coming out of this London world, and her house. But then you also get it with Stella, who wears Artistic Dress, which is also very interesting. Given that she’s a country vicar’s wife, she’s very much this aesthetic figure, both with her fixation on color, but also with the way that she dresses and the aesthetic around her. And then you’ve got these two women, and also Luke, with his embroidered waistcoats and all of his Bohemian friends. But then they’re all in this other setting, and the contrast between [them]—. I didn’t manage to fully finish that thought, but that happens in the show, and that also happens in the credits. The toad in the middle of Blackthorn is what rises in my mind, and the kind of lumpen muddiness of the toad in the middle of a Dearle pattern is the opposite of that rather than Cora in the marshes. Also the marshes are interesting to talk about, because the Essex marshes are one of Morris’s native landscapes and a place that he really loved. But I don’t think he [thought of the marshes] in the way they’re depicted in the show. So I just jumped to three different things.

Brandiann Molby: I think you’re right that the costumes and the sets highlight the extent to which everyone is out of place. I love your description of the vicarage in the marshes, and then Cora’s husband’s house. Because it’s not her taste, she’s not at home there, for all the reasons, and it’s this lacquered like—

Anna Wager: Japonisme.

Brandiann Molby: Yes, Japonisme.

Sarah Mead Leonard: Red lacquered.

Anna Wager: It’s oppressive—

Brandiann Molby: —Tightly controlled and artificial.

Tom Hiddleston as Will and Claire Danes as Cora in a production still from “The Essex Serpent,” courtesy of Apple+.

Anna Wager: You’re so right that she doesn’t fit— none of them do. And I was reading something today with the costume designer that was saying basically, Tom Hiddleston’s clothing is cut from the same fabric that the other villagers are wearing, but it’s cut in a totally different way. He looks like he’s trying to fit in, and he’s not quite getting it. And Stella definitely doesn’t fit. And then Cora comes in with her hair, which is that wild color, and her clothing being so completely different, like her cowboy hat! Sarah and I were texting about her sweater dress because we both want one, and it’s just so different from what other people are wearing. Stella blends just because I think she’s more of a blend-able person, whereas when you actually look at the style of her clothing you’re like, “Oh, this is completely different from what anyone else here is wearing.”

Brandiann Molby: The way that their vicarage is decorated is gesturing towards the eclecticism of the Arts and Crafts movement, even if it’s not going full bore, and it’s not having the money poured into it that luxury clients are using. Her aesthetic dress at least, to use your word, blends with that eclecticism, even if it does stand out from the architecture of the place.

Sarah Mead Leonard: I remember from the book they’re not from there. Will, I think, came out of the university system, and they’ve settled there [in Essex], and they’ve committed there. And he particularly, like you said, with the costumes, is trying to fit in there. But that’s not their world. They come out of a world that’s more, well, not like Cora’s exactly, but it’s kind of equivalent; but they have rooted in this place.

Brandiann Molby: Cora has a dress—I don’t think she wears it in the country, but she wears it in London, and it’s got this herringbone or v-neck [striping] across the bodice in blue and red, and it’s right at the point [in the show] where she’s torn between town and country. Her house is red, or her husband’s house is red, and the country is blue. Stella is all about blue, and [Cora’s] son is obsessed with blue, and so here she is, like literally fifty-fifty, divided between these two spaces.

Anna Wager: I’m a sucker for any sort of media that kind of delves into places that are real and exist, but are also very mythical. Like anything related to Brittany; I was thinking of Portrait of a Lady on Fire while watching this. Or Cornwall, and Essex is doing something similar here. I was just on the Aran Islands, and there’s very much that kind of energy there too, where it’s real but it’s not, simultaneously, and that is always super fascinating to me.

A scene in the marsh, production still from “The Essex Serpent,” courtesy of https://locationmanagers.org/the-making-of-the-essex-serpent/.

Sarah Mead Leonard: That’s a really good point, because Essex you think of as a London suburb. This is a story you expect to be telling about Cornwall or about Wales—these kind of Celtic fringe mystical places. But again, going back to Morris’s thing with the Essex marshes, it is a weird landscape, I think. And it’s really easy to get lost. Because tidal landscapes like that shift and change, with the water coming in and out, and are so featureless. I don’t know if they filmed the show in Essex, but I feel like they did a really good job of capturing the landscape and the strangeness. During the scene where the boat is going out with Stella, there was a scene filmed from above with the water lapping at the marshy shores that was really beautiful and really strange, and also just muddy and brown and ugly at the same time.

Anna Wager: That’s super interesting, because then you think about people trying to root themselves there when it’s shifting around them. Stella’s such a sympathetic character, obviously because of the TB, also because she’s just very nice, and kind, and genuinely cares for Cora, and wants to be very supportive to her son and all of that. When you try and think of, how is she navigating this space again when she’s so different from other people there, and when she can’t even really get a handle on what the land around her is doing, that’s such a wildly isolating space to be in. It’s very, very evident. The landscape moves that much, even though it’s also there, and there are all these attempts to contain it and structure it, and they kind of work.

Brandiann Molby: It’s interesting, too, that the way that you are characterizing the landscape also connects with the faith and certainty tensions. Nobody can put a foothold in. You can’t navigate it all the time. It’s constantly shifting and altering around you, and people are trying to make sense of that. In that way, the landscape makes a lot of sense.

Sarah Mead Leonard: I think with those kind of traditional, fishing communities and stuff you do think of superstition and things being associated with those communities, because the sea is ever changing, and it’s an appropriate place to set it in more ways than one, because there is that kind of deep tradition which you also get in places like Cornwall, which is that kind of mystical ocean thing. But instead of being in the ocean, it’s a weird, muddy marsh.

Brandiann Molby: It gives narrative access to the fossils without having to set it on the Jurassic coast or Lyme Regis, or other places where the nineteenth century novels have already kind of been done.

Sarah Mead Leonard: The Essex earthquake was a real thing. They don’t mention it very often in the show. There’s more stuff about it in the book. And that’s why the ground has kind of shifted, and things have been revealed.

Anna Wager: It’s another destabilizing force.

Brandiann Molby: Well, thank you both for doing this.

Anna Wager: Yes!

Sarah Mead Leonard: I’m glad we finally got it together.