The many lives of Aynhoe Park

RH England, occupying the 17th century house called Aynho(e) Park, near Banbury, UK. Photo courtesy of RH.

It’s August, and we at Home Subjects are not immune to the charms of a little celebrity news and period property eye candy. In June a press release for the launch of RH (the furniture brand formerly known as Restoration Hardware)‘s first international location, RH England, caught our eye. The launch party included celebrity attendees Idris Elba (who also acted as DJ for the evening), Michelle Dockery (also known as Downton Abbey‘s imperious Lady Mary), and Regé-Jean Page of Bridgerton. That two of the three celebrities just named found fame on the international stage thanks to being cast in projects that used historic buildings and interiors to project a brand of “Englishness” that is situated firmly within the aesthetic universe of eighteenth and nineteenth-century art and design does not seem coincidental.

Quoting RH’s website may be the best way to explain what this venture is (or aspires to be). “A 400-year old landmark estate designed by preeminent British architect Sir John Soane, RH England is a celebration of history, design, food and wine. Reimagined and open to the public for the first time, the 73-acre, 60-room property seamlessly integrates RH Interiors, Contemporary, Modern and Outdoor collections with rare art, antiques and artifacts from across the globe. Explore historic gardens by iconic English landscape architect Capability Brown and enjoy three dining experiences – the Orangery, the Loggia and the Conservatory – as well as a Wine Lounge, Tea Salon and Juicery.”

In other words, the entire building and its grounds have been transformed into an RH showroom, a place to go explore collections of furniture, lighting, and home accessories, all available for sale, in the context of a grand country house set in an eighteenth century landscape. At the same time, to further entice visitors to make the trek, multiple dining venues have been incorporated into the property, serving generically upscale menus featuring ingredients like Wagyu beef and Petrossian caviar. Don’t forget the wine bar, tearoom, and juicery, all of which are photographed to show the venture’s mixing of old and new to best advantage. The “Tea Salon” boasts views over Capability Brown’s landscape, discreetly-lit towers displaying canisters of tea occupying the spaces between windows where Boulle cabinetry might have once stood.

Bottega Veneta Home Collection on view at the Palazzo Gallarati Scotti, Milan. Photo courtesy of Bottega Veneta.

Certainly, I am no expert in the logics of the international luxury brand market and in no position to comment on the business aspects of this project. Knowing how astronomically expensive these properties are to maintain–a problem that has attended many of their owners going back centuries–I am curious about the underlying business model. According to one writer who covers the business side of the interior design indusry, RH England marks a bid to transform “what was once a purveyor of knickknacks and antique doorknobs into a genuine luxury brand” of the stature akin to Hermès or Cartier. Other high-end design firms have experimented with using prestigious historic buildings as showrooms. To cite just one example, in 2015 Italian luxury brand Bottega Veneta launched its first home furnishings line with an installation in the 18th century Palazzo Gallarati Scotti in Milan, juxtaposing sleek contemporary designs with the building’s high coffered ceilings and frescoes by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

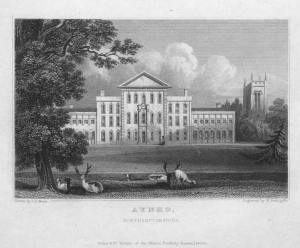

J.P. Neale, Aynho Park, from Jones’ Views of the Seast, Mansions, Castles, &c of Noblemen and Gentlemen in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland (London: 1829)

I would like to explore how this project fits into the narratives that we at Home Subjects have been interested in unpacking, especially the way in which the upper-class dwelling has always been a site that addresses both public and private concerns, is itself a economic engine despite constant attempts by aristocrats and other elites to distance themselves from the mechanisms of trade, and how the aesthetics of domesticity were adopted quite early as a marketing vehicle. (These links highlight just a few of the many previous posts on Home Subjects that address these issues.) RH England occupies a house known as Ayhnoe (also spelled Ayhno) Park. Ayhnoe Park was first built in approximately 1615 and underwent significant alternations later in the 17th century to repair damage sustained during the English Civil War. In 1707 the existing building was enlarged, and then renovated again at the turn of the 19th century by Sir John Soane, much of whose work is preserved in the current building.

Room featuring exhibition on Sir John Soane, one of the architects who created Ayhnoe Park as it now appears, at RH England. Photo courtesy of RH England.

RH partnered with Sir John Soane’s Museum, London to produce an exhibition to teach visitors more about the building’s architect. Looking back through time, Ayhnoe Park’s trajectory as a property offers a snapshot of a typical story of a 17th or 18th century English country house. The house had escaped the period of widespread demolition of such houses, which were generally too enormous and expensive to staff and maintain as a result of a confluence of circumstances during the first half of the twentieth century. Aynhoe Park had been owned by the Cartwright family since the 17th century, but a tragic auto accident in 1954 killed the current head of the Cartwright family and his only son/heir. The house was then acquired by an organization called the Country Houses Association, which, seeking to find alternative uses for it, converted most of the building into accommodations for retired people. Around 2008, Ayhnoe Park was sold to James and Sophie Perkins, who transformed the building into a high-end hotel and entertaining venue while simultaneously using it as a private residence and family home. RH bought the house from the Perkins’ in 2020.

Drawing Room at Aynhoe Park, photographed by Marianne Taylor. For more photographs of the interior visit https://mariannetaylor.co.uk/aynhoe-park-interiors/

James Perkins is a event promoter who is sometimes referred to as an “impresario,” and together the Perkins transformed the house into a venue which successfully attracted celebrity weddings and other celebrations, while also incorporating retail space to showcase James Perkins’ own furniture designs. James and Sophie Perkins decorated the house in an eclectic, stylish idiom combining Soane’s austere interiors with 1970s furniture, contemporary art and other assorted items collected hither and yon. Photographs of the interior by Marianne Taylor capture the whimisical decor such as that found in the Drawing Room, outfitted with mirrored pieces of furniture and spectacular “Feather Floor Lamp” (which is available for purchase).

Joseph Michael Gandy, Design for eating room, dated “Aynhoe Novr 5th 1799,” pen and sepia wash on laid paper, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

Taylor’s photography also captures, importantly, the subtle vaulting of Soane’s architecture. (Images of the interior are difficult to access, but it was also photographed by Paul Barker for Jeremy Musson’s The Drawing Room: English Country House Decoration in 2014.) After James and Sophie Perkins decided to move on, they sold the house’s entire contents at auction in January 2021, an event one magazine called the “sale of the century.”

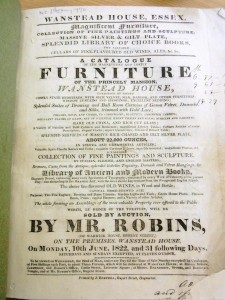

The reference to the “sale of the century” should offer a reminder that there have been many such sales, and that the use of the country house as a stage for selling a vision of aristocratic taste to the highest bidder is a longstanding tradition. Diana Davis wrote about the notorious Wanstead House sale of 1822 for for Home Subjects back in 2016, drawing attention to how in that case, the sale was both used as a moralistic tale about the wages of profligacy and as a marketing tool to offer prospective buyers a ready-made upper-class lifestyle. As Davis reminds us, in the Wanstead case, the sale still did not raise the funds needed to save the house and within a few years, it had been demolished.

View of the Fountain Court within the Western Cloister, with the additions made in June 1823 to convert it into a public refectory for the visitors. Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

“The Pavilion and the Lake in the Old Park,” in The Repository of Arts (August 1823). The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

The story of RH England also reminds me of my first published article, which explored the complicated mix of cultural signifers represented by the auction at Fonthill Abbey (which also took place in 1822). As I wrote in that article, Fonthill Abbey had a remarkable history, and had been filled with remarkable objects by its equally remarkable owner, William Beckford. Beckford found himself unable to keep the house after losing two of his Jamaican sugar plantations, which were one of his main sources of income, as the result of a legal dispute. The auction was cancelled at the last minute, and the house and contents were sold for the enormous sum of 330,000 pounds to John Farquhar, who had made his own enormous fortune in the gunpowder manufacture industry in India under Charles Cornwallis, then governor-general of Bengal. Even though Beckford’s auction never took place, the house and the collection had been transformed into a major tourist attraction. Catalogues for the sale were sold in London, Amsterdam, Brussels, and Paris, and thousands of tourists, only a small handful of whom would have had the wherewithal to buy, descended on Fonthill. Only about a year later, Farquhar mounted his own auction, to sell on some of Beckford’s collection and capitalize on the interest that had so recently turned Fonthill into a “nine days wonder.” Farquhar embraced the public’s impulse to turn a visit to Fonthill into a day out, complete with tour of the house and refreshments. These could be taken in a pavilion erected in the park which was inself noteworthy enough to be illustrated in the Repository of Arts. As the Repository‘s accompanying text noted, the presence of the pavilion enabled visitors to enjoy their day with “propriety and comfort” since refreshments “of the most simple or of the most luxurious kind” could be “reasonably purchased at all times.” In addition, a pop-up restaurant overseen by Mr. Dore of the White Lion in nearby Bath was installed in the Fountain Court of the Abbey, to further accommodate the crowds. Whether it is RH England’s Tea Salon, or one of the tea rooms at any of the National Trust’s properties, or at Fonthill’s Fountain Court in 1823, the tradition of going to see a country house and have a slice of cake is a beloved summer tradition, one on which RH clearly hopes to capitalize.