Living Pictures: Madame Tussauds at Warwick Castle

A “festive elf” poses in front of a copy of Van Dyck’s Portrait of Charles I and M. de Saint Antoine at Warwick Castle, image courtesy of FQ magazine.

We aim to be seasonal at Home Subjects, and I recently found myself contemplating how to address the festive season in this December post. In the past, we have written about museums and country houses that decorate for Christmas, and we were delighted to expand this exploration in an essay in Revisiting the Past in Museums and Historic Sites, edited by Anca I. Lasc, Andrew McClellan, and Änne Söll. At the same time, I was finding it difficult to come up with a new angle. As we have explored, many country houses wrestle with the balance between their goals of historic preservation and presentation and the enhanced commercial opportunity presented by Christmas visitors. I started to investigate country houses that are not part of the National Trust or English Heritage to see if any interesting case studies emerged. Were there properties that embraced the commercial? I remembered a long-ago visit to Warwick Castle that featured a waxwork figure of King Edward VII. As I began to learn more, I realized that Warwick Castle’s “Christmas at the Castle” is just one iteration of the commercial strategies undertaken by numerous Earls of Warwick and, more recently, Madame Tussauds and the Merlin Entertainment Group.

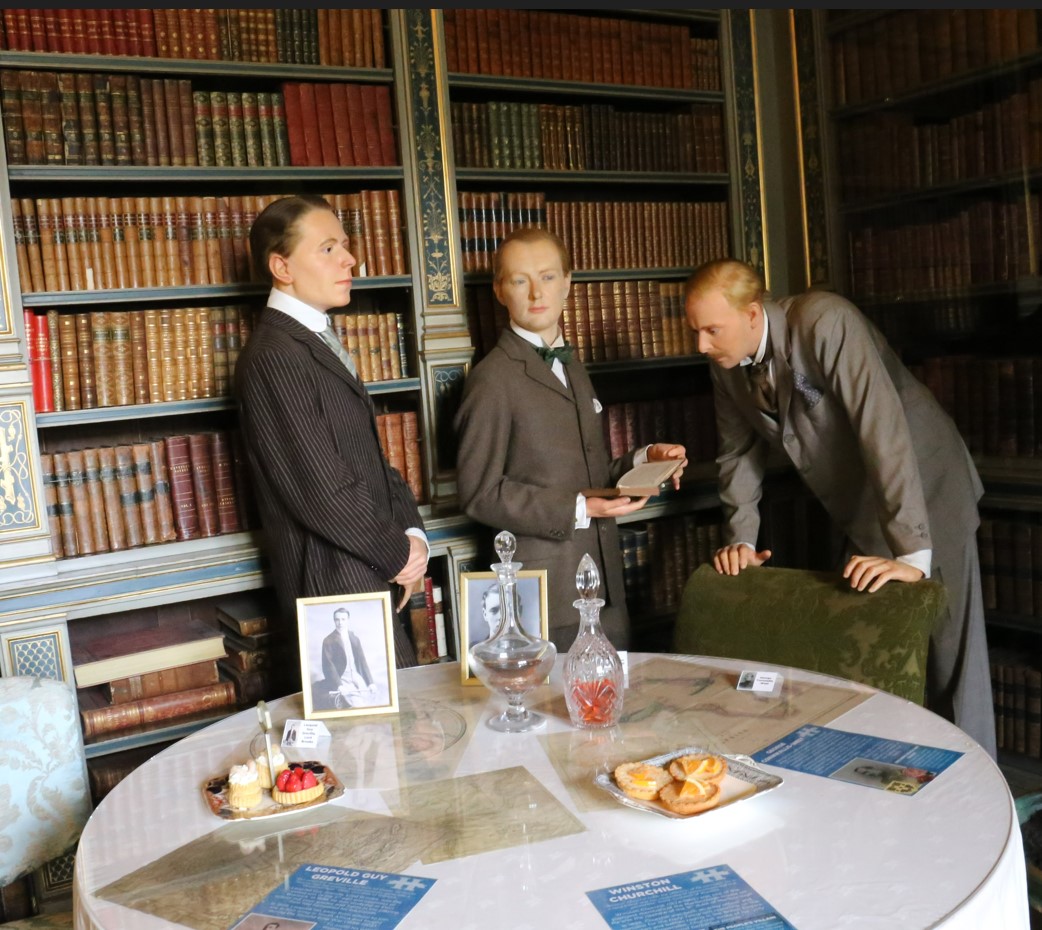

One of the groups of wax figures in the castle; Lord Brooke (left), a young Winston Churchill (center) and Spencer Cavendish (right). Visitor picture posted on Flickr.

Many visitors who comment on TripAdvisor are not kind to the interventions at Warwick Castle arranged by Madame Tussauds. (Previously spelled as Madame Tussaud’s, the apostrophe is no longer used). As one notes in 2012, “Visited here many years ago and it was interesting. Then Madame Tussaud’s took it over and turned it into . . . well, a wax museum tourist trap.” Although Madame Tussauds added the wax figures, Warwick Castle has operated as a tourist attraction since the eighteenth century, as chronicled by Martin Westwood, the former general manager there. While the castle was one of six established in England by William the Conqueror after 1068, its ownership moved in and out of the royal circle until 1604, when Sir Fulke Greville petitioned James I for ownership. He began the conversion of the site from a fortress to a mansion, a program that reached its peak in the mid-eighteenth century. The Greville family were granted the title of Earl of Warwick in 1759, thanks to a petition by Francis Greville, who became the first Earl. He added a state dining room in 1763 and hired Capability Brown to landscape the gardens. He also presciently commissioned Canaletto to paint five views of the castle in the 1740s. The second Earl of Warwick expanded the family’s art collection and commissioned the first inventory in 1809, expanding the fame of the castle as a destination for tourists. The housekeeper under the second Earl, one Maria Hume, is said to have saved the family from bankruptcy through her savings of £30,000, gleaned from tips given by grateful visitors for her tours of the castle.

Canaletto, Warwick Castle, 1748, Bequest of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 2019, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The castle remained open to visitors almost continuously from the 1760s. Yet it was only in 1967, when the 7th Earl of Warwick passed the estate to his son Lord Brooke, that the castle embraced its role as a tourist attraction. Lord Brooke worked with a firm to manage the castle, and new areas of the house opened to the public, such as the armory and the dungeon. Annual visitors reached 500,000 in 1978. Lord Brooke then sold the castle, and most of its contents, to Madame Tussauds. The sale was controversial: the headline for the 1996 obituary of David Robin Francis Guy Greville, the Eighth Earl of Warwick, in the New York Times reads: “Earl of Warwick, 61, Who Sold his Castle to Madame Tussauds.” As the Times notes, the family had long complained of inheritance taxes and realized that the castle had operated as a tourist attraction for years. In addition, before the sale to Tussauds, Lord Brooke had sold many of the celebrated works of art in the family’s collection, including the four iconic views of the castle painted by Canaletto. They are now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Thyssen-Bornemisza, the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery and the Yale Center for British Art. He also removed all furniture and decoration, including pictures, from the private apartments in the castle. Tussauds began a period of repair and investment focused on visitor services, and they also opened up new areas of the castle for tours, including the private apartments. According to H. T. Cooke, writing in the 1847, the private apartments were “not allowed to be inspected by the visitor,” so this added a new “upstairs/downstairs” frisson to the castle. Martin Westwood, who wrote about the program at Warwick Castle for Tourism Management in 1989, described Madame Tussauds philosophy: “we remain true in spirit and in context to the original resource.” This philosophy seems remarkably conscientious for a commercial entertainment venture. Yet the creation of The Royal Weekend Party 1898, the main “Tussauds” intervention from this period still on display today, reveals that “remaining true in spirit” is open to interpretation.

Tussauds decided to animate the private apartments and incorporate their brand into the castle by staging waxworks tableaux that tell the story of a visit by the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, to Warwick Castle in 1898. He was the guest of the Fifth Countess Frances Evelyn, known as Daisy, who often hosted society house parties that included important guests. (She would later be known as “the Red Countess” for her interest in socialism, a topic I had previously explored in an essay on her friendship with the artist Walter Crane). The twelve rooms of the private apartments were arranged with the original furniture (now on loan from Lord Brooke), and twenty-nine wax portraits of guests and servants. A visitor could find Daisy dressing in her boudoir, a maid running a bath, and gentlemen gathered in the drawing room. Publicity materials emphasized the accuracy of the scene, and reviews often point out that “every chair, table, bed and book in exactly the place it occupied exactly 100 years ago.”

The Countess of Warwick entertaining her guests in the Music Room. Visitor picture posted on Flickr.

Warwick Castle seems to be a singular instance of a historic property with an art collection that also features a waxwork installation. Yet as Richard Altick noted in his magisterial Shows of London (1978), displays of paintings, decorative objects, wax works, peep shows, panoramas, industrial processes, and mechanical inventions were a vital part of urban culture, and these exhibitions were often placed in dialogue with one another by artists, audiences, and social commentators. By the 1830s, when Madame Tussaud’s was established in Baker Street, she was buying works of art as part of the display or creating tableaux in relation to paintings. For example, Queen Victorian encouraged George Hayter to make a copy of his portrait of her in her coronation robes for display at Tussauds. This practice goes back to Madame Tussaud’s roots in France and her work with Philippe Curtius—he modeled the murdered revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat in his bath, and it is possible that Jacques-Louis David based the painting on the wax model due to the decay of Marat’s body.

The Duke of Wellington visiting the Effigy and Personal Relics of Napoleon (Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington) by James Scott, after Sir George Hayter mezzotint, published 1854, NPG, London.

In his The Romance of Madame Tussaud’s (1920), her son John Theodore Tussaud recalls that the Duke of Wellington visited the attraction to view their wax tableaux of the lying in state of Napoleon, an anecdote that inspired the painting of this encounter by George Hayter. As these examples suggest, waxworks were often perceived in relation to politics; Punch noted in 1846 that there was “a great Moral Lesson at Madame Tussaud’s:

The collection should also include specimens of the Irish peasantry, the hand loom weavers, and other starving portions of the population all in their characteristic tatters; and also the inmates of the various workhouses in the ignominious garb presented to them by the Poor Law. But this department of the Exhibition should be contained in a separate Chamber of Horrors and half a guinea should be charged for the benefit of the living originals.

The reference here to Tussauds infamous “Chamber of Horrors,” which began as a display of models of criminal and French Revolutionary heads, suggests the continuing political power of wax works. In the modern era, however, the displays at Madame Tussauds and other wax figure museums are more commonly associated with celebrities. Eagle-eyed visitors to Warwick Castle can see historical celebrities of a sort, such as Cecil Rhodes and Winston Churchill as members of the royal party.

Wax figures, along with mannequins, continue to be a popular, if contested, form of folk and ethnographic museum display. There is an element of this type of display at Warwick Castle, where the Kingmaker installation uses waxworks to animate the castle as a fortress and show Richard Neville the Earl of Warwick preparing for battle in 1471. As Mark B. Sandberg details in Living Pictures, Missing Persons: Mannequins, Museums, and Modernity the late nineteenth century was the moment when effigy culture combined with other technologies to “body forth a convincingly lifelike yet mobile body” (5). In their uncanny stillness, displays such as wax works were a pendant to the technological and mobilized body of the modern era. This approach gives new life, as it were, to the historical practice of artists working from mannequins or lay figures, as pictured in Edgar Degas’s portrait of Henri Michel-Lévy (1878, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon). Figures such as the one Degas depicts were usually near life-size (the Met has a lay figure in its collection that is five feet three inches tall). Lay figures could allow for a convincing (and affordable) arrangement of the human body with the guarantee of stillness for artistic study. Thomas Sully borrowed the coronation gown of Queen Victoria for a mannequin as he worked on his commemorative portrait of the young Queen in 1838. Mannequins are a regular feature of costume, dress, and armor displays, such as those at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

More recently, artists have turned to wax works as a subject and as a medium. In her Waxworlds series (1983-2000), Susan Wides photographed the “uncanny and claustrophobic” displays in wax museums to explore their shared qualities with the medium of photography. Many of these contemporary interventions rely upon the notion of the waxwork as “uncanny,” indebted to Sigmund Freud’s exploration of the ways in which something that is familiar can at the same time be strange and threatening. While the Edwardian royal party tableaux at Warwick Castle approach the uncanny through resemblance, they also flirt with the absurd. The maid is running a bath that will never be filled. The Countess of Warwick forever stands at the piano. Many of these rooms are hung with works of art that formed part of Lord Brooke’s collection. Photographs of the apartments make a fun guessing game: Is that a Lely? What about Kneller? These portraits of forebearers, along with “school of” Old Masters and smaller landscape paintings, function as historical props to the social scenes staged by the wax figures.

Christmas Banquet in the Great Hall at Warwick Castle, photograph from Group Leisure and Travel Magazine.

Warwick Castle is now owned and operated by Merlin Entertainments, which acquired the Tussauds brand in 2007. Current marketing for Warwick Castle prioritizes the medieval heritage of the site–complete with wax figures of knights–although The Royal Weekend Party 1898 remains listed as an attraction. While “Christmas at the Castle” can include a “Tournament Feast” with “live action entertainment from our Knights throughout the feast,” the waxworks in the private apartments remain in a perpetual Edwardian summer weekend.