Interiors in the Age of Enlightenment

Today we are highlighting and celebrating Bloomsbury’s recent publication of Interiors in the Age of Enlightenment: A Cultural History, edited by Stacey Sloboda. Sloboda’s thoughtful editorship has produced a volume that addresses nearly every topic and theme which with Home Subjects concerns itself, offering a holistic assessement of the aesethetics and cultural significance of all kinds of interiors in the eighteenth century. Noémie Étienne writes about the materials and surfaces that made up eighteenth-century interiors, from lacquered woods to porcelain objets d’art to wallpapers swathed with landscape, while Conor Lucey discusses the designers, architects, and merchants who worked together with patrons and consumers to assemble them. Mimi Hellman and Laurel Peterson respectively explore the visual and cultural politics of private and public interiors. Vanessa Alayrac-Fielding writes about themes of exoticism and globalism in interiors and their design while Michael Yonan considers the roles of gender and sexuality in their decoration, use, and cultural coding. Finally Melinda McCurdy and Karen Lipsedge survey the landscape of visual and written representations of interiors in the eighteenth century; such representations are important not only for what they can tell us about how people thought about interior spaces in this period, but also because they are one of our richest sources of evidence for interiors of this period. As such, they must be considered carefully and not interpreted as straightforward snapshots of the past. Please follow the links above to find previous Home Subjects posts by a number of these authors.

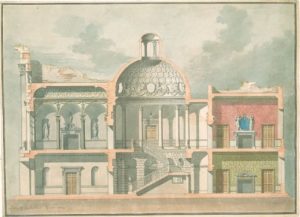

Sir William Chambers, Design for York House, Pall Mall, London, for the Duke of York, showing the proposed interior decoration, London, 1759. Royal Institute of British Architects Ref. No. RIBA3083-37

The contributions outlined above together weave a rich tapestry describing the parameters of the ‘interior’ in the long eighteenth century from the perspectives of design, technology, politics, culture and social practice. In the remainder of this post, I will provide a short preview of my own contribution to the collection, a chapter titled “Beauty,” which considers the evolving aesthetic character of interiors from the late seventeenth through the early nineteenth centuries to illuminate how aesthetics were inflected by all of the themes outlined above. A conventional approach familiar from textbooks might begin with Baroque and continue through Rococo and Neoclassicism before disintegrating into the ‘Regency’, a style defined by a cluster of elusive characteristics shaped by global influences to a notable degree. Instead, “Beauty” is divided into five general categories discussing a series of cultural aesthetic concepts, providing a framework to trace the most important long-term trends that shaped interiors over the course of the ‘Enlightenment’ period. ‘Magnificence’, ‘Artifice’, ‘Taste’, ‘Historicism’, and ‘Comfort’ are the keywords we chose to guide the reader through the history of interiors in the eighteenth century. These terms permit us to think about the complexity of style while avoiding falling back into a recounting of a succession of ‘styles.’

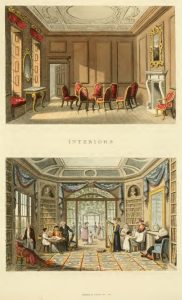

Humphry Repton, “The Ancient Cedar Parlour and the Modern Living Room” from Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London, 1816), photo courtesy of The Internet Archive.

After discussing a series of wide-ranging examples of the above keywords, from Versailles and Blenheim Palace to the building of Rio de Janeiro after the model of a European capital to Oak Hill near Boston, the chapter ends with a discussion of the theories of English landscape architect Humphry Repton who wrote about the decoration of interiors in Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening in 1816. During the second half of the eighteenth century, writers from William Hogarth and J.J. Rousseau increasingly sought to promote a view of human life that embraced the variability and ‘picturesque’ qualities of the natural world, moving away from the earlier impulse to control and suppress its wildness and unpredictablity. As a designer associated mainly with exteriors and landscapes, Repton sought to suggest how interior and exterior were intertwined. Repton writes, ‘of all the improvements in modern luxury, whether belonging to the Architect’s or Landscape Gardener’s department, none is more delightful than the connection of living-rooms with a green-house or conservatory.’ He gives a number of reasons, but amongst the most important is the introduction of natural light into the interior from multiple angles, which he asserts is critical for contributing to the “comfort and cheerfulness of a room.” The short chapter is accompanied by an illustration depicting the difference between the “Ancient” parlour and the “Modern” living room; where the old-fashioned parlour offers “silent gloom”–indeed the room is shown completely empty, only a circle of abandoned chairs enlivens the space–the living room, lit from one end by a capacious glass conservatory and from the side by French windows reflected in a mirror opposite, is full of company reading, socializing and playing music, the animation of the social interactions within acting in concert with the natural world without.

Repton’s image, though intended in part to illustrate a specific point about the importance of giving serious consideration to the sources of lighting in interiors, also alludes to a number of contemporary ideas and assumptions about interiors that had developed over the course of the century discussed in the chapter and, for that matter, in the collection as a whole. The “Ancient” parlour is not only dark, but more formal, part of a set of rooms built enfilade in a mode that served the social structures in place at the beginning of the previous century. The “Modern” room is filled with light, but uses the placement of furniture, the provision of multple points of entry and exit, and the interpenetration with the natural world outside to suggest a society that now welcomed ideas about comfort, relaxation, and the implication that these were more ‘natural’ ways to conduct oneself and live. Taking the long view of the evolution of concepts like ‘Magnificence’, ‘Taste’ and ‘Comfort’ demonstrates how such concepts were filtered through images like Repton’s to readers who wanted to understand for themselves how to make their own living rooms ‘modern’.