Making Room for Furniture

When I was in graduate school, I registered for the seminar “American Furniture” with Edward S. Cooke Jr., taught in the Furniture Study Center of Yale University Art Gallery. As a student whose undergraduate education had focused on painting and photography, I was excited to delve into a new area of art history. Maybe we would look at the representations of furniture in painting and photography? Imagine my surprise when I was surrounded by tallboys and side chairs and handed wood chip samples. I still remember the confusion I felt as I tried to recall the distinct sheen of tulip and the delicate grain of rosewood. The very materiality of the objects confounded me. From that moment, I have endeavored to practice a more integrated art history and make room for furniture history.

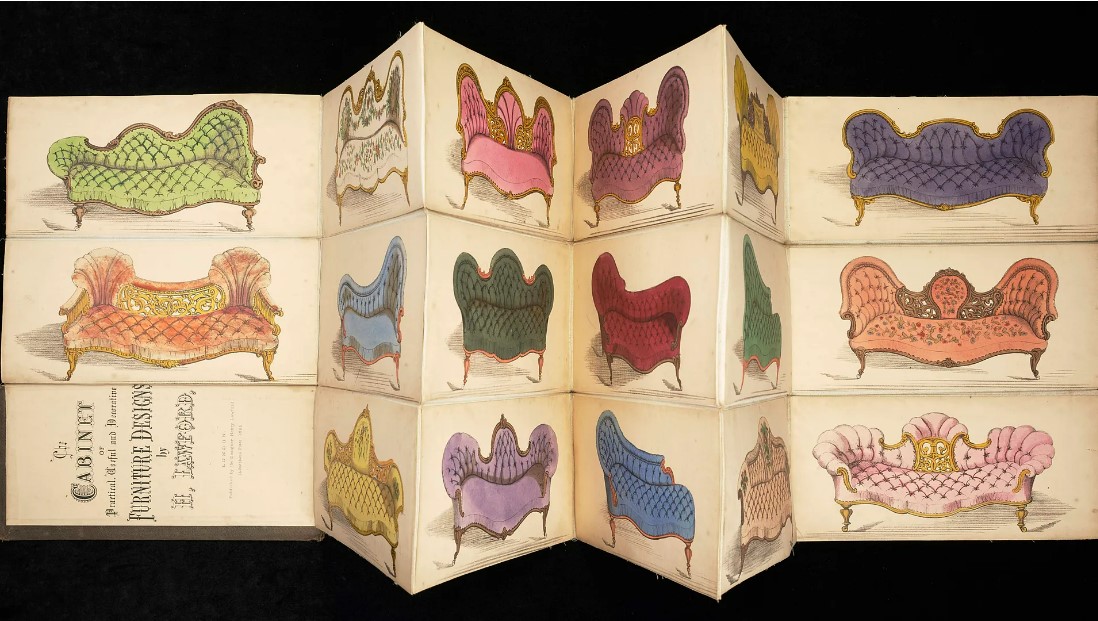

The Cabinet of Practical, Useful and Decorative Furniture Designs, a color-lithographed fold-out catalogue of sofa designs by Henry Lawford, 1855. The John Evan Bedford Library of Furniture History, University of Leeds

Thankfully, there are a number of upcoming events that focus on furniture, and its place in the decorative arts, as way to think through collecting and display. Readers who might want to explore these themes further can look forward to the upcoming What is Furniture History? conference at the University of Leeds.

The symposium program will include facilitated tours at Temple Newsam (part of Leeds Museums & Galleries) to explore the world class furniture collections at the house. The deadline for submission for proposals (c.200 words) is coming up on Monday April 15. Proposals can be sent to Mark Westgarth at [email protected]. The event also includes an opportunity to learn more about the resources at the university for the study of furniture history, especially the library of John Bedford, now housed in Brotherton Research Centre at the University of Leeds library. An exhibition of some of the highlights of his collection Part of the Furniture: The Library of John Bedford is on view until 21 December 2024.

Furniture will likely play a central role in the discussion generated by the upcoming 3-day conference The Commerce and Circulation of Decorative Art, 1792-1914: Auctions, Dealers, Collectors, and Museums, to be held in Lyon, France, beginning on 25 September 2024. As the call for papers stakes out the expansive approach to this topic:

This conference will focus on the commerce and global circulation of the decorative arts in order to open new perspectives and approaches that will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the art market. ‘Decorative arts’ are taken to include: furniture, metalwork, clocks, silverware, ceramics and glass, enamels, small sculpture, hardstone, ivories, jewellery, textiles, tapestries, and boiseries, from Ming dynasty porcelain, Mamluk glass, and Augsburg Kunstkammer objects to Boulle furniture and Thomire bronzes, not to mention the contemporary Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau movements.

This event is part of a wider project on the market for decorative arts in the long nineteenth century spearheaded by scholars at Lyon 2 Université. Since the call for proposals ended on 4 March 2024, we are hopeful that the program will be available soon.

Both of these events treat the market as a necessary part of the life of the decorative art, a condition that is not always at the forefront of the study of fine art. It is fascinating to note that they are also occurring at a moment when art museums, at least in the United States, are reconsidering how they display furniture, especially in the context of period rooms. Recently, the Brooklyn Museum of Art noted that it was selling off four period rooms and more than 200 examples of historical furnishings to “refine” the presentation of their collection and make room for new displays in Indigenous Arts, Contemporary Art, and Art of the Americas. As museum director Anne Pasternak noted, “Deaccessioning allows curators to refine and focus the collection, ensuring that we continue to display work that resonates and tells meaningful stories for our visitors.” The works were auctioned at Brunk in Asheville, North Carolina on March 20. It is a bit jarring to see the catalog listing for the Abraham Harrison House, installed at the Brooklyn Museum until 2004, as “architectural elements, stone and wood.” The description of the interior according to materials (stone, wood) reminded me of my first day in American Furniture. Once you have the materials in mind, the objects and environment open themselves up to a richly varied range of interpretations and meanings. (And purchases must have realized as much. The Abraham Harrison House lot far exceeded its estimate of $2000-3000 with a hammer price of $60,000).

As the date range of the Lyon event suggests, many period rooms entered museums collections in the United States in the early twentieth century. Many of the works in the Brooklyn Museum of Art sale group were donated by Luke Vincent Lockwood (1872-1951), a lawyer and author of Colonial Furniture in American (1901). As Philippe de Montebello noted in Period Rooms at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1996), “the tradition of period rooms in America is usually associated with institutions that thrived during the 1920s,” many of which were built around the idea of the period room: Winterthur, Colonial Williamsburg, and even the Metropolitan Museum of Art. These presentations of a unified interior gave visitors a window into the past even as they opened up institutions to criticism in terms of how they displayed that past, especially when original furnishings did not survive.

Drawing Room from Lansdowne House. Designed by Robert Adam, Scottish, 1728 – 1792, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Take, for example, the drawing room at Lansdowne House, an “archetypal” work by the Scottish architect and designer Robert Adam originally situated on the ground floor of the London house that he designed for the third Earl of Bute in the 1760s. The sumptuous Pompeiian environment, with painted decoration by Giovanni Battista Cipriani and Antonio Zucchi, and gilding by Joseph Perfetti, came about when the house was acquired by William Petty Fitzmaurice, second Earl of Shelbourne and later first Marquess of Landsowne. As the Philadelphia Museum of Art acknowledges, “Although the paintings and furniture currently on view did not furnish the room when it was in London, they were selected from the museum’s collection to reflect works popular at that time, as many British elites collected contemporary European paintings, favoring landscapes and scenes from mythology and the Bible, as well as antiquities like the ancient Greek pottery seen on the mantelpiece.” The recent appreciation of period rooms by Kelly Faircloth in dwell emphasizes the immersive quality of the spaces. As she notes, the PMA recently replaced the historical carpet in the Lansdowne House room with a modern facsimile “so that people can actually walk in and experience the room, as opposed to just walking up to a guard rail and peering in.”

Today, the museum provides multiple points of access to help visitors understand the complex historical layering in the interior, such as this video tour. At the same time, social media seems to have given these rooms new life, from “period room” boards on Pinterest to accounts such 18thcentury_life on Instagram.