Living with Modernist Heritage

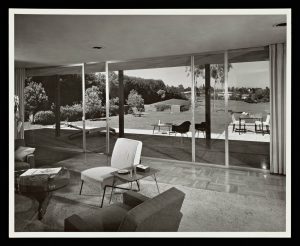

Interior of the Zimmerman House designed by Craig Ellwood, landscape design by Garrett Eckbo. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10); photo by Julius Shulman

We at Home Subjects are never immune to the allure of some internet gossip/outrage, so our interest was piqued by last week’s brouhaha over the news that Chris Pratt and Katherine Schwarzenegger had purchased and then demolished a notable mid-century dwelling known as the Zimmerman house designed by architect/designer Craig Ellwood (1922-1992). Although Ellwood was not a licensed architect, he is widely recognized for his design work marrying the aesthetic vision of figures like Mies van der Rohe to the California lifestyle. According to the LA Times, the Zimmerman house was one of his earlier designs, commissioned in 1949 and completed in 1950. The house was never designated as an historic or architectural landmark despite its status as a well-preserved domestic dwelling from this period; equally disappointing is the loss of the landscape garden envisioned for the house by widely-influential designer Garrett Eckbo (1910-2000). Both Zimmerman house and garden were razed in order to accommodate a 10,000sf new house, pool and accessory dwelling on the .83-acre lot. Matt Stromberg of Hyperallergic interviewed Adrian Fine, president and CEO of Los Angeles Conservancy for his piece on the incident, who said that “there are just too many significant buildings and not enough resources to pursue this designation for all applicable candidates.” Ellwood’s daughter, interviewed by the LA Times, expressed disappointment that the house was not given an appropriate send off, while recognizing that at some point, there are limits to what will ever be saved, especially in a city as rich in mid-century architecture as Los Angeles. Similarly Adriene Biondo wrote about the controversy for the Eichler Network, a site celebrating the work of Joseph Eichler, who popularized modernist chic through building planned communities at price points available to a much wider range of people. Biondo lamented that “at the same time as architectural homes are being marketed as high-end collectible art, others are being torn down to build new.” As Liz Waytkus of Docomomo US told Hyperallergic, “location and land value often trump architectural significance.” In Los Angeles and its suburbs, land is at a premium. While there is no shortage of high net-worth people looking to acquire dwellings with built-in prestige or glamour, there are at least as many who will value the site more highly than the buildings, however historically significant, already present.

Following Biondo’s implication that some houses are themselves raised to the status of “collectible art” suggests points of contact with our interests at Home Subjects. Our preoccupation is the relationship between houses and design and the objects, including furniture and artworks, that fill them, but often the houses themselves, whether English country estates or southern California ranch dwellings, are works of aesthetic significance in their own right. In this case, the loss of lived-in examples of modernist architecture further diminishes historians’ ability to fully understand the design relationships that animated such interiors, not to mention the patterns of daily life that are enabled and directed by the spaces within which they unfold. However, rather than further lament the demolition of one such example, this is an opportunity to bring to our readers’ attention some of the outstanding examples of mid-century dwellings that have been maintained in a state of preservation close to their original condition.

Edwin Heathcote has been writing an ongoing series celebrating the world’s best house museums for the Financial Times; modernist buildings form a robust subset of this group. Amongst the museums Heathcote recognizes are the Musée Zadkine in Paris, the home-workshop of Belorusian artist Ossip Zadkine; Mies van der Rohe’s Villa Tugendhat in Brno; Casa de Vidro near São Paulo, designed by Italian architect Lina Bo Bardi; 2 Willow Road in Hampstead, London, built by architect Ernő Goldfinger as a family residence where he lived until 1987; and Schindler House in West Hollywood, Ca. Not on Heathcote’s list but highly recommended by a friend of Home Subjects is Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht, which was occupied by its original patron, Truus Schröder-Schräder, until her death in 1985 aged 95.

Guest bedroom in the Brick House designed by Philip Johnson, 1949, remodelled 1953. Wall sculpture: Ibram Lassaw, Clouds of Magellan, 1953. Photography by Julius Shulman and Juergen Nogai, published in The New York Times April 13, 2024

Recently however, one house of particular significance to the history of American architecture was featured in the New York Times as its 75th anniversary arrived. Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Ct. a stalwart of undergraduate architecture history surveys, is a minimalist, open-plan glass box surrounded by a landscape that appears to be its occupants’ only recourse to privacy. Less widely known has been the adjacent Brick House, intended to be used in concert with the Glass House, but that has changed with the recent re-opening of the Brick House to the public after the completion of a long-needed restoration. The Brick House is the Glass House’s double, providing privacy, warmth and intimacy where its sibling was a stage for the self to put itself on display. Christopher Hawthorne’s article for the Times is illustrated with beautiful photographs of this building, which because of its poor state of repair had been mostly obscured from public view for some time. What the Times also fascinatingly explores is how the recovery, refurbishment and re-opening of the Brick House has enabled new interpretations of Johnson’s work. Mark Lamster, architecture critic for The Dallas Morning News, used the Glass House as a central metaphor in his 2018 biography of the architect. The house will be hosting a series of lectures and conversations exploring this history, including one coming up May 5 with historians Alice Friedman and Timothy Rohan that explores the house in terms of its “cultural significance” and place in “queer social history.” Scholars like Lamster have likewise begun to reconsider Johnson’s interest in Fascist politics. As the Times disconcertingly describes, Johnson’s own writings affirmed that elements of the Glass House were inspired by things personally witnessed during a visit to Poland in 1939. As we have written repeatedly in Home Subjects, it is only through a holistic interpretation of architecture, furniture, use and their expression through aesthetics AND politics that we can truly gain a full appreciation of the house as a cultural touchstone.