Unveiling the Grandeur: The Gallery at Cleveland House

We’ve had a busy summer here at Home Subjects, so we took a bit of a hiatus. But I’m excited to say that we are back with big news: the publication of Anne’s book! She had previously written about aspects of her research for Home Subjects in 2016 and As her friend and co-editor, I couldn’t be more proud of Anne, so I wanted to take this opportunity to celebrate her scholarly achievement. –MO’N

William Bond (engr.) after J.C. Smith, The New Gallery at Cleveland House in John Britton, Catalogue Raisonné of the Pictures belonging to the most honourable The Marquis of Stafford, in the Gallery of Cleveland House (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1808). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The Gallery at Cleveland House: Displaying Art and Society in Late Georgian London takes readers a captivating journey into one of Regency London’s most prestigious art collections. This meticulously researched work not only illuminates the story of a remarkable private gallery but also provides profound insights into the social, cultural, and artistic landscape of early 19th-century Britain.

At the heart of Richter’s study is Cleveland House, the London residence of the Marquess of Stafford, which housed an internationally renowned art collection. Through her expert analysis, Richter reveals how this aristocratic family skillfully navigated the complex waters of society and politics through the strategic display of their artistic treasures. The book goes far beyond a simple catalog of artworks, delving deep into the multifaceted roles that such a collection played in the life of the elite and the broader cultural milieu of the time. One of the most striking aspects of Richter’s work is her innovative methodological approach. By weaving together diverse threads of inquiry – including the history of collecting, museum studies, material culture, and architectural history – she creates a rich tapestry that brings the Gallery at Cleveland House vividly to life. Fans of period dramas like Bridgerton will find much to savor in Richter’s evocative descriptions of the social world surrounding the gallery.

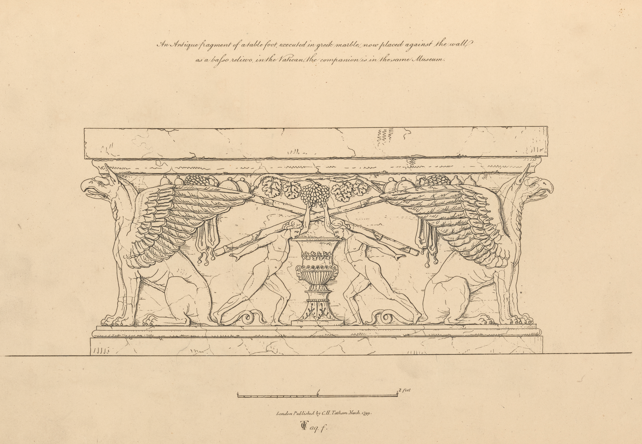

Charles Heathcote Tatham, “Antique fragment of a table foot, executed in greek marble” from Etchings, representing the best examples of ancient ornamental architecture (London: Printed for the author, 1799). Avery Classics, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

Perhaps most importantly, the book offers valuable insights into the historical roots of how we view and understand art today. By exploring the genesis of the “national collection” concept and examining early display practices, Richter invites readers to reflect on the evolving relationship between art, society, and national identity. As we navigate our own era of evolving museum practices and debates about the role of art in society, Richter’s book provides a crucial historical perspective. It reminds us that the way we encounter art is deeply shaped by social, political, and cultural forces – a reality as true in the glittering salons of Regency London as it is in the diverse array of exhibition spaces we frequent today.

One aspect of this discussion that I find particularly fascinating is Anne’s attention to gallery furnishings, an interest she wrote about in a Home Subjects post in 2022. Her keen eye has examined not only the works of art on display but the interior that enveloped them. For example, she uses the tables shown in J. C. Smith’s view of the New Gallery at Cleveland House as an example of the accretive nature of architectural and design history. She links them to the influence of ancient Greece and Rome as allied to family history and social function through Charles Heathcote Tatham’s representation of a similar table in his primer on ancient ornamental architecture, and examples such as the Marsh & Tatham table currently in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. As she notes, this “private” home had an extraordinarily public profile. Between 1807 and 1818, the gallery’s interiors were recorded in detail in an extraordinary set of plans made by the engraver P.W. Tomkins, which depicted all thirteen of the rooms, both large and small, that made up the gallery at Cleveland House. As she notes, there is no comparable record of the interior of any private house in Britain in the nineteenth century. Tomkins’ images mark an important step in the development of a visual language of upper-class domesticity. They permit each room to be represented with its idiosyncrasies intact, “every space constituting a stop on a journey through the gallery and offering a different set of pictures, references, and associations to the viewer, inviting him or her to imagine the space in use, animating it with the practices of private life that ostensibly took place within.” Mirrors reflected light, furniture provided seating, and windows offered a view into the park beyond.

Marsh & Tatham, console table, c. 1805-1811, London, England. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, The Rienzi Collection, gift of Mr and Mrs Harris Masterson III

The Gallery at Cleveland House: Displaying Art and Society in Late Georgian London is more than just a study of a single collection; it’s a window into a transformative moment in the history of art and society. For anyone fascinated by the power of art to shape our world, this book offers a compelling exploration of a pivotal chapter in that ongoing story.