The Art of WFH at the Brontë Parsonage

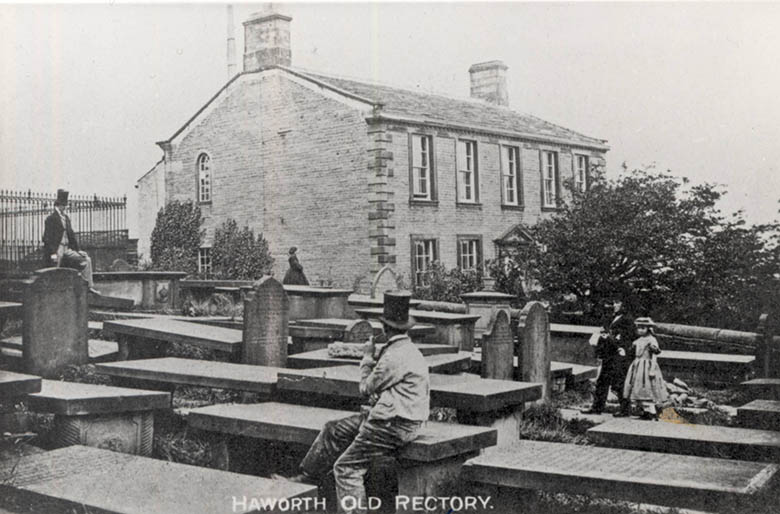

Haworth Parsonage and cemetery, pre-Wade Extension c.1878 by English Photographer, (19th century); © Bronte Parsonage Museum, Haworth, Yorkshire, U.K..

In the windswept Yorkshire moors stands a modest parsonage in Haworth. This unassuming home was where the Brontë sisters—Charlotte, Emily, and Anne—created some of English literature’s most enduring works, and it now serves as the Brontë Parsonage Museum. In October 2022, chef and journalist Lauren Joseph reflected on the parsonage in the Wall Street Journal as she sought to redesign her own writing quarters in London. She concluded that the decor was “nice” and “serious,” a space that minimized decorative distractions. There’s something poignant about revisiting how the Brontës navigated their creative and professional lives from home, long before “working from home” entered our vocabulary. As we know here at Home Subjects, our homes shape our thinking in subtle ways, from the art on our walls to our choice of Zoom background when WFH. As Joseph noted, a visit to the Brontës parsonage reminds us that these influences can enrich our professional output. As she discussed the “asceticism” of the interior, however, I began to wonder about the art on the walls. The Brontë Parsonage Museum is managed by the Brontë Society, founded in 1893 to promote interest in the Brontë family and their works. They opened a permanent home for items belonging to the Brontës as a museum in 1895 on Haworth Main Street. The Haworth Parsonage was bought by Sir James Roberts and gifted to the Brontë Society in 1928. In that year, it opened as the Brontë Parsonage Museum. The museum is dedicated to preserving and promoting the lives and legacy of the family, particularly through the environments and objects that shaped their life and work. After Patrick Brontë’s death in 1861, the contents of the Brontë family home in the Parsonage dispersed so while the museum strives for historical accuracy in the interiors, they acknowledge that some objects are not original to the house. Nevertheless, my visit last summer prompted me to ponder the role that visual art might have played in the decoration of the interior and the notion of the home as a creative hub for the Brontë siblings.

Their father, Patrick Brontë, served as the local clergyman, making the parsonage both a family home and a professional base. The geographical isolation of Haworth encouraged the Brontë siblings to create a vibrant intellectual community within their home. The sisters maintained rigid writing schedules while juggling household duties, caring for their ailing father, and managing their brother Bramwell’s declining health. The sisters wrote at a small dining table in the shared family room, while their father maintained his own study. Charlotte wrote in her letters about the challenge of protecting creative time while meeting family obligations, and sisters developed systems that support working from home. Emily was known to continue kneading bread dough while working through narrative problems, an early version of the “walking meeting.” For the Brontës, home was not just where they worked but a wellspring of inspiration. The parsonage’s windows framed views of the moors that figured prominently in their writing. Emily’s “Wuthering Heights” captures the wild, untamed landscape just beyond their door, while the parsonage itself—with its narrow staircases and shadowy corners—echoes through Charlotte’s descriptions of Thornfield Hall in “Jane Eyre.”

Mr. Brontë’s Study with prints after paintings by John Martin © 2024 Credit :Bevan Cockerill ©The Brontë Society

Patrick Brontë collected a modest but significant array of prints and engravings that hung in the Haworth Parsonage, including works by John Martin and Benjamin West. His collection featured primarily religious and historical subjects, landscapes, and reproductions of notable paintings from the Royal Academy exhibitions. Though not an extensive or expensive collection, these accessible art reproductions served as important teaching tools and artistic references for Branwell and his sisters. They were a primary source of art education for Bramwell, as he would meticulously copy them to develop his technique in the absence of formal training. Among the most profound influences on the Brontës’ imaginative landscapes were the mezzotint prints by artist John Martin. The parsonage walls featured several of Martin’s dramatic works, including “Belshazzar’s Feast,” “Joshua Commands the Sun to Stand Still,” and “The Deluge.” These monumental and apocalyptic scenes depicting vast architectural landscapes and biblical catastrophes inspired the young writers.

Charlotte, at just 13, described magical cities with “marble pillars” and “mighty towers” in her early writings about Glass Town, the detailed imaginary world created by the siblings alongside their brother Bramwell Brontë. Her imagery seems to be influenced by Martin’s grandiose architectural visions. These prints, with their startling clarity and sinister eeriness, provided more than decoration; they opened windows to alternate worlds that fed the sisters’ imaginations. As Christine Alexander has noted, the Brontë children both copied his images in paint and transposed them into “print” in their tiny handsewn magazines. For Alexander, Martin is an important touchstone in Charlotte BBrontës The monochromatic mezzotints, lacking color but compensating with chiaroscuro and detail, created an ominous quality that likely shaped the Gothic elements in the Brontës’ fiction. Charlotte later saw Martin’s “The Last Man” during her 1850 visit to London, describing it in a letter to her father as “a grand, wonderful picture.” For Alexander, however, Martin is an important touchstone in Charlotte Brontë’s own development as an artist, and her initial enthusiasm for his work is gradually replaced by a distrust of his “illusive promises of grandeur.”

In addition, we can find ways in which the theme of art in the home is threaded through Charlotte Brontë’s novels. As Mike Klotz has discussed, references to visual art work seamlessly with discussion of interior decoration in Jane Eyre and Villette. The portraits in St. John Rivers’ home function as extensions of his character in Jane Eyre—just as his outdated, immaculately preserved furniture suggests his rigid, unchanging nature, the “dusky pictures” parallel his static personality. When Jane describes St. John as “sitting as still as one of the dusky pictures,” the artwork becomes both decorative element and character metaphor. Similarly, in Villette, Lucy Snowe’s recognizes the handscreens (like this example from the V&A, intended to shield the face from the warmth of a fire) with “elaborate pencil-drawings” she created as a child. They serve as both ornamental elements within Mrs. Bretton’s parlor and tangible connections to Lucy’s past self. As Klotz’s argues, “the furnishing of rooms and the narration of experience” are intrinsically connected in these novels. The Brontë Parsonage Museum is a testament to what can be created from home. While visitors walk through these rooms they experience what the late Victorian decorators Agnes and Rhode Garrett called “the impress of the home” that must “come from within”—one that balanced creative freedom and professional output with domestic life.